International promissory note

July 24, 2017

“Imagine getting your debts paid off, including student loans, back child support debt and get your home free and clear with the Little Promissory Note,” the website promises, “LPN Money that you don’t have to pay back once it is processed.” A YouTube video advertising this “Little Promissory Note” promises that it “is the same as a dollar bill that can pay off all types of debts.”

The Little Promissory note sounds pretty powerful, right? Pay off student debts, get out from underneath a suffocating mortgage? It sounds almost too good to be true.

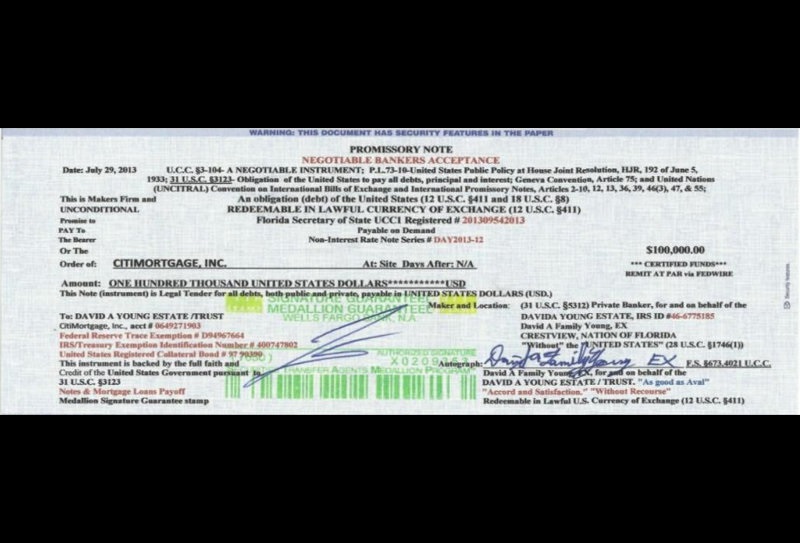

Indeed, it is exactly too good to be true. The Little Promissory Note is the cozily-named creation of a Texas sovereign citizen, David Allen Young, and is an example of a common tactic employed by this anti-government extremist movement: creating fictitious financial instruments.

A financial instrument is a document such as a check or money order meant to serve in lieu of cash money in financial transactions. A fictitious financial instrument is one that is simply made up out of whole cloth, with no actual value. Sovereign citizens use these instruments to scam everybody from the government to automobile dealers to desperate homeowners.

The sovereign citizen movement is an extreme anti-government movement nearly fifty years old whose adherents believe that a malign conspiracy took over the legitimate government of the United States and replaced it with an illegitimate, tyrannical government. People who discover this secret can take certain steps that allow them to “divorce” themselves from the government, following which they claim it has no authority or jurisdiction over them and they can ignore its laws and regulations.

The movement’s interest in fictitious financial instruments dates all the way back to the early 1980s. One pioneer was Tupper Saussy, a tax protester and songwriter who created check-like instruments he called Public Money Office Certificates. Saussy’s argument was based on the sovereign belief that valid “money” consists only of gold or silver and, since the U.S. is no longer on the gold standard, there is really no such thing as “money.” Saussy told people they should pay bills such as utilities with his certificates, which promised that the user would pay with money “as soon as the substance of money was determined.” Until then, utilities could just keep the certificates.

Saussy’s certificates were designed primarily as a protest, but other 1980s sovereign citizens were more ambitious. Some sought to pay taxes with bogus “promissory notes,” while others tried to buy homes or properties with bogus “bills of exchange.” One couple tried to fight foreclosure on their farm by sending the bank a bogus “sight draft” for over $100,000. Among the most ruthless were several sovereigns who deliberately targeted desperate farmers in the Midwest during the 1980s farm crisis, selling them fictitious sight drafts and “fractional reserve notes” that they promised farmers could use to pay off their debts and save their farms. The notes were all worthless, of course, and only made the plight of the farmers worse.

Sovereign use of such bogus instruments continued in the 1990s but became even more popular after 1999, when one sovereign guru, Roger Elvick, who spent much of the 1990s in prison for using bogus instruments to scam farmers in the 1980s, released a new version of his scheme, which he called “redemption.” Other sovereign gurus began promoting it as well and it spread like wildfire through the entire movement. Like earlier schemes, it was based on the notion that money had no value since it was not backed by gold. Through a complicated process, people could create “bills of exchange” that they could be used to pay off debts (according to some sovereigns) or to purchase almost anything (according to others).

A flood of fictitious financial instruments of various kinds followed, even though passing such instruments is now a federal crime. A few recent incidents illustrate their use:

• Portland, Oregon, April 2017. A federal jury convicted prominent sovereign citizen guru Winston Shrout of, among other things, 13 counts of issuing fictitious financial instruments to banks and the government—bogus “bills of exchange” with a purported face value of over $100 trillion. He faces sentencing in early August.

• Honolulu, Hawaii, April 2017. Dennis Alexio, a former kickboxing champion, received a 15-year prison sentence after being convicted of a variety of offenses, including using bogus financial instruments, as the Justice Department put it, “to obtain property from multiple unsuspecting victims.”

• Hermosa Beach, California, April 2017. Tax protesters Sean and Melissa Morton were convicted of conspiracy, false claims and multiple counts of passing bogus financial instruments, typically using bogus “coupons” and “bonds” to pay off IRS debts.

• Minneapolis, Minnesota, December 2016. Chiropractor and sovereign citizen Donald Gibson was convicted of tax evasion and passing a fake financial instrument for a scheme in which Gibson failed to pay federal income taxes, used bogus warehouse banks to hide money, and giving bogus money orders and other financial instruments to the IRS, including one with a face value of $300 million.

Some sovereigns try to pass such instruments themselves, while others may charge people to learn how to create and use such instruments to pay off their debts, or sell such instruments directly to victims, promising that they can be used to pay off debts. Pitches that promise bogus promissory notes or bills of exchange can be used to pay off mortgages or prevent foreclosures have been particularly popular since the mortgage and foreclosure crisis that began in 2008. “Don’t wait until your home is already in foreclosure!” warns David Young in text accompanying one of his YouTube videos marketing his Little Promissory Note.

Young’s Little Promissory Note is a good example of a current fictitious financial instrument scheme. Back in 2008, Young ran a different sort of business, called Destinctive [sic] Realty, in which he promised to help save people money on their home purchases (“Save $5,000 to $55,000…guaranteed!”). At the same time, Young seems to have engaged in other real estate ventures in Florida.

But Young soon began having problems keeping up with his own mortgage, a plight that seems to have lured him into the sovereign citizen movement. By 2012, Young and his wife were filing pseudo-legal sovereign documents (such as a “Certificate of Default for Notary Protest”) in apparent attempts to protect their property—attempts rejected by the courts. From various court orders and filings, it appears that Young unsuccessfully tried to use “promissory notes” to pay off different mortgage companies, some as late as 2016.

By then, Young had already been marketing such notes to others, using a variety of websites and social media accounts. “All I can say for sure,” he asserted in one 2015 posting, “is that I paid off my Home Mortgage using an IPN [International Promissory Note] and I have the recorded proof.” He also offered a $100,000 “cash guarantee” to anyone who would find a law that his promissory notes were a fraud or scam (“I will personally give them $100,000 CASH in fiat Federal Reserve International Promissory Debt Notes that people perceive as money but is not real gold and silver coin money as in…the Constitution.”).

However, Young also asked prospective customers to sign a “confidentiality non-disclosure agreement” in which they would agree to pay $100,000 if they gave or sold his documents to anybody else and would also agree to hold him harmless “of any and all acts and deeds” and to give up any rights to civil litigation or court action.

Young’s services don’t seem to come cheap. One of his documents tells customers that “today your investment is just $4,000 onetime payment to pay off any debt under $300,000 with a $1,000 discount for the second or third promissory note.” Higher payments would allow higher amounts of debt to be satisfied, up to $50,000 to eliminate a $10 million debt. People could also pay to become a member of an entity created by Young, the Private Bankers National Banking Association, which would allow people to “become a private bank” in less than 30 days. According to Young, private banker members “are authorized to write and issue prepossessed PBNBA promissory notes to pay off all type of financial debts.” These notes, the PBNBA asserts, are accepted by Federal Reserve banks.

The history of such fictitious financial instruments should lead anybody who encounters such a pitch to be wary of any and all proffered promissory notes, whether “little” or not.