Free to Play? Hate, Harassment and Positive Social Experiences in Online Games.

Survey Report

Executive Summary

This report explores the social interactions and experiences of video game players across America and details their attitudes and behaviors in a rapidly growing social space. Globally, video games are a $152 billion industry. Fifty-three percent of the total population of the US and 64 percent of the online population of the US plays video games.1 Video games have functioned as social platforms over the past three decades, with players around the world interacting with one another while playing games online. As with other social platforms, these interactions can be both personally enriching as well as harmful.

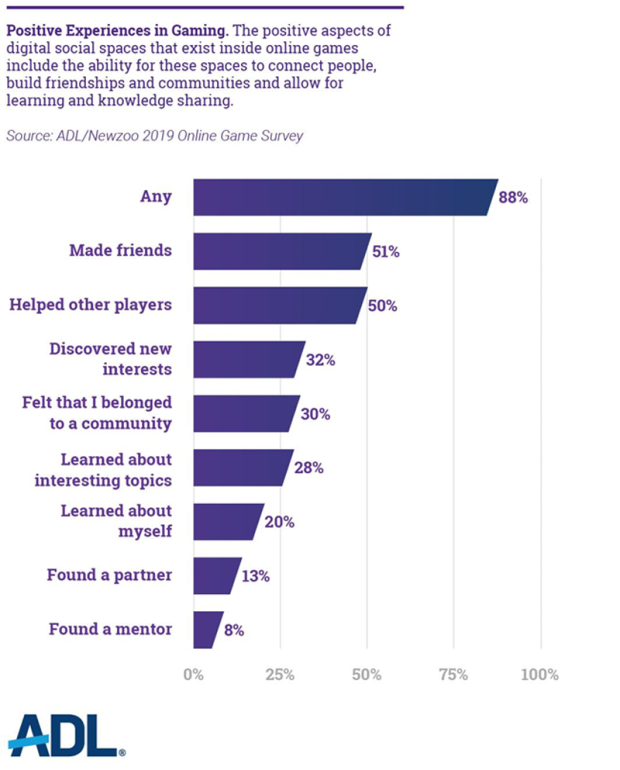

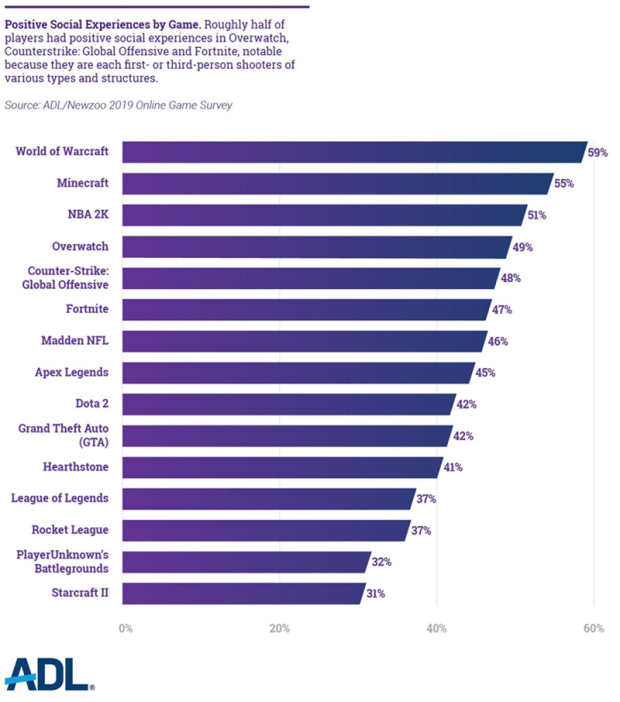

In this report we provide an analysis of key findings from a nationally representative survey designed by ADL in collaboration with Newzoo, a data analytics firm focusing on games and esports. The survey found that 88 percent of adults who play online multiplayer games in the US reported positive social experiences while playing games online. The most common experiences were making friends (51%) and helping other players (50%). The games in which players most reported positive social experiences were World of Warcraft (59%), Minecraft (55%), NBA 2k (51%), Overwatch (49%), Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (48%), and Fortnite (47%).

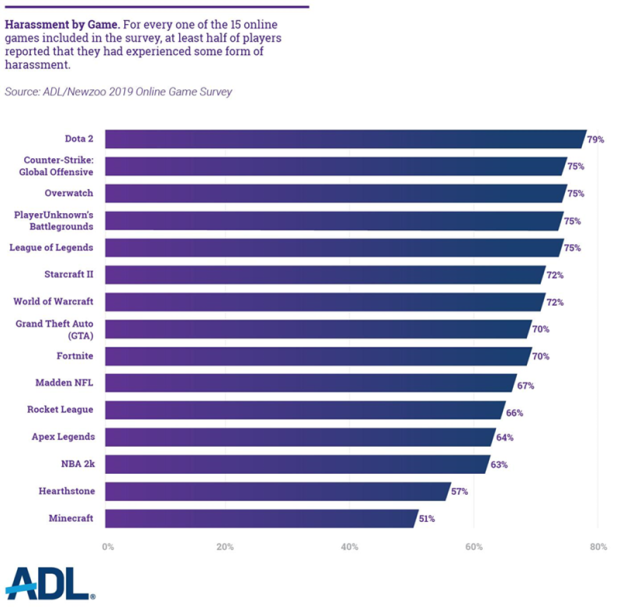

In spite of these findings, the survey also found that harassment is quite frequent. This should give the industry pause. Seventy-four percent of adults who play online multiplayer games in the US experience some form of harassment while playing games online. Sixty-five percent of players experience some form of severe harassment, including physical threats, stalking, and sustained harassment. Alarmingly, nearly a third of online multiplayer gamers (29%) have been doxed.2 The games in which the greatest proportion of players experience harassment are Defense of the Ancients 2 (DOTA 2) (79% of players of the game), Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (75%), Overwatch (75%), PlayerUnknown Battlegrounds (75%) and League of Legends (75%).

Fifty-three percent of online multiplayer gamers who experience harassment believe they were targeted because of their race/ethnicity, religion, ability, gender or sexual orientation. Thirty-eight percent of women and 35 percent of LGBTQ+ players reported harassment on the basis of their gender and sexual orientation, respectively. Approximately a quarter to a third of players who are black or African American (31%), Hispanic/Latinx (24%) and Asian-American (23%) experienced harassment because of their race or ethnicity in an online multiplayer game. Online multiplayer gamers were also targeted because of their religion: 19 percent of Jews and Muslims also reported being harassed.3

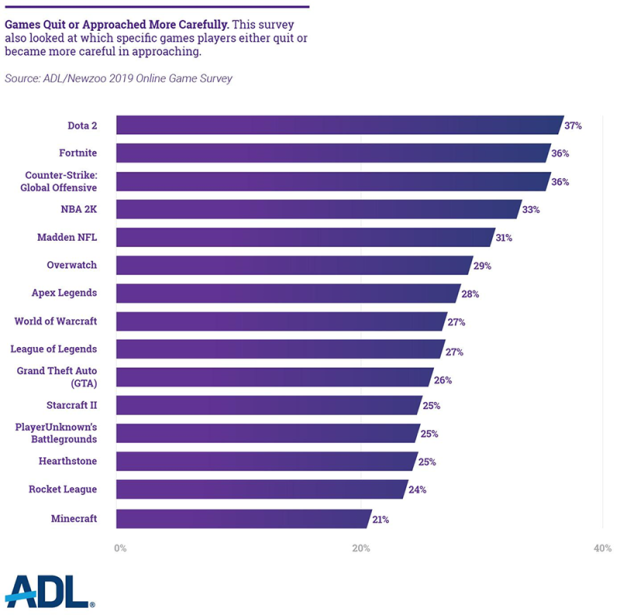

Twenty-three percent of online multiplayer gamers who have been harassed avoid certain games due to a game’s reputation for having a hostile environment while 19 percent have stopped playing certain games altogether as a result of in-game harassment, as other research has suggested.4 The games that most players either become more careful playing or stopped playing altogether as a result of harassment are Dota 2 (37%), followed by Fortnite (36%), Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (36%), NBA 2K (33%), Madden NFL (31%), Overwatch (29%), Apex Legends (28%), World of Warcraft (27%), and League of Legends (27%). Perhaps most notably, only 27 percent of online multiplayer gamers reported that harassment had not impacted their game experience at all, meaning that fully 73 percent of players had their online multiplayer game experience shaped by harassment in some way.

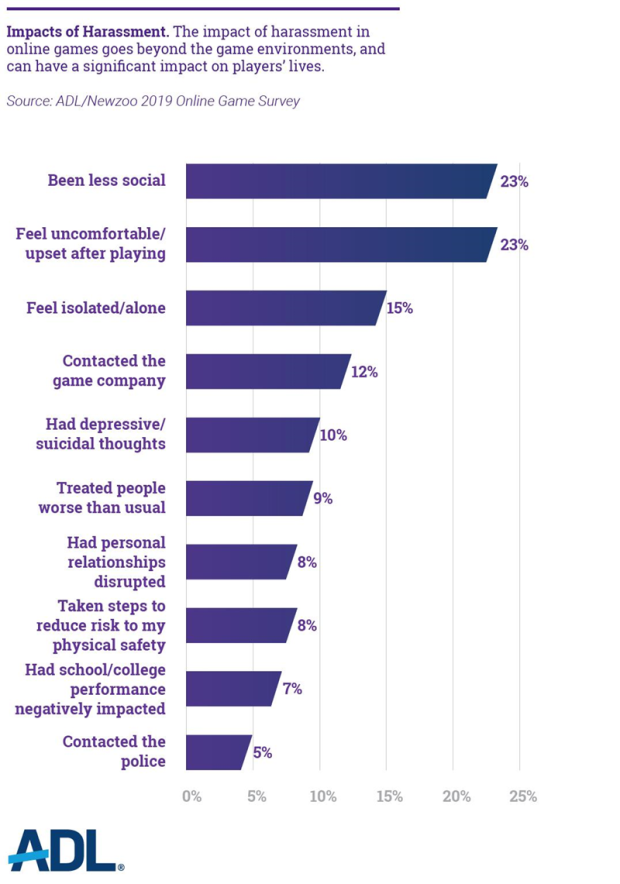

The impact of harassment in online multiplayer games goes beyond game environments as well: 23 percent of harassed players become less social and 15 percent feel isolated as a result of in-game harassment. One in ten players has depressive or suicidal thoughts as a result of harassment in online multiplayer games, and nearly one in ten takes steps to reduce the threat to their physical safety (8%). To seek recourse for online harassment, 12 percent of online multiplayer gamers contact a game company and 5 percent call the police.

In addition to harassment, the study also explores players’ exposure to controversial topics, such as extremism and disinformation in online game environments. Alarmingly, nearly a quarter of players (23%) are exposed to discussions about white supremacist ideology and almost one in ten (9%) are exposed to discussions about Holocaust denial in online multiplayer games.

The survey also measured players’ attitudes towards efforts to make online multiplayer games safe and more inclusive spaces for players. A majority of online multiplayer gamers (62%) agree that companies should do more to make online multiplayer games safer and more inclusive for players, and over half (55%) agree that these games should have technology that allows for content moderation of in-game voice chat.

We see opportunities for many different stakeholders to take action and do more to address harassment in online games:

- Games Industry: Game developers and publishers need to take a more holistic approach towards reducing hate and harassment in online games. This includes developing sophisticated tools for content moderation that include voice-chat; comprehensive and inclusive policies and enforcement around hate and harassment that mirror and improve upon the known best practices of traditional social media; and game ratings systems that consider the amount of harassment in specific games, among other improvements. The games industry should also reach out to collaborate with civil society, to educate civil society about the unique challenges of their community and take advantage of civil society’s expertise.

- Civil Society: Just as in recent years much of civil society has expanded their work to include the impact of traditional social media on their issues and communities, so too should civil society use their resources, expertise and platforms to address the impact of games as digital spaces. To aid in this, civil society should engage with and support scholars and practitioners who have been and continue to do crucial research and practice to help fight hate, bias and harassment in games.

- Government: Federal and state governments should strengthen laws that protect targets of online hate and harassment, whether on social media or in online games. Governments should also, as they do with social media companies, push for increased transparency and accountability from game companies around online hate and harassment.

We believe this report provides insight into the power of video games to enrich lives and also a better understanding of ways the game industry can improve.

Introduction

In March 2019, the CEO of Epic Games--creators of Fortnite, one of the most popular games in the world (especially in Western countries) --spoke about the future of the game industry:

“We feel the game industry is changing in some major ways. Fortnite is a harbinger of things to come. It’s a massive number of people all playing together, interacting together, not just playing but socializing. In many ways Fortnite is like a social network. People are not just in the game with strangers, they’re playing with friends and using ‘Fortnite’ as a foundation to communicate. We feel now is the time and we have very large ambitions.”5

The idea of online games as social platforms is not new. Some of the earliest virtual communities, going back to 1978 6, were MUDs or “Multi-User Dungeons” where users played together inside text-based fantasy adventure games on university servers. MUDs developed over time to adapt to the growing internet, including both this kind of fantasy adventure game experience, but also more general social interaction. In the early 1990s, MUDs were even being called “the first examples of social virtual realities.7 Over time, graphics were introduced, first with the game Habitat in 19858 and notably with Neverwinter Nights launching online inside AOL in 1991. Neverwinter Nights became a blockbuster due in large part to its social nature, with players organizing their own in-game summer festivals, trivia nights, and competitions, and those with good reputations being promoted to a version of a community moderator.9 As access to the internet expanded, this model did as well with the noted successes of stand-alone massively multiplayer online games such as Everquest and Ultima Online in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2006, noted game scholars Constance Steinkuehler and Dmitri Williams examined the rapidly expanding ecosystem of massively multiplayer online games10 (MMOs) like Everquest and Ultima as spaces for social interaction. They found that:

“By providing spaces for social interaction and relationships beyond the workplace and home, MMOs have the capacity to function as one form of a new “third place” for informal sociability much like the pubs, coffee shops, and other hangouts of old. Moreover, participation in such virtual “third places” appears particularly well suited to the formation of bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000), social relationships that, while not providing deep emotional support per se, typically function to expose the individual to a diversity of worldviews.”

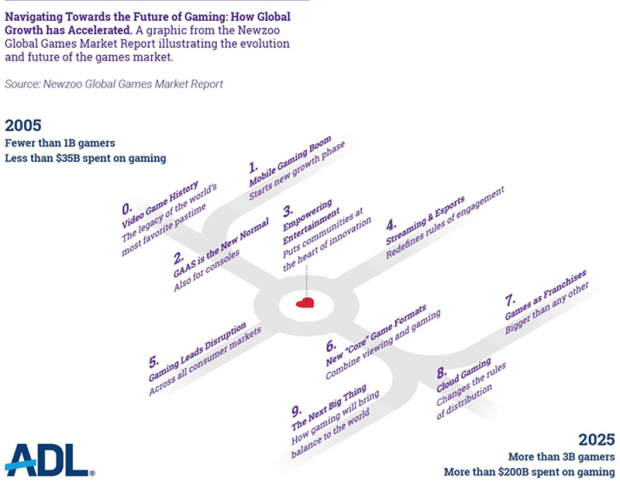

Since then, the games industry and online games have experienced explosive growth, becoming a roughly $150 billion industry today. Over two billion people play games globally and projections have predicted the industry growing to over $200 billion in revenue with three billion players globally by 2022.11 This has been driven in large part by the growth of online games, online communities and publications around games and social media platforms designed specifically for the game community (e.g., Twitch and Discord).12 In the first quarter of 2019 alone, prominent traditional tech and social media companies have announced major initiatives focused on online gaming communities such as Google’s Stadia initiative and Facebook’s adding a gaming tab to the core functionality of its platform.13

According to the Entertainment Software Association, 65 percent of American adults play games and 75 percent of Americans have at least one game player in their household.14 Video games and game-like experiences have been prescribed by doctors15 to address complex health issues like addiction and substance abuse, and video games developers are using their craft to tackle depression, anxiety and other mental health issues head-on.16

Video games are even being integrated into classroom curriculums across a wide variety of subjects.17 Recently, competitive gaming and esports (games as spectator sports) have increased their presence in high schools as part of collegiate pathways through athletics and scholarships.

Yet, as ADL Belfer Fellow Gabriela Richard and colleagues suggest, "As the legitimacy of esports increases at a societal level, we must more meaningfully attend to the variety of ways differential access may affect educational and professional opportunities for historically marginalized groups.”18

ADL’s Belfer Fellow Dr. Karen Schrier has written extensively on the ways in which games of all stripes -- from big budget online first-person shooters to simple games using only shapes and colors -- can be used to promote ethical decision making, empathy, bias reduction and can even be used to solve real-world problems.19 Her recent paper for ADL, Designing Ourselves: Identity, Bias, Empathy and Game Design, explores the ways in which the practice of game design can be used to encourage game developers, and people more generally, to explore their own identity and take on new perspectives.20

At the same time, the toxic and exclusionary culture surrounding games goes back to the early days of digital games. Dr. Richard has written about how researchers have been studying the exclusionary nature of game design in terms of gender in various ways since at least the 1980s.21 Intersectional approaches to exploring the culture and practice of games, including analysis of how games operate in relation to race, sexual orientation, gender identity and ability have been more recently gaining ground in the study of games.22

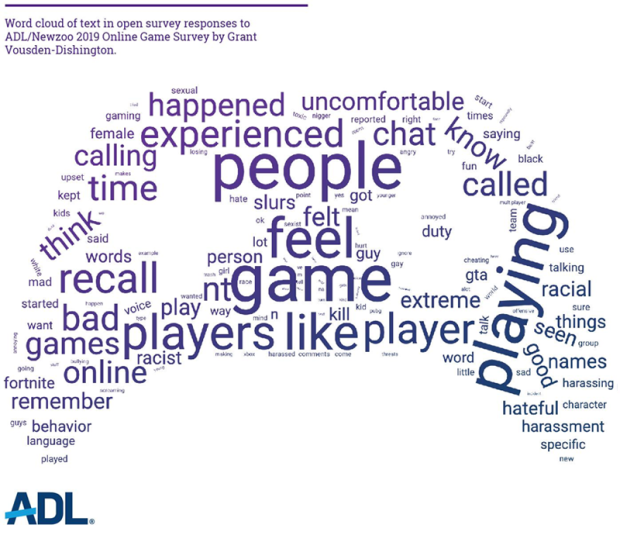

Games and game players have changed dramatically and dynamically from the earliest studies of gaming to present time. For example, in 2004 the average age of a US game player was 2923, while the average age of a US game player in 2018 was 34. In 2004, thirty-nine percent of game players identified as women,24 whereas 45 percent of the US game players identified as women in 2018.25 Even so, toxic culture and exclusionary practices continue in games. A longitudinal, mixed methods study of game players, initiated by Dr. Richard, explored how between 2009-13 a cross section of game players had experiences of harassment as a form of gatekeeping and silencing in social game spaces. For example, in the study, a 29 year old female Latina player described her experience playing games socially:

“They would send me pictures of things I didn’t want to see, or they would harass me, or if I were good, because I was great at Call of Duty 4, they’d say I was a guy playing under a girl’s name… I don’t talk on the mic, I just play… I just stopped talking cuz they’d be like, “oh that’s a girl, let’s harass her or ask for her number or something.” 26

Her experience is echoed by a wide variety of players included in the study. This broader trend of harassing and silencing people because of their identities was most publicly evident in 2014’s Gamergate event-— a coordinated harassment campaign that targeted women in the games industry. Gamergate also targeted individuals belonging to a wide cross section of marginalized groups who called for and were working toward games becoming more inclusive. Gamergate involved severe forms of harassment, like doxing and threats of physical violence, that often made online life extraordinarily difficult for those targeted and impossible for outspoken targets to work in the games industry and sometimes to even move freely in public.

This report provides a snapshot of online multiplayer games as social platforms in the US. The games represented in this survey are some of the most popular online multiplayer games being played in the US as of April 2019. This is important to note, as this survey does not focus on the large number of people and companies dedicated to creating and playing games beyond commercially focused mass market games.That said, it is our hope that through this report we can encourage game designers, game players, government and civil society to consider these popular online video game platforms with the same seriousness that surround conversations around the impact of mainstream social media platforms.

Methodology

ADL designed a nationally representative survey to examine Americans’ experience of hate, harassment and positive social experiences in online games in collaboration with Newzoo, a data analytics firm focusing on gaming and esports. We collected 1,045 responses from a base of adults 18-45 years old who play games across PC, console and mobile platforms, including 751 responses from people who play multiplayer online games. We oversampled individuals who identify as LGBTQ+, Jewish, Muslim, African American and Hispanic / Latinx. For the oversampled target groups, responses were collected until at least 60 Americans were represented from each of those groups. Surveys were conducted from April 19th to May 1, 2019. The margin of error based on our sample size is four percentage points in general, though this may be slightly higher when looking at smaller sample sizes.

In addition to being asked about positive social experiences in online games, respondents were asked whether and how often they experienced “disruptive behavior.” We defined “disruptive behavior” as the experience of being:

- The target of trolling/griefing (deliberate attempt to upset or provoke)

- Personally embarrassed by another online player

- Called offensive names

- Threatened with physical violence

- Harassed for a sustained period of time

- Stalked (online monitoring/information gathering used to threaten or harass)

- Sexually harassed

- Discriminated against by a stranger (based on age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.)

- Had personally identifying information made public (known as doxing).

In the following analysis, we refer to these forms of disruptive behavior as forms of harassment. We consider harassment hate-based when the activity or actions are clearly motivated by the identity of the target.

Results

Positive Social Experiences

The positive aspects of digital social spaces that exist inside online games include the opportunity they provide people to connect, build friendships and communities and allow for learning and knowledge sharing. In fact, according to our results, positive social experiences are incredibly common in online game environments.

Eighty-eight percent of online multiplayer gamers have experienced some form of positive social interaction while playing online multiplayer games, including making friends (51%) or helping other players (50%). Nearly a third of players (30%) felt like they belonged to a community in an online game, and a third (32%) discovered new interests as a result of playing an online game.

Twenty percent learned about themselves and 28 percent learned about interesting topics in online game environments. Eight percent found a mentor and 13 percent have found a partner through an online game. These findings indicate that online multiplayer games can facilitate deep social connection among players and meaningfully impact their lives.

We also looked at positive experiences by identity category to investigate whether these experiences are more common among certain groups. We found that over 80 percent of online multiplayer gamers across many gender identities, races/ethnicities, religions and sexual orientations have had positive social experiences while playing an online game.

At their best, online games can function as social platforms connecting people and building communities for a multitude of lived experiences. Notably, however, 43 percent of online multiplayer gamers who had a positive social experience in a game also quit or started avoiding at least one game as a result of harassment. In fact, 97 percent of players who quit or avoided a game also acknowledged having a positive experience in an online game at some point. Despite having positive experiences, the intensity of harassment for these players in some spaces was enough to motivate players to remove themselves from some game environments.

Positive Social Experiences by Game

Fifty-nine percent of individuals who played World of Warcraft (WOW) had positive social experiences in the game, making it the game with the highest percentage of players who have had positive experiences in it. Fifty-five percent of Minecraft players had a positive social experience in game, while 51 percent of players have ever had positive social experiences in NBA 2K.

Roughly half of players had positive social experiences in Overwatch, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Fortnite. These three games are notable because they are each first- or third-person shooters of various types and structures. Shooters have been a central aspect of public discussion about video games and their relationship with gun violence and morality . That said, these results point to a non-trivial amount of US adults having positive social experiences in an online shooter: making friends, learning about oneself or others and finding community.

Hate and Harassment

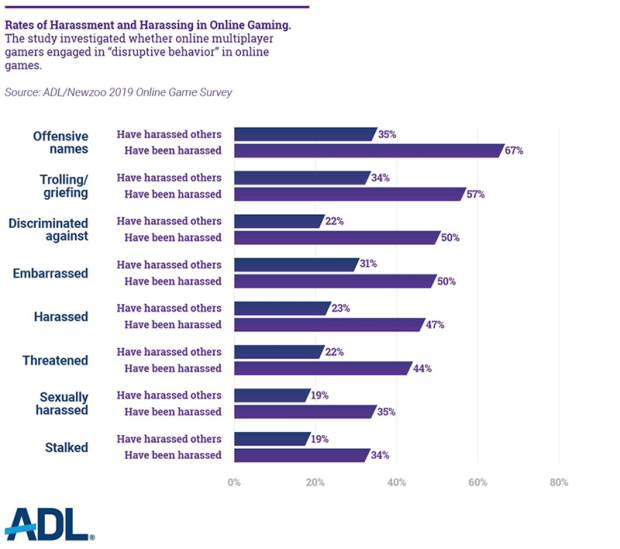

In addition to highlighting the less well-known positive characteristics of online games as social platforms, the survey nevertheless also found widespread harassment. Nearly three quarters (74%) of online multiplayer gamers have experienced some form of harassment in online multiplayer games. Sixty-seven percent have experienced being called offensive names in online multiplayer games, while 57 percent of online multiplayer gamers have been the target of trolling, meaning players were the target of deliberate and malicious attempts to provoke and antagonize them into some form of negative reaction.

Sixty-five percent of online multiplayer gamers have experienced more severe forms of harassment. Sixty-two percent reported being directly harassed for a sustained period of time, and 50 percent have been discriminated against by a stranger on the basis of their identity. Forty-four percent have been threatened with physical violence, and 44 percent have been stalked, meaning their online presence had been monitored in game and the information gathered was used to threaten or harass them.

Perhaps most alarmingly, 29 percent of online multiplayer gamers report having been doxed (“had a stranger publish private information about me”) in an online game, though the precise form this took or the extent of the experience was not further explored in this survey. Although the survey did not gather additional information about the results of these experiences, this type of exposure of information can result in sustained harassment outside of online games and can severely impact a person’s relationships, employment and mental health.

Identity or Hate-Based Harassment

Hate-based harassment is when players become targets of harassing behaviors on the basis of their identity, including but not limited to their gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, religion or membership in another protected class. Fifty-three percent of online multiplayer gamers who experienced harassment believed they had been targeted at some point based on their race/ethnicity, religion, ability, gender or sexual orientation.

Exploring identity-based harassment reveals that gender and sexual orientation are often the basis for abuse: 38 percent of women and 35 percent of LGBTQ+ game players reported harassment on the basis of their gender and sexual orientation, respectively. Approximately a quarter to a third of game players who were Hispanic/Latinx (24%), black or African American (31%), and Asian-American (23%) experienced harassment because of their race or ethnicity. Online multiplayer gamers are also targeted because of their religion: 19 percent of both Jews and Muslims report being harassed because of their religion.27

Harassment by Game

This study looked specifically at players’ experiences of harassment in several prominent online games in the US. These games were selected by ADL and Newzoo as being among the most popular in the US as of April 2019. They run the gamut from first-person shooters, strategy games, card games, sports simulators and role-playing games. Just as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are dominant among traditional mainstream social platforms, the popular games included here capture a large portion of the online gaming population. Several popular online game franchises that were not included in this survey include Call of Duty, Fallout, Halo, Destiny and FIFA. We did not include these games either because we wanted to cover a broad range of types of games and could not include every example of a particular genre (shooters, for example). Further, we wanted to focus on games most popular in the US.

In each of the 15 online games included in the survey, at least half of players reported that they had experienced some form of harassment. For example, in Minecraft, 51 percent of players experience some form of in-game harassment.

Seventy-nine percent of those who played DOTA 2 (Defense of the Ancients 2) reported experiencing in-game harassment, with 38 percent of DOTA 2 players being harassed frequently—making it the game with the highest proportion of players who experience harassment among the games we included.

Three shooters were reported as containing the next highest percentage of players who experienced in-game harassment:Three-quarters of players of Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO), Overwatch, and PlayerUnknown: Battlegrounds (PUBG) experienced some in-game harassment, with roughly a quarter of players reporting frequent harassment in each of these three games.

Both the games CS:GO and DOTA 2 were developed by Valve Corporation.This means that Valve Corporation games are in first and second place for highest proportion of game players who experience harassment in online multiplayer games included in this survey.

Three-quarters of League of Legends players also experienced in-game harassment, with 36% experiencing frequent harassment. Of the five games where players experienced the most harassment, League of Legends is the most popular in terms of number of players, with an estimated 118 million players globally and a thriving esports scene.28 This is also notable because League of Legends is the oldest of these games. It launched in 2009, and still maintains hundreds of millions of users ten years later. That said, our survey showed that 27 percent of League of Legends players end up quitting or avoiding the game due to harassment. In terms of positive social experiences, League of Legends ranked 12 out of 15 on our list of games, with just 37 percent of players reporting positive social experiences in game. This is particularly noteworthy , as League of Legends overhauled their in-game system to reward positive behavior in 2016, and has reported on its success in reducing harassment.29

Another extremely popular game, arguably one of the most popular games in the world at the moment, especially in Western countries, is Fortnite, which has registered 250 million players worldwide as of March 2019.30 According to our survey, 70 percent of Fortnite players have experienced some form of harassment in game, while 26 percent experience harassment frequently. Additionally, 36 percent of Fortnite players have quit or avoided the game as a result of harassment, making it the second most quit or avoided game among those included. While 47 percent of Fortnite players have had positive social experiences in the game, these harassment statistics in such a popular game should give its creators at Epic Games pause.

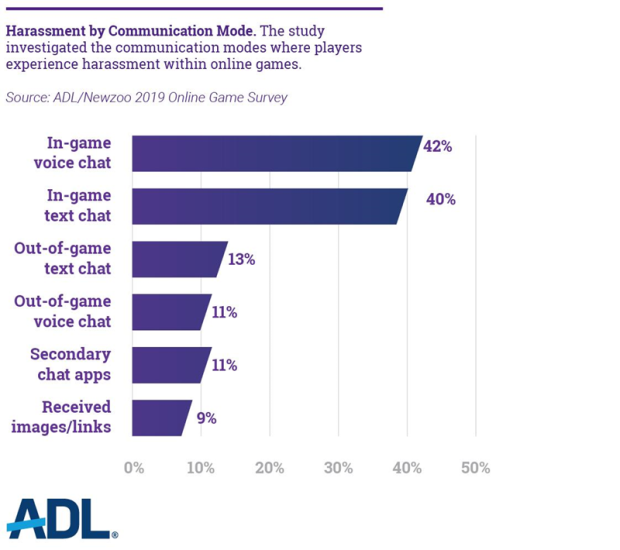

The study also investigated the communication modes where players most often experience harassment within online games. Many online multiplayer gamers experience at least some harassment as part of in-game voice chat (42%) and in-game text chat (40%). Less than a quarter of players experience harassment in other game-connected communication modes, such as secondary-chat apps (11%) and out-of-game text chat (13%).

Player Participation in Harassment

We included questions about whether online multiplayer gamers engaged in eight specific types of “disruptive behavior” in online games. We used the term “disruptive behavior” in the survey because harassment has such specific connotations that we were concerned using the term would result in biased answers. The behaviors, however, are all consistent with harassment and parallel the types of harassment we asked about earlier in the survey. Our results indicate that 46 percent of players engage in some form of online harassment in online multiplayer games.

More than 30 percent of online multiplayer gamers have called other players offensive names (35%), trolled or griefed other players (34%) or purposefully embarrassed them (31%). In terms of severe harassment, 38 percent of players had at some point engaged in at least one of the severe forms of harassment in online games.

For each type of severe behavior, around 20 percent of online multiplayer gamers have ever engaged in this behavior to some degree, and around 7 percent engage in these severe behaviors frequently. These players and players like them are likely to have been harassment targets as well: 96 percent of those who identified as harassers have experienced harassment themselves.

Extremism, Conspiracy Theories and Disinformation

ADL has been analyzing the ways in which new technologies and digital spaces can be weaponized by extremists and bad actors to amplify their hateful agenda since the mid-1980s. Much has been made of the connection between extremists and the game community, with some claiming that extremists of various belief systems have been infiltrating online games in order to radicalize players to adopt their hateful ideology.31 In order to assess these anecdotes and claims, the survey included questions about whether players were exposed to specific controversial topics in online games. The results confirm that these topics are being discussed in online game environment, though we cannot say to what extent people were exposed nor in what context (e.g., if it was related to radicalization or recruitment).

Almost a quarter of online multiplayer gamers (23%) have been invited to discuss or have heard others discussing the “superiority of whites and inferiority of non-whites” and/or “white identity/a home for the white race.” The “superiority of whites” is a core tenet of white supremacist ideology, that posits that the “white race” is in every way superior to other identities such as Jews and people of color. White supremacist ideology is at its core anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim, racist and sexist. While this result does not necessarily imply that players were being recruited to join a white supremacist organization in any online game, the prevalence of expressions of white supremacy in online games suggests that this hateful ideology may be normalized in some game subcultures.

Also, 13 percent of online mutliplayer game players were exposed to disinformation about the 9/11 attack on the United States, 9 percent of online multiplayer gamers were exposed to denials of the scope and impact of the Holocaust, 8 percent of players were exposed to positive views of the activities of Islamic state/ISIS, 8 percent were exposed to positive views of Gamergate and 8 percent of players were exposed to disinformation about vaccinations. Though the exact context and content of these exposures is not known, these numbers are alarming, and point to the need for much further investigation on extreme viewpoints and disinformation in games.

The Impact of Hate and Harassment on Players

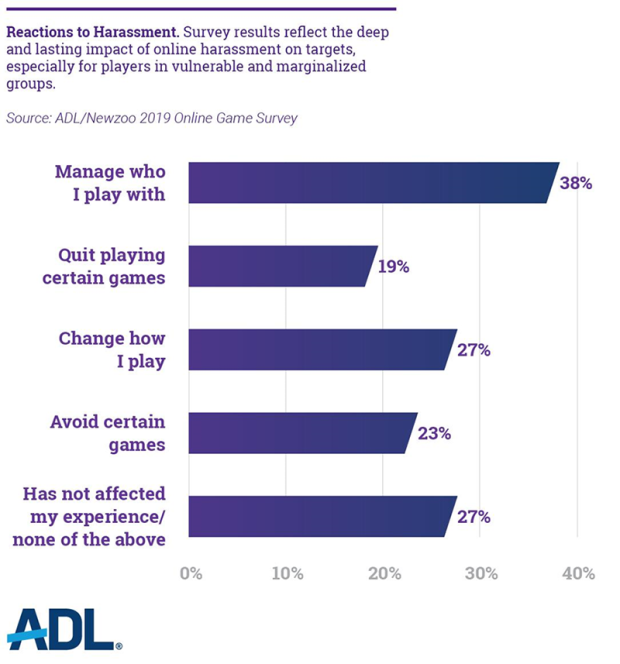

This survey sheds light on the impact of harassment in online games on players: how they alter their play in online games, and the impact of harassment on their daily lives outside of games. In both cases, the results reflect the deep and lasting impact of online harassment on targets, especially for players in vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Thirty-eight percent of online multiplayer gamers have become more careful about who they play games online with out of concern for online harassment. Twenty-seven percent have changed the way they play out of concern for harassment. Examples we gave people in the survey regarding how they changed their mode of play included, “not using in-game voice chat” and “changing their username”

In fact, 23 percent of online multiplayer gamers who have been harassed avoid certain games due to a game’s reputation for having a hostile environment and 19 percent have stopped playing certain games altogether as a result of in-game harassment. Perhaps most notable is that only 27 percent of online multiplayer gamers reported that harassment had not impacted their game experience at all, meaning that fully 73 percent of players had their online multiplayer game experience shaped by harassment in some way.

The games that most players either become more careful playing or stop playing altogether as a result of harassment are DOTA 2 (37%), followed by Fortnite (36%), Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (36%), NBA 2K (33%), Madden NFL (31%), Overwatch (29%), Apex Legends (28%), World of Warcraft (27%) and League of Legends (27%).

Additionally, of all game players in the survey, 27 percent stated that they play games, but never play games online. Thirty-six percent of these offline game players stated they would be more likely to play online if steps were taken to address hate and harassment in online games.

The impact of harassment in online games goes beyond the game environments, and can have a significant impact on players’ lives. The population of game players in the US was around 178 million in 2018.32 Extrapolating from existing data and our results, we can estimate that 73 million American adults play online games.33

Based on that, it can be surmised that somewhere between 6 and 16 million American adults (between 8% and 23%) are adjusting how they socialize, considering self harm or taking precautions to ensure their physical safety because of the negative experiences in online games. More than that, the negative experiences in games impact the personal relationships and school performance of 5 to 6 million Americans (between 7% and 8%). Our results indicate that five percent of players targeted call the police. This implies that roughly 3 million Americans have contacted the police because of harassment in online multiplayer games. Despite the widespread nature of this behavior, only 12 percent of players reported harassment to the game company, implying there is much more for the industry to do to inspire the trust of players to address this problem.

Player Attitudes and Suggestions for Industry

Consistent with their experiences, roughly half of players see online multiplayer games as both positive social spaces (49%) and having widespread toxicity (55%). A majority of players (62%) feel that companies should do more to make online games safer and more inclusive for players.

In terms of support for specific courses of action to help alleviate the problem of harassment in online games, over half of players believed that targets of harassment in online games should have more legal recourse to seek justice against perpetrators for the real harms caused by these incidents (58%).

Another specific solution that had majority support from game players was the development of content moderation tools for in-game voice-chat. Over half of players(55%) agree that games should have technology that allows for content moderation in in-game voice chat, in the same way that there are currently technologies that allow for content moderation for in-game text chat.

Endnotes:

2. Doxing or doxxing (from "dropping documents") is the internet-based practice of researching and broadcasting private or identifying information (especially personally identifying information) about an individual, group or organization. In the gaming context, doxing commonly manifests as personal information and is posted in chat and streaming comments.

3. These numbers should be interpreted with caution, as the sample size for Jewish and Muslim respondents was small.

4. Richard, G.T. (2016). At the Intersections of Play: Intersecting and Diverging Experiences Across Gender, Identity, Race, and Sexuality in Game Culture. In Y.B. Kafai, G.T. Richard & B. Tynes (Eds.), Diversifying Barbie and Mortal Kombat: Intersectional perspectives on gender, diversity and inclusivity in gaming. ETC/Carnegie Melon University Press.

6. http://www.british-legends.com/CMS/index.php/about-mud1-bl/history

8. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habitat_(video_game)

9. https://massivelyop.com/2015/05/02/the-game-archaeologist-aols-neverwinter-nights/

10. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00300.x#b61

12. https://resources.Newzoo.com/hubfs/Reports/Newzoo_2018_Global_Games_Market_Report_Light.pdf

14. https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ESA_Essential_facts_2019_final.pdf

15. https://www.wired.com/story/prescription-video-games-and-vr-rehab/

18. Steinkuehler, Constance. “Schools Use Esports as a Learning Platform: California High Schools Encourage Students to Use Online Video Games to Learn Science, Technology, Engineering and Math – and a Variety of Soft Skills As Well.” US News and World Report, 12 June 2018. https://www.usnews.com/news/stem-solutions/articles/2018-06-12/commentary-game-to-grow-esports-as-a-learning-platform.

Richard, G.T., McKinley, Z. A. & Ashley, R.W. (in press). Collegiate Esports as Learning Ecologies: Investigating Collaboration, Reflection, and Cognition During Competitions. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association (ToDIGRA Journal).

19. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261993; https://www.amazon.com/Knowledge-Games-Problems-Education-Technology/dp/1421419203 https://www.adl.org/blog/how-we-can-use-games-to-understand-others-better;

20. https://www.adl.org/designing-ourselves

23. https://www.scribd.com/document/125494009/ESA-Essential-Facts-2004

24. https://www.scribd.com/document/125494009/ESA-Essential-Facts-2004

25. https://www.theesa.com/esa-research/2019-essential-facts-about-the-computer-and-video-game-industry/

26. Kafai, Yasmin & Richard, Gabriela & Tynes, Brendesha. (2016). Diversifying Barbie and Mortal Kombat: Intersectional Perspectives and Inclusive Designs in Gaming. Chapter 5: At the Intersections of Play by Gabriela T. Richard

27. These numbers should be interpreted with caution as a smaller number of respondents identified themselves explicitly as Jewish or Muslim.

28. https://rankedkings.com/blog/how-many-people-play-league-of-legends

30. https://www.statista.com/statistics/746230/fortnite-players/

31. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/27/opinion/gaming-new-zealand-shooter.html

32. https://Newzoo.com/insights/infographics/us-games-market-2018/

33. According to the Entertainment Software Association, 58 percent of those game players are between 18 and 49, which roughly translates to around 103 million people out of the original 178 million. According to our results, 71 percent of overall respondents play online games, which would translate to roughly 73 million Americans out of 103 as online multiplayer gamers between 18 and 49.

Recommendations

For the Game Industry

- Develop a rating system that gives meaningful information to consumers about the nature of the game’s online community: The current major rating system for games is the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) system.1 Originally designed in 1994, the ESRB rating system was designed for a time before the majority of gameplay took place online across multiple game platforms. Though the rating system has been updated over time, a game’s rating does not claim to rate games according to the nature of online interaction that might occur in them.

As a result, among the six games that were identified in our results as fostering widespread harassment, only two have “mature” ratings from the ESRB. A “mature” rating means the game’s intended audience are players 17 years or older. Three of the games are rated “Teen,” meaning that they are intended for players ages 13 years or older. One of them, DOTA 2, has no ESRB rating at all- providing players with no guidance as to whom the content of the game is appropriate for, let alone the online interactions accompanying it.

We recommend that the ESRB and the game industry work with outside experts on the nature of online social platforms to create a ratings system that provides meaningful information to consumers about the nature of communities and interactions in online games. The results of a survey such as this one could feed into a rating system, alongside evaluations of a game platform’s policies on hate and harassment, and their in-game mechanisms for allowing users to report. - Create tools for content moderation for in-game voice chat: Voice chat in online games is a major locus of harassment. Tools and techniques to detect hate and harassment for in-game voice chat lag far behind tools for evaluating and moderating text communication. A majority of game players support more content moderation for in-game voice chat.

The gaming industry, academia and civil society should invest in developing in-game voice chat content moderation. ADL’s Center for Technology and Society is currently in conversation with major companies in the tech industry to find ways to help push crucial research towards this technology in order to help make online games safer and more inclusive for all people.

- Strengthen policy and enforcement of terms of service: Many of the companies that make the games included in this survey have Codes of Conduct or Terms of Use that prohibit hate or harassment, but rarely do they go far enough in describing which communities they are meant to protect and what explicit behaviors are forbidden. We recommend companies specify the protected categories (including gender, gender identity, race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, ability) in their Terms of Use, and explicitly prohibit doxing. In developing these Terms of Use, we recommend that game companies consult with individuals and organizations who represent groups that experience high rates of harassment.

- Improve workplace inclusivity efforts: Game studios should embody in their own corporate culture the kinds of behaviors and communities they want to see on their game platforms, because this will make their products more inclusive. To help achieve this, studios should work towards creating an inclusive and supportive work and development environment and culture. This can include inclusive HR policies, a long-term commitment to regular anti-bias trainings for all employees and implementing supportive workplace practices that explicitly stand in opposition to “crunch culture.”2

- Establish industry-wide effort to address white supremacy: Given the high rate of discussion of white supremacist ideology in online game spaces, we recommend that the game industry support research into the use and abuse of online games by white supremacists. We recommend that the game industry work with experts on white supremacy and white supremacist ideology to find ways to counter their abuse of online games. Such research could include reviews of usernames for common extremist terms and sharing of information between companies on radicalization efforts.

- Increase transparency on harassment and hate on platforms While many social media companies currently provide limited transparency reports on these issues, no game company does. We recommend that game companies produce transparency reports that describe the prevalence of hate, harassment and positive social experiences in online games in order to inform the public and stakeholders in civil society of an accurate picture of the nature of various social interactions in online games,.

For Civil Society

1. Increase focus on how games impact vulnerable populations: Civil society organizations in the US have started to scrutinize the effects of traditional social media on users and society. It is equally important to take a serious look at the impact of games on players and society. Some organizations are already starting to do this work.

- ADL’s Center for Technology and Society is focused on fighting hate, bias and harassment in games and the game community. In that context, we have organized anti-bias game jams across the US, worked with leading researchers to explore the intersection of game design, empathy and bias, convened game industry leaders to discuss solutions to these important problems, and started advocacy efforts with game companies in the same manner that we have engaged social media companies.

- GLAAD added a category to its media awards that highlighted LGBTQ+ representation in video games.3 The fact that a prominent and historic advocacy group is using its platform to highlight the role games play in the industry demonstrates the growing importance of this issue for the community GLAAD represents.

- Gaming-specific nonprofits are also engaging with these issues. For example, AnyKey focuses on creating inclusive spaces in competitive games and esports;4 AbleGamers works for inclusion and improved quality of life for people with disabilities through games;5 and Black Girl Gamers focuses on promoting diversity within the gaming industry.6 We believe partnerships between broad and gaming-specific groups could be a promising approach to achieving change.

2. Support game scholars and practitioners who have expertise on these issues to increase research. There are a wealth of incredible game scholars and practitioners in academia who have been working for at least the last 30 years, studying both how games can be used for social good and the real harms that games and game culture can do. We encourage civil society organizations to engage seriously with these researchers, and help to expand knowledge about both the positive and harmful impacts of games. ADL’s work in this space has benefited greatly from our partnership and collaboration with game scholar Dr. Karen Schrier as part of our Belfer Fellowship program. Her work focuses on games and learning, empathy and ethics, as well as using game design as a way to support anti-bias education, compassion and perspective-taking. In the coming year, we will collaborate further with new Belfer Fellow Dr. Gabriela Richard and her work on esports and livestreaming as an intervention method for game players. Just as ADL has created such partnerships, civil society organizations have the opportunity to investigate and engage with the research, practice and experts focused on specific communities.

For Government

-

1. Strengthen laws against perpetrators of online hate: Hate and harassment translate from on the ground to online spaces, including in social media and games, but our laws have not kept up. Many forms of severe online misconduct are not consistently covered by cybercrime, harassment, stalking and hate crime law. Legislators have an opportunity, consistent with the First Amendment, to create laws that hold perpetrators of severe online hate and harassment more accountable for their offenses, including at the state level:

- Ensuring hate crime laws cover crimes that take place online. Apart from Illinois, which mentions “cyberstalking,” no state hate crime statute expressly includes online conduct within its scope. These laws can and should be updated to explicitly cover applicable online crimes.

- States should close the gaps that often prevent stalking and harassment laws from capturing online misconduct. Improved laws can create better protections for victims and targets without creating constitutional complications.

Congress has an opportunity to lead the fight against hate in online games as well, by increasing protections for targets, by updating federal stalking and harassment statutes’ intent requirement to account for online behavior.

3. Improve training for law enforcement: Law enforcement is a key responder to online hate, especially in cases when users feel they are in imminent physical danger. Increasing resources and training for these departments is critical to ensure they can effectively investigate and prosecute cyber cases.

Endnotes:

Appendix: Disruptive Behavior Descriptions

In this survey, we asked about players’ experience of the following “disruptive behaviors” which we refer to as harassment in the report: We included six of these behaviors as examples of severe harassment. Those behaviors are listed and briefly described below.

Harassment

- Trolling/griefing: a deliberate attempt to upset or provoke

- Personally embarrassing another player

- Calling a player offensive names

Severe Harassment

- Threatening a player with physical violence

- Harassing a player for a sustained period of time

- Stalking a player (online monitoring / information gathering used to threaten or harass)

- Sexually harassing a player

- Discriminating against a player by a stranger on the basis of age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.

- Doxing (from "dropping documents"): the internet-based practice of researching and broadcasting private or identifying information (especially personally identifying information) about an individual, group or organization. In the gaming context, doxing commonly manifests as personal information and is posted in chat and streaming comments

Appendix: Survey Methodology

For a detailed description of the methodology used to conduct this survey, please review this resource.