Join ADL

in urging Congress to support the Countering Antisemitism Act

Introduction

How do we reduce antisemitism? How do we lessen the conditions required for the normalization of antisemitism? And, among those already at least somewhat neutral, how do we cultivate a disposition of allyship?

Established by ADL in 2022, the Center for Antisemitism Research (CAR) is designed to answer those questions. Along with its network of academic partners and research fellows at universities and colleges around the world, CAR conducts qualitative and quantitative investigations to identify the primary factors underpinning antisemitism and assess interventions designed to ameliorate them. The interventions inform ADL’s development and continued evaluation of educational resources and programming, anti-hate messaging campaigns, and policy recommendations.

By developing and scaling evidence-based interventions that have proven to reliably address the factors underpinning antisemitism, ADL and partner organizations can effectively reduce antisemitism. This first publication in the new What Works series seeks to communicate to our audiences the insights from the most promising interventions assessed to date and to outline the subsequent steps being taken to evaluate the scalability and durability of each intervention.

This report series is underpinned by the aspiration that it will motivate key partners and community leaders to engage with the suggested interventions and utilize them to shape their own messaging, campaigning, and intervention strategies.

Part 1: How To Fight Antisemitism

How do you fight antisemitism? For a few bad actors, the answer to that question may be different than for large populations. On a societal level, the driving question is more like: what are the key factors that we need to alter in order to reduce endorsements of anti-Jewish tropes and lessen a disposition toward anti-Jewish hostility? Put another way, what explains why people are antisemitic and, critically, what factors can drive it down?

