Related Content

Executive Summary

Ninety-seven million Americans play online multiplayer games. While virtually all players surveyed in ADL’s third annual report on experiences1 in online games appreciated the social connectivity of gaming, an alarmingly large majority continue to encounter a firehose of hate and harassment. ADL’s survey explores the social interactions, experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of online multiplayer gamers nationwide. This year’s survey again asked about the experiences of a nationally representative sample of the nearly 100 million adult online multiplayer gamers in the United States. For the first time, it also included the experience of young gamers, ages 13-172.

For the third consecutive year, ADL’s survey found that harassment experienced by adult gamers increased and remains at alarmingly high levels, while the new research on the experience of teens also raises significant concerns.

In the past six months:

- Five out of six adults (83%) ages 18-45 experienced harassment in online multiplayer games—representing over 80 million adult gamers.

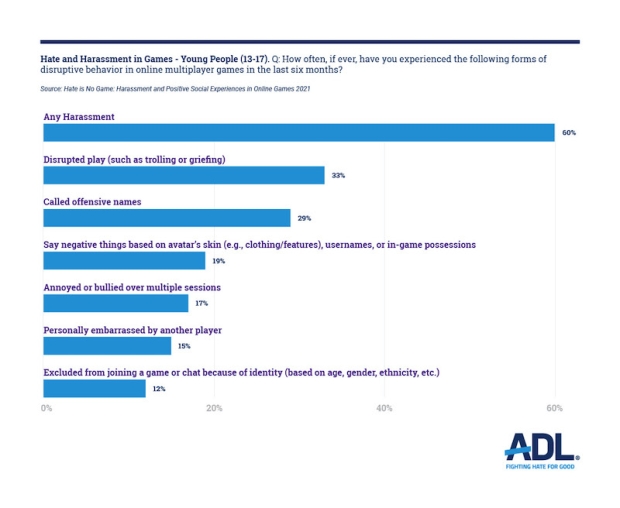

- Three out of five young people (60%) ages 13-17 experienced harassment in online multiplayer games—representing nearly 14 million young gamers.

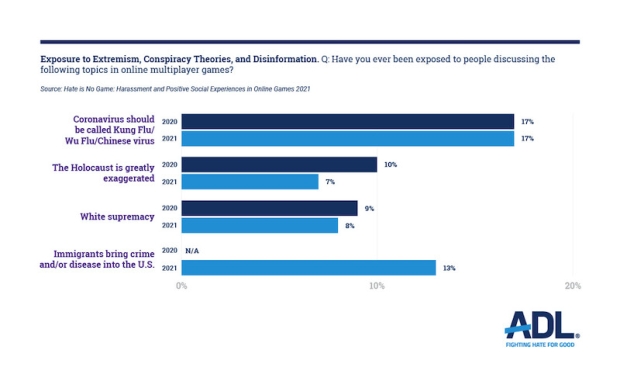

- 8% of adults ages 18-45 and 10% of young people ages 13-17 reported being exposed to discussions in online multiplayer games around white supremacist ideology, the belief that “white people are superior to people of other races and that white people should be in charge.”

- 7% of adult online multiplayer gamers were exposed to Holocaust denial while playing.

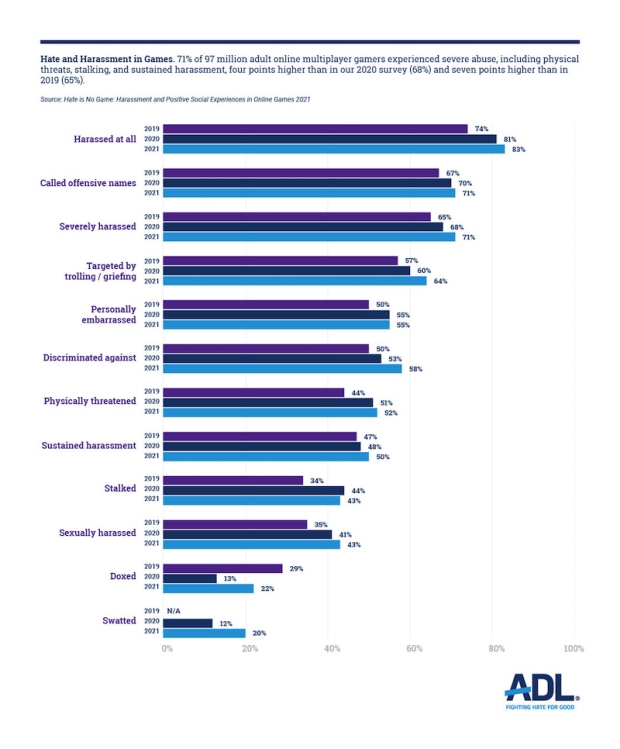

- 71% of adult online multiplayer gamers experienced severe abuse, including physical threats, stalking, and sustained harassment3, representing no significant change from our 2020 survey (68%) and six points higher than in 2019 (65%).

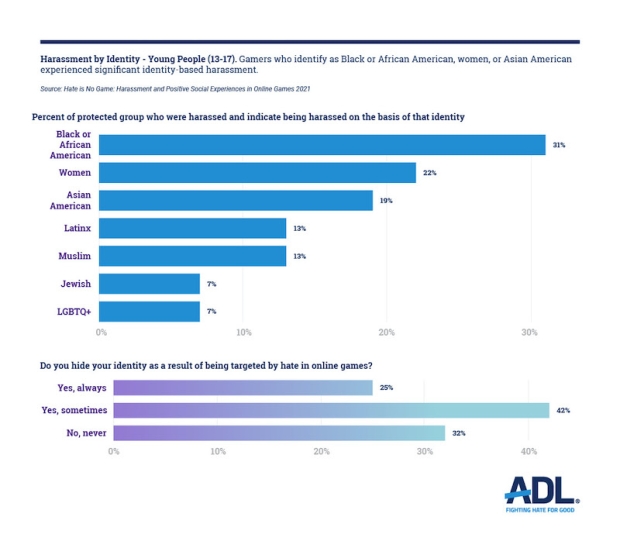

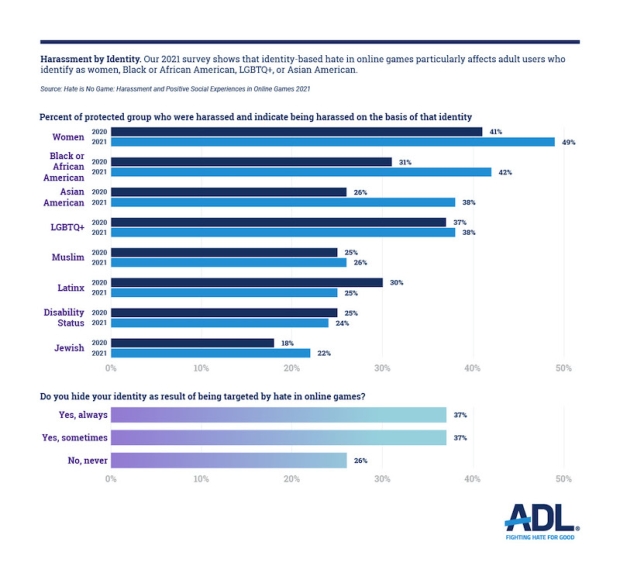

- The largest increases in identity-based harassment occurred among adult respondents who identified as women (49% in 2021, compared to 41% in 2020), Black or African American (42% in 2021, compared to 31% in 2020), and Asian American (38% in 2021, compared to 26% in 2020). It is worth noting that although there was no statistically significant change in identity-based harassment of adult LGBTQ+ players (38% in 2021 versus 37% in 2020), the number is still of concern.

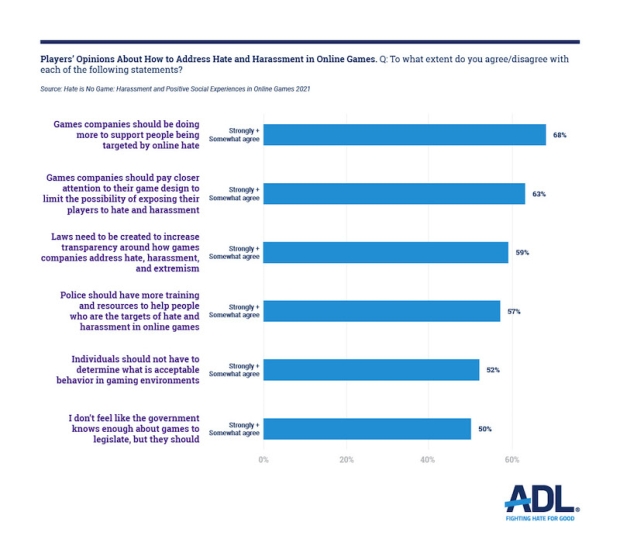

- 59% of adult gamers believe that laws need to be created to increase transparency around how game companies address hate, harassment, and extremism.

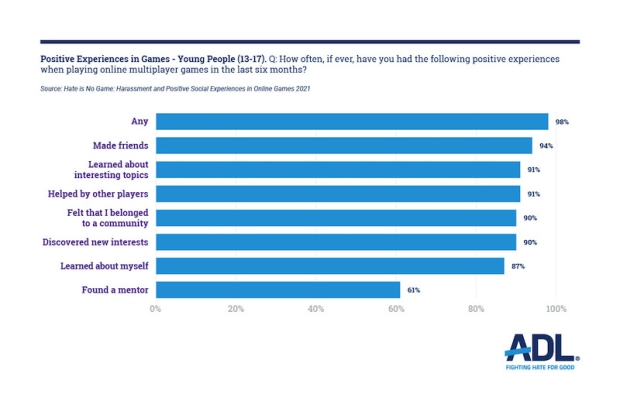

- 99% of online multiplayer gamers experienced some form of the positive social behaviors asked about in our survey.

Recommendations

There is a lot we can do to stem the tide of hate and harassment in online games:

- What the games industry should do: Harassment in online multiplayer games has increased for the past three years, so the games industry must act urgently. In 2020, ADL and the Fair Play Alliance released the Disruption and Harms in Online Gaming Framework to help the industry better define and address hate and harassment in online games. Games companies should adopt the framework, assess the efficacy of their current efforts to combat hate and harassment among users, increase their investments in staff and products, and make a practice of regular third-party audits to measure impact.

For young players, games companies should implement product safety controls as the default and should prompt a user to review all safety controls before playing. - What civil society should do: Many civil society organizations have expanded their work to document the impact of social media, particularly on vulnerable communities. Civil rights and education groups, among others, should now broaden their scope to address the impact of online multiplayer games. Civil society should support scholars and practitioners whose work helps fight hate, bias, and harassment in games. Civil society groups should also partner with newer nonprofits from the gaming space such as Take This, an organization that advocates for better mental health in game design; AnyKey, an organization that offers programs that foster diversity, inclusion, and equity in esports, to deal with these critical issues, GaymerX, which advocates for more and better LGBTQ+ representation in game content and in staff at major studios; Feminist Frequency works to end abuse in the games industry for developers and players; and Able Gamers advocates for greater accessibility in games for disabled players. Civil society should also insist that government conduct and support research and engage in education and oversight similar to the ways they have begun to employ with social media platforms.

- What government should do: Federal and state legislators and executive branch agencies should strengthen and enforce laws that protect targets of online hate and harassment, whether on traditional social media or in online multiplayer games. Currently, lawmakers are considering ways to increase transparency and accountability from social media companies; they should also compel the games industry to release transparency reports that provide meaningful online hate and harassment data. Government should support research and policy proposals on fighting extremism, hate, and harassment in online gaming. ADL’s REPAIR Plan expands on the priorities government must focus on to fight online hate.

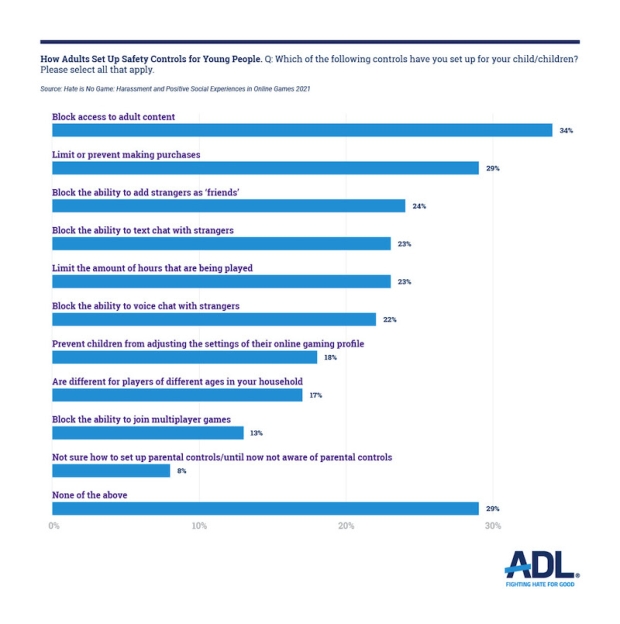

- What caregivers and educators should do: Less than 40% of parents or guardians of young people in the survey reported implementing safety controls in online multiplayer games that were part of this survey. Adults, including parents, educators, counselors, and others, should actively review safety features with children to ensure appropriate controls are turned on, such as blocking young people from having conversations with strangers via voice chat. Additionally, less than half of teenage gamers ADL surveyed talk to the adults in their lives about their experiences in online multiplayer games. Adults need to engage in meaningful conversations with young people about their gaming experiences.

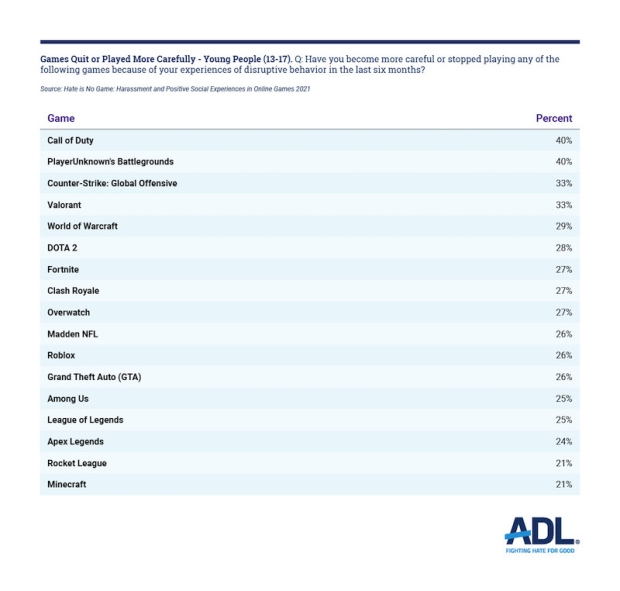

- What you should do: Consumer demand may be the best lever to move games companies to better address hate and harassment. Avoid purchasing games where high percentages of players report they quit or had to play more carefully.

ADL’s survey focuses on online multiplayer games, which form a subset of the overarching video game market. More than two out of three Americans—over 226 million people across all ages—play video games, including both online and offline games.4 Globally, video games are a financial and cultural juggernaut, larger than the movie and music industries combined. The video games industry is a $175 billion market, with the North American video game market generating over $42 billion in 20215. It is past time for the problem of hate and harassment in gaming spaces to be treated seriously.

In focusing on online multiplayer games, this report offers concrete guidance for the industry to take meaningful steps in making those games safer for all users, regardless of age or identity.

An Overdue Reckoning for the Games Industry

Toxic games may be influenced by toxic company cultures. In July 2021, the State of California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing filed a lawsuit against the major video games company Activision Blizzard stating that it created a culture of “constant sexual harassment.” The Department cited the tragic case of a woman employed by Activision Blizzard who was the target of intense sexual harassment and took her life on a company trip. Activision Blizzard experienced a severe and swift fallout soon after the litigation was filed; a walkout by employees, in-game protests, its president stepping down, major advertisers backing out of sponsorship deals, and a letter from a shareholder demanding change all happened within weeks.

After years of stories of gender-based discrimination, it appears the games industry is facing a reckoning. Although allegations of sexual harassment and toxicity against major games companies have been reported before, most recently at Ubisoft in 2020 and Riot Games in 2018, the Activision Blizzard suit may prove to be a watershed moment for the industry heralding systemic change. In an interview with The Guardian, Amanda Cote, assistant professor of media studies/game studies at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication and the author of Gaming Sexism, said:

What seems to be different now is the fact that people are recognizing these issues as being systemic and repeated rather than episodic. People seem to be calling for change across the industry, rather than just at one company at a time.

A game company's work environment can affect how online games are created and which player behaviors are tacitly condoned by the game design. Last year, ADL and the Fair Play Alliance released the “Assessing the Behavior Landscape” guide as part of the Disruption and Harms in Online Games Framework. The guide helps games companies decide what kinds of behavior they want to see in the online multiplayer games they create or currently manage. The first step is for a games company to define its vision: What values should companies express in their games? The guide urges games companies to take stock of their values, think of how those values can and should be encouraged in their games, and list what behaviors in a game run contrary to those values. Companies must understand that if they are not explicit about their values and working towards a well-articulated vision of their games, their unspoken and implicit values will directly influence what behaviors are tolerated in their games.

The high levels of harassment reported by the participants in ADL’s surveys over the past three years mirror the ongoing problems of workplace harassment in the games industry. We advise readers to think about our report within this context. We are hopeful that public and internal pressure will force games companies to confront the spread of hate and harassment in their workplaces and in their games.

Survey Methodology

ADL, in collaboration with Newzoo, a data analytics firm focused on games and esports, designed a nationally representative survey to examine Americans’ experiences of positive social interactions and disruptive behavior in online multiplayer games. We collected responses from 2,206 Americans (542 children, ages 13-17, and 1,664 adults, ages 18-45) who play games across PC, console, and mobile platforms, including 1,827 responses from people who play online multiplayer games. For young people ages 13-17, we also collected responses from their parents or guardians as part of the screening process.

We oversampled individuals who identify as LGBTQ+, Jewish, Muslim, Black or African American, and Hispanic/Latinx. Additionally, we have a representative sample of Asian Americans. We collected responses for the oversampled target groups until at least 180 Americans were represented in each group. Surveys were conducted from June 7 to June 25, 2021. The margin of error based on our sample size is generally two to three percentage points, though this may be slightly higher when looking at smaller sample sizes.

In addition to questions about positive social experiences in online games, we asked adult respondents ages 18-45 whether and how often they experienced “disruptive behavior” including:

- Trolling/griefing (deliberate attempts to upset or provoke someone)

- Another online player embarrassing them

- Offensive name-calling

- Threats of physical violence

- Sustained harassment or harassment that occurs over multiple game sessions or a longer period of time

- Stalking (online monitoring/information gathering used to threaten or harass)

- Sexual harassment

- Discrimination by a stranger (due to age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.)

- Doxing, which is having personally identifying information made public

- Swatting, when a stranger makes a false report to emergency services to target someone

We also asked young people ages 13-17 about their experiences of disruptive behavior, but altered the categories slightly. We changed the wording in some cases to focus on disruptive behaviors young people may be more familiar with and limited questions around other behaviors to avoid subjecting young participants to additional harm. For example, we did not ask young people about their experiences with threats of physical violence or sexual harassment. We asked the teenagers:

- Had players say or do things that have disrupted my play (such as trolling or griefing)

- Been personally embarrassed by another player

- Been called offensive names

- Had the same people annoy or bully me over multiple sessions

- Had players say negative things to me based on my avatar/character’s skin (e.g. clothing/features), my username, or my in-game possessions

- Been excluded from joining a game or chat because of my identity (based on age, gender, ethnicity, etc.)

- Prefer not to say

- None of the above

In the following analysis, we refer to the forms of disruptive behavior experienced by adults or young people, as described above, as harassment.

Results

Young People (13-17)

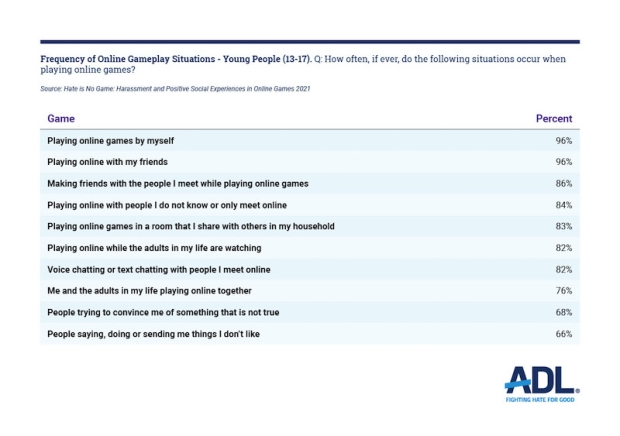

Social Experiences in Online Gaming

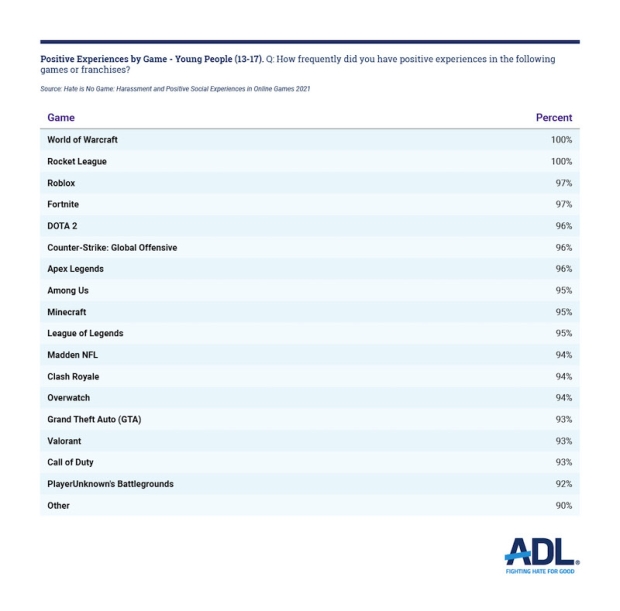

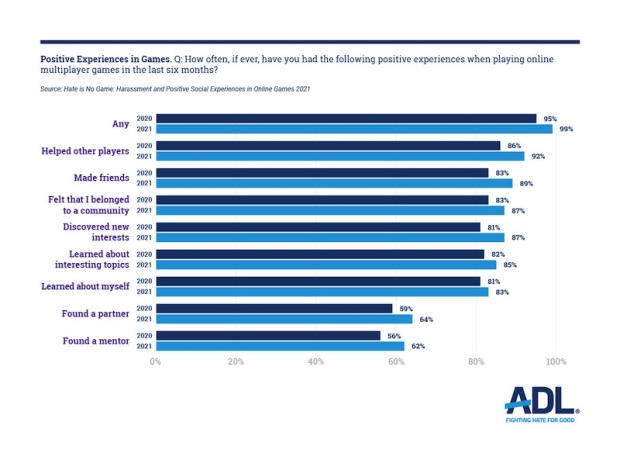

Twenty-three million out of the 26 million gamers ages 13-17 in the U.S. play online multiplayer games. The vast majority of young gamers—more than nine out of ten—reported some form of positive social experience in online multiplayer games. World of Warcraft and Rocket League had the most young gamers reporting positive experiences.

Harassment affects the majority of young people. Three in five young people experienced harassment in online multiplayer games—nearly 14 million young gamers.

Hate and Harassment in Online Games

Identity-based harassment was a problem for young gamers who identified as Black or African American, women, and Asian American.

As a result of being targeted by hate in online games, 25% of young players said they always hide their identity when playing online while 42% said they sometimes hide their identity.

Exposure to Extremist White Supremacy

We asked young gamers about their exposure to extremist white supremacist ideologies in various contexts, including online multiplayer games. Specifically, we asked if they were exposed to people who “believe that white people are superior to people of other races and that white people should be in charge” after explaining to respondents the hateful, racist, and antisemitic nature of this ideology.

We found that one in ten young gamers were exposed to white supremacist ideologies in the context of online multiplayer games. The other results presented here pertain to young people 13-17 who play online games but encountered white supremacist ideologies in other contexts.

The Impact of Hate and Harassment

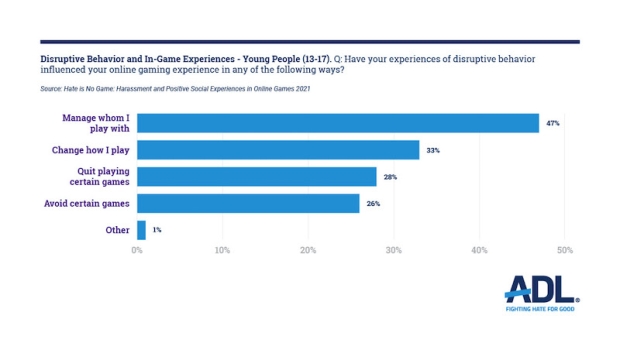

The harassment that young people experience in online multiplayer games affects their online and offline lives. Over a quarter of young gamers who experienced harassment in online multiplayer games quit specific games. A third of young gamers changed how they play, including not speaking in voice chat and altering their usernames. Voice chat is notorious for being a significant locus of in-game abuse. A username that refers to a player’s gender, race, or other identity characteristic also can serve as a target for harassment.

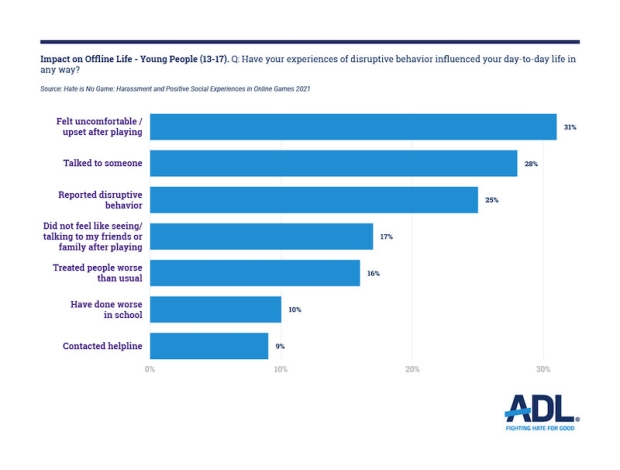

In-game harassment has offline consequences for young people. Sixteen percent of young gamers in the U.S. reported that they treated people worse than usual and 10 percent reported their school performance declined.

The Role of Adults in Young People’s Online Gaming Lives

We asked both young gamers and the adults (parents or guardians) in their lives about the kinds of conversations they have with each other regarding online multiplayer games. The most frequent topic teenage gamers reported discussing with adults was which games they play (42% of all teen gamers surveyed). Only 32% of the parents or guardians of the teenagers surveyed reported discussing how often the young people in their lives play with new people. The same percentage of these parents (32%) discussed whether the young people in their lives know how to report abuse.

We also asked about the safety controls parents or guardians put in place for young people in online games. Less than half of parents or guardians surveyed reported having implemented the safety controls in online multiplayer games that were analyzed in this survey.

Adults (18-45)

Social Experiences in Online Gaming

Online games at their best can function as social platforms connecting people and building communities for a multitude of lived experiences. Out of the 123 million adult gamers 18-45 in the U.S.,6 97 million play online multiplayer games. Nearly all of these players—more than 9 in 10 adult gamers—reported having some positive social experiences when they played online multiplayer games.

Hate and Harassment in Online Games

Although positive social experiences in online multiplayer games are widespread, so are hate and harassment. For the third consecutive year, harassment in online games has not decreased. Five out of six adult gamers experience harassment in online multiplayer games—more than 80 million American adults.7

Severe harassment in online multiplayer games is commonplace. 71% of adult online multiplayer gamers reported experiences of severe abuse, including physical threats, stalking, and sustained harassment—almost 70 million American adults.8

For the 2021 study, we repeated last year’s methodology to collect more granular and accurate data regarding swatting and doxing. Like last year, we used a broader definition for doxing in our survey than the legal definition of unlawful doxing, because at present there is no consistent legal standard. In our questions, we provided the following broad definitions for doxing and swatting:

- Doxing is making personally-identifying information public

- Swatting is when a stranger makes a false report to emergency services to target someone

We then asked respondents who experienced either to describe what happened. In our total figures for swatting and doxing, we included the responses of some players who reported something similar to either behavior or who preferred not to elaborate. We removed descriptions unrelated to swatting or doxing from our final numbers. Based on this methodology, 22% of respondents were doxed and 20% were swatted.

I was playing Call of Duty and the person I was playing against got mad and somehow found my personal information. This includes my email, my full name, my phone number and even my address.

—21-year-old male, Black/African American, and atheist gamer

I was just playing Valorant with voice chat and after winning I was harassed and told my address would be leaked by the opposite team. He then proceeded to read out my address.

—31-year-old female, Hispanic/Latinx, and heterosexual gamer

He called the police on me and said I was hacking and that it was terrible and they came to my doorstep to ask questions. i wasn't hacking and they realized it was a game

—20-year-old female, Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and lesbian gamer

Cops came to my place but soon realized it was a prank.

—24-year-old male, Hispanic/Latinx, Catholic, and bisexual gamer

We believe these numbers provided by our updated methodology present a more accurate picture of the experience of American adults who are doxed and swatted in online multiplayer games.

Identity or Hate-Based Harassment

Hate-based harassment is defined as targeting players for disruptive behaviors based at least in part on their actual or perceived identity, including, but not limited to, age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, religion, or membership in another protected class. For the third year in a row, gender was the most frequently cited reason for abuse.

The increase in hate against Black or African American and Asian American players is also notable in that it coincided with the games industry’s increased public activity around issues of anti-Black and anti-Asian hate in America. Last year, in our 2020 survey, ADL tracked statements and commitments by the games industry expressing support for the Black community and the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. This year, ADL tracked games industry statements and commitments expressing support for the Asian American community, following the spa shootings in Atlanta, Georgia, in March 2021. However, our survey shows that even as the industry spoke out against hate targeting Black and Asian communities, these same groups experienced double-digit increases in identity-based harassment in online games.

Extremism, Conspiracy Theories, and Disinformation

The relationship between extremist movements and the video games community is an area of growing importance and was the subject of a public forum in March 2021 organized by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, at which ADL staff spoke. Investigations, such as a Wired article on Roblox that examined how young users create in-game spaces rooted in various hateful ideologies, continue to point to the presence of extremist narratives in online games, if not their overall prevalence.

As with the questions on swatting and doxing, if adult respondents reported they were exposed to extremist white supremacist ideologies, they were asked to write down their experiences. Our analysis only took into account relevant responses, and we disregarded irrelevant answers in our final total.

It is important to note that within the context of this survey, we are not referring to “white supremacy” as the historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of white dominance and privilege in the U.S. that enables and maintains systemic racism throughout all segments of society. Rather, ADL here uses the term “white supremacy” to specifically refer to the collection of extremist ideologies and groups that undergird the beliefs that white people should dominate in all ways and exercise power over other identities, that there should be a “whites-only” nation, and the express view that “white culture” is superior to other cultures and must be supported, including specifically at the expense of other cultures.9 Here, we specify white supremacist ideology as a symptom and outgrowth of systematic white supremacy.

Our results found that nearly one in ten American adult online multiplayer gamers were exposed to white supremacist ideology in online games. Similar to the 2020 survey, some descriptions of what players experienced in online games are what ADL would call explicit white supremacist ideologies, while others are hateful experiences that do not refer to the explicit beliefs of white supremacists.

Explicit white supremacy:

There were old white men in the voice chat saying how blacks don’t deserve rights like white people.

—19-year-old female, Hispanic/Latinx, disabled, Protestant, and bisexual gamer

Hateful experience:

Recently I had some guy in my League game call everyone on my team the N word just because we weren’t following his [bad] plays. Kept making the same racist remarks throughout the game.

—21-year-old male, South Asian, and heterosexual gamer

Hateful experiences may be motivated by an offending player’s belief in white supremacy or aspects of white supremacist ideology, whose core is antisemitic, anti-Muslim, racist, sexist, and homophobic. But without more information about the motivation of hateful remarks, it is difficult to be sure. We decided to include such experiences in our tally, deferring to lend credence to players’ reported experiences of white supremacy. Furthermore, our total included respondents who opted not to share their experiences due to their sensitive nature.

None of the written responses mentioned recruitment or explicit attempts to indoctrinate players, similar to 2020. However, the responses indicate the continued normalization of white supremacist rhetoric and ideas in online multiplayer games and, more broadly, digital spaces. This is not to say that indoctrination or recruitment into extremist movements using online games is absent, but this survey does not show evidence of such behavior.

Additionally, our survey asked players about their exposure to disinformation or hate targeting the Asian American community and its alleged connection to COVID-19.

Finally, we asked about the prevalence of players’ exposure to conversations on Holocaust denial.

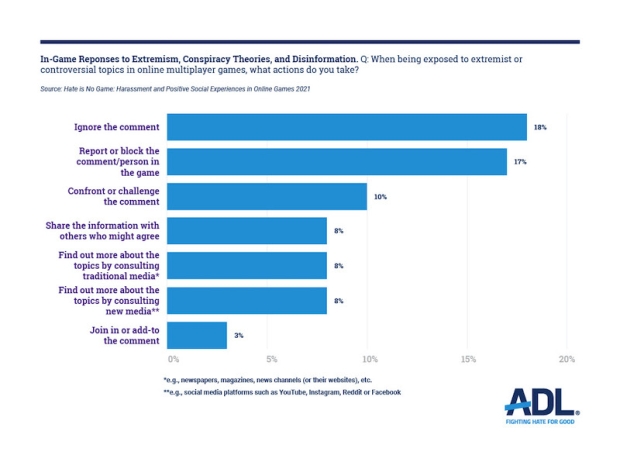

Beyond looking at the prevalence of exposure to extremism and disinformation, our survey also asked players how they responded to these experiences. The most common responses to exposure to these topics were ignoring it, reporting the players involved, or blocking the players. Only 1 in 10 (10%) respondents said that they would confront or challenge these topics when exposed to them.

The Impact of Hate and Harassment on Players

Our survey looked at the impact of harassment in online games on players and how their experiences affected their gameplay. The number of players who quit playing specific online multiplayer games because of harassment increased for the third consecutive year.

The impact of harassment in online games affects how people play. Out of the 81 million American adults who experience harassment in online multiplayer games,10 only 18% stated it had no impact on how they play—meaning harassment shapes the gameplay of over 66 million American adults.

Gamers’ private lives were disrupted by harassment. Nineteen percent reported feeling isolated or alone, 14% reported having depressive or suicidal thoughts, and 13% reported treating other people worse than usual due to the harassment.

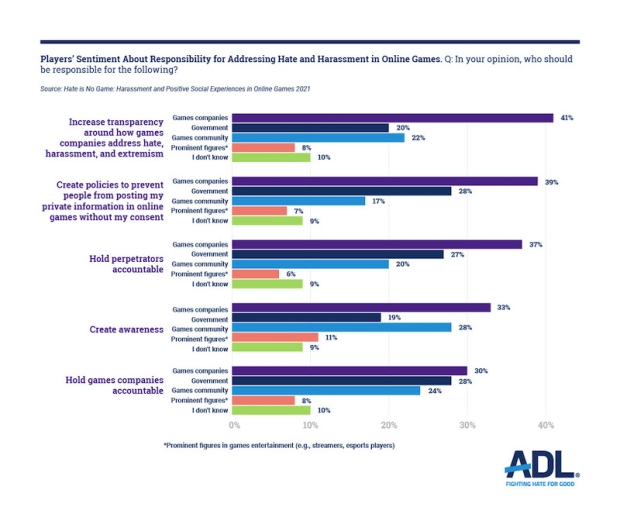

Responsibility for Addressing Hate and Harassment in Online Games

As part of our 2021 survey, we asked gamers for their opinions on different statements regarding how to address hate and harassment in online multiplayer games.

We also asked respondents who they felt should be responsible for addressing hate and harassment in online games.

Recommendations

For the Games Industry

- Release regular and consistent transparency reports regarding hate and harassment. Transparency reports should include data from user-generated identity-based reporting. For example, if players report they were targeted because they were Jewish, that information can be aggregated to become a subjective measure of the scale and nature of antisemitism on a platform. This metric would be useful to researchers and practitioners developing solutions to these problems. In addition to transparency about policies and content moderation, companies should increase transparency related to their products. At present, games companies offer little to no clarity on how they build, improve, and fix the products embedded into their platforms to address hate and harassment. To create transparency reports, companies can consult the Disruption and Harms in Online Gaming Framework, produced by ADL and the Fair Play Alliance, which provides a set of common definitions for hate and harassment in online games.

- Submit to regularly scheduled independent audits. They should allow third-party audits of their work on content moderation on their platforms so the public knows the extent of in-game hate and harassment. Audits would also allow the public to verify that the company followed through on its stated actions and assess the effectiveness of company efforts across time.

- Improve reporting systems and support for targets of harassment in games. Given the prevalence of online hate and harassment, games companies should ensure their platforms offer better and more effective services and tools for individuals facing or fearing an online attack. For example, users should be allowed to flag multiple pieces of content within one report instead of creating a new report for each piece of content. They should be able to block multiple perpetrators of online harassment at once instead of undergoing the laborious process of blocking them individually. IP blocking, preventing users who repeatedly engage in hate and harassment from accessing a game even if they create a new profile, may at times be a valuable tool to protect victims. Games companies should allow individuals facing severe hate and harassment to connect with a live employee for real-time, urgent incidents.

- Address workplace toxicity. Toxic workplaces can be a foundation for toxic games, normalizing harmful behaviors and attitudes online. Games companies must model the kinds of behaviors and communities they want to see on their gaming platforms. Companies can foster healthier cultures through zero-tolerance policies around workplace harassment and regular anti-bias training for all employees.

- Build content moderation tools for in-game voice chat. Abusers, who use voice chat in online games to target individuals, often evade detection because the tools and techniques to detect hate and harassment within games’ voice chat lag behind those that moderate text communication. The games industry, academia, and civil society should develop in-game voice chat content moderation to ensure this goal. Game-specific chat also happens on separate platforms such as Discord and Twitch, so games companies need to coordinate to address off-platform toxicity and harassment.

- Strengthen policies and enforce terms of service. Many companies that created the games included in this survey have Codes of Conduct or Terms of Use that prohibit hate or harassment, but they are vague in the ways they describe protected groups and violative conduct. We recommend companies specify protected categories (including gender, gender identity, race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, ability status) in their Terms of Use and explicitly prohibit doxing and swatting. In developing these Terms of Use, we advise games companies to consult with individuals and organizations representing groups that experience high rates of harassment.

- Implement industry-wide design practices to better address white supremacy. Additionally, the games industry should incorporate anti-hate-by-design practices to mitigate the exploitation of their platforms to spread extremist disinformation, invest in strategies to off-ramp those on the path to radicalization, and work with civil society to mitigate the threat. Just as privacy-by-design has been promoted with some notable success, “anti-hate by design” must be promoted and widely incorporated, and made a fundamental consumer expectation.

- Include metrics on in-game extremism and toxicity in the Entertainment Software Rating Board’s rating systems of games. The ESRB rating system is effective at providing players, especially parents whose children play games, with information about a game’s content and its appropriateness for different age groups. Although games companies often inform players that the gameplay experience may depend on the behavior of other players, there are no audits of toxicity and extremism in online games. Such audits would allow companies to include information and metrics about toxicity and extremism in their ratings, to allow players or parents of players to make informed decisions about potential exposure to harmful content or harassment.

For Civil Society

- Support the research of games scholars and practitioners. Many games scholars and practitioners in academia have spent decades studying games’ potential for both good and harm. We encourage civil society organizations to engage seriously with these researchers and expand knowledge on the impact of games. Civil society organizations should familiarize themselves with academic research on games and partner with researchers to expand understanding of the risks and benefits of online games and make their findings accessible to the broader public. While academic research on toxicity and extremism is robust and evolving, civil society organizations can support further investigation into potential solutions for developing next generation game design, technologies, and social norms.

- Center the voices of marginalized people, including players and developers, to bring to the foreground the experiences of those most targeted by identity-based hate and harassment. Along with companies hiring diverse teams, to expand the range of perspectives in game design advocacy organizations should amplify the concerns of marginalized communities, who are experts in the issues that affect them.

- Support educational efforts for young gamers and the adults in their lives. Research on youth and social media offers models for addressing hate and toxicity online, including designing better tools and interventions. Peer education and support are critical to teaching youth to navigate digital tools and worlds, along with educating parents and other adults.

For Government

- Prioritize regulations and reform. Platforms play an active role by providing the means for transmitting hateful content and, more passively, enabling the incitement of violence, political polarization, spreading of conspiracies, and facilitation of discrimination and harassment. Unlike traditional publishers, technology companies are largely shielded from legal liability for even unlawful third-party content due to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA 230). Section 230 was also intended to incentivize content moderation against both unlawful and “lawful but awful” content. But self-regulation has been largely unsuccessful.

Congress must carefully reform, not eliminate, CDA 230 to hold social media platforms accountable for their role in fomenting hate. At the same time, reform must prioritize both civil rights and civil liberties and avoid silencing the very voices we should be seeking to protect. Federal and state authorities must also pass laws and undertake other approaches that require regular reporting, increased transparency and independent audits regarding content moderation, algorithms and engagement features. - Strengthen laws against perpetrators of online hate. Hate and harassment exists both online and on the ground but our laws have not kept up. Many forms of severe online misconduct, like doxing and swatting, are inconsistently covered by cyber harassment and stalking laws. Legislators should pass laws that hold perpetrators of severe online hate and harassment accountable for their offenses, at both the state and federal level. Congress can lead the fight against hate in online games by increasing protections for targets and requiring more transparency and accountability from social media and games companies. ADL’s Backspace Hate initiative raises awareness and works at the state and federal level to fill the gaps and loopholes in our legal system regarding digital abuse.

- Improve training for law enforcement. Law enforcement is a critical first responder to online hate, especially when users feel they are in imminent physical danger. Increasing resources for these departments can help them investigate and prosecute cyberharassment cases effectively. The training and resources should also include ways in which law enforcement can refer people to non-legal support if online harassment cannot be addressed through legal remedies.

For Caregivers and Educators

- Learn about and make deliberate, proactive choices about safety controls. Less than 40% of parents or guardians reported having implemented the safety controls in online multiplayer games that were included in this survey. While not every adult may want to limit how young people in their lives communicate in online games, adults should make conscious decisions as to whether to allow in-game communications or block young players from having conversations with strangers via voice or text chat. They should also learn how to implement safety controls and turn them on, especially for younger gamers.

- Demand games companies improve parental safety controls and education. Safety controls need to be transparent and user-friendly for parents and other adults who may not know much about online games or toxicity. These demands should include safety by default, such as parental accounts accompanying users under a certain age, and disallowing messages from strangers or access to chat unless adults opt-in. Parental controls should also enable approval to add friends or contacts for young users.

- Familiarize yourself with the games young people in your life play and have meaningful conversations about their experiences in online games. Less than half of teenage gamers ADL surveyed talk to the adults in their lives about their experiences in online multiplayer games. An adult would want to know who young people are interacting with at school, so adults—whether parents, extended family, teachers, counselors or others—should exhibit a similar level of concern for them in playing online games. Spending time playing games with young people can increase adult understanding of both the enjoyment and harms of online games.

Appendix: Additional Results

Young People (13-17)

Harassment by Game and Delivery Channel

At least 62% of young gamers experienced harassment in every game we included in this survey.

Our survey also examined the delivery channels within an online game where young people reported experiencing harassment.

The vast majority of young gamers said they either play online games by themselves (96%) or with friends (96%) most of the time.

Adults (18-45)

Positive Social Experiences by Game

At least 87% of players in every game of this report had some positive in-game social experiences.

The games where players reported the most positive social experiences in 2020 showed a decline in such experiences in 2021. World of Warcraft went from 98% in 2020 to 92% in 2021, and Counterstrike: Global Offensive went from 96% to 90%, a decrease of six points in both cases. The vehicular soccer game Rocket League went from 96% in 2020 to 89% in 2021, a drop of seven points.

Over 85% of players had positive social experiences in each of the seven online multiplayer shooter games (Apex Legends, Call of Duty, Valorant, Fortnite, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, PUBG: Battlegrounds and Overwatch) of various types and structures, continuing the trend we have seen across all three years of this survey. Despite public consternation about these games ' relationships to gun violence and morality, a significant number of players had meaningful positive social experiences in online multiplayer shooters. They make friends, learn about themselves and others, and find community.

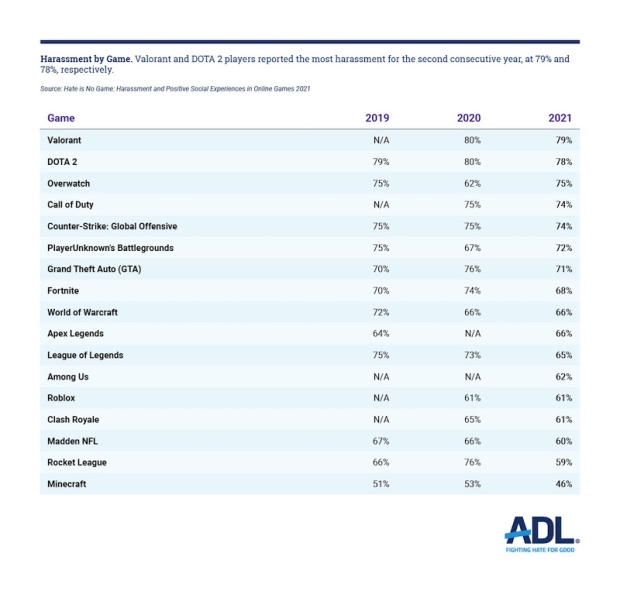

Harassment by Game

Our study looked at players’ experiences of harassment in several popular and prominent online multiplayer games that ADL and Newzoo chose to analyze. For the third year in a row, harassment is common in online multiplayer games, regardless of genre. This year’s list included shooters and multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) games within sports, adventure, and role-playing. Several games were omitted from this year’s survey that appeared last year due to shifts in popularity, and a few new games were added, such as Among Us, due to overwhelming popularity.

At least 46% of players experienced harassment in each game included in this survey, with Minecraft as the game where players reported the least harassment (46%). The game with the second least amount of harassment this year was Rocket League, which had the most significant decrease in harassment: Fifty-nine percent of players reported experiencing harassment in 2021 compared to 75% in 2020, a difference of 16 points. Another notable drop in harassment occurred in the shooter Fortnite—68% of players reported experiencing harassment in Fortnite in 2021, whereas 74% reported harassment in 2020, a six-point decrease.

Valorant and DOTA 2 are the games where players reported the most harassment for the second consecutive year.

Seventy-five percent of players experienced harassment in the shooter Overwatch which had the largest year-over-year increase in harassment—a 13-point increase from 62% the previous year.

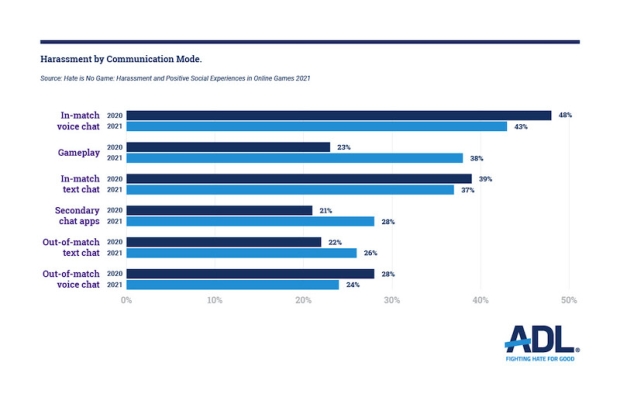

Harassment by Delivery Channel

We asked players about the delivery channels they used to learn more about the environments in which online multiplayer gamers experienced harassment. More players reported harassment through voice chats than text chats for both in-game and out-of-game channels.

The Impact of Hate and Harassment on Players

The games that most players said have the most hostile environments were Valorant (42%) followed by Call of Duty (42%), DOTA 2 (37%), PlayerUnknown BattleGrounds (35%), Fortnite (34%) and League of Legends (34%). Players either exercised more caution or stopped playing each of these games as a result of harassment.

Acknowledgments

ADL would like to thank Professor Katie Salen of the University of California at Irvine and the team at Raising Good Gamers, a nonprofit that brings together young people, educators, researchers, and games industry executives to improve the climate and design of online games, for their help in revising questions in this survey for young gamers. We would also like to thank Professor Constance Steinkuehler of the University of California at Irvine for her help crafting this survey’s recommendations.

Endnotes

- When we say players “experienced” hate, harassment, or positive social interactions, the time period at issue is within the past six months directly preceding the date on which they took our survey. Surveys were conducted from June 7 to June 25, 2021. Nor does our use of the past tense—“experienced”—mean these players are no longer targets. In fact, our findings show the opposite is likely true.

- Responses from young gamers first incorporate some answers from the adults in their lives. Then the adult allowed the minor respondent to answer the rest of the questions. The questions posed solely to adult respondents do not include questions about topics they discussed with gamers under age 18.

- Defined as harassment that occurs over multiple game sessions or a longer period of time.

- Entertainment Software Association, “2021 Essential Facts About the Video Game Industry”

- Newzoo, “Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”

- Calculated by Newzoo.

- Population estimates calculated by Newzoo.

- Calculated by Newzoo.

- https://www.adl.org/resources/glossary-terms/white-supremacy

- Calculated by Newzoo.

Donor Recognition

This work is made possible in part by the generous support of:

Anonymous

Anonymous

The Robert Belfer Family

Dr. Georgette Bennett

Catena Foundation

Craig Newmark Philanthropies

Crown Family Philanthropies

The David Tepper Charitable Foundation, Inc.

Electronic Arts

The Grove Foundation

Joyce and Irving Goldman Family Foundation

Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation

Walter & Elise Haas Fund

One8 Foundation

John Pritzker Family Fund

Qatalyst Partners

Quadrivium Foundation

Righteous Persons Foundation

Riot Games

Amy and Robert Stavis

Zegar Family Foundation