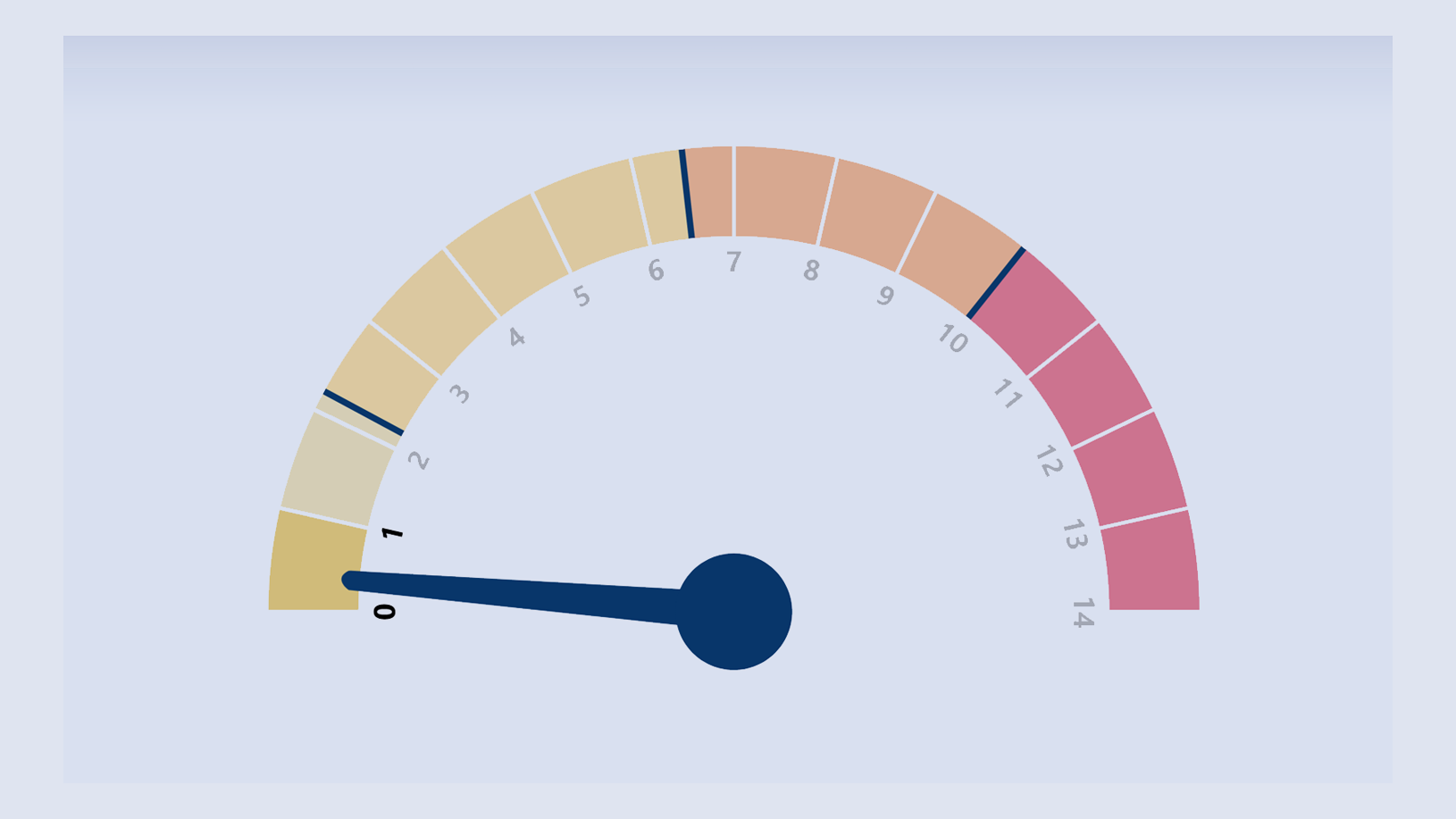

Starting from existing theories and previous empirical research, CAR researchers have run several studies from 2022 to 2024 to isolate and identify the criteria necessary for the production of antisemitism. Through this research, the team has identified several cross-demographic levers that can be managed to attenuate anti-Jewish sentiment across society. These levers include efforts to affect people’s social surrounding, level of belief in conspiracy theories, agreement with an oppressor versus oppressed ideology and social dominance orientation; awareness of Zionism; and perceptions of the seriousness of anti-Jewish prejudice. These factors are tightly related to antisemitism and, when added together, are associated with an increase in the probability someone will agree with anti-Jewish tropes and anti-Israel positions.

The above visualization highlights how attenuating certain factors produce a range of changes to belief in anti-Jewish tropes. Anti-Jewish tropes make up the ADL Index, first developed by researchers at UC Berkeley in the early 1960s and elaborated upon by the Center for Antisemitism Research since 2022. They are used as an attitudinal measure to assess overt anti-Jewish sentiment. Traditionally, ADL has counted agreement with a majority of tropes as a signal of substantive antisemitic beliefs. Currently, researchers rely more on predictive probabilities as demonstrated in this tool.

That said, what is NOT a useful lever is also sometimes as important as what actually is predictive. In this case, for example, sharing an aspiration for Palestinian sovereignty barely moves the needle, indicating that many people who are not antisemitic share that desire.

Part 2: Narratives to Reduce Antisemitism | Discrimination as Treatment

CAR Research Fellows: David Broockman, PhD (UC Berkeley) and Josh Kalla, PhD (Yale)

Antisemitism and other forms of prejudice are on the rise worldwide. Our field research on “deep canvassing” has found that sharing narratives about outgroup members can durably reduce multiple forms of prejudice.

These results are noteworthy: most interventions to reduce prejudice have limited effects that decay rapidly. However, our previous research did not investigate which narratives are most effective (e.g., about discrimination an outgroup faces, about their contributions to their communities, etc.), nor has our previous research investigated antisemitism.

Partnering with ADL, we recently investigated which narratives most effectively reduce prejudice, and whether these narratives would effectively reduce antisemitism. We began by reviewing the stories canvassers had shared as part of implementing our prior “deep canvassing” studies. This review surfaced several common narrative paradigms (described below). We then conducted a very large online survey experiment (n = 22,940) to test whether each of these eight narrative types would successfully reduce prejudice against each of four groups: Jewish-Americans, Chinese-Americans, undocumented immigrants, and transgender people.

To conduct the experiments, we first randomly assigned respondents to one of these four groups. Respondents were also randomly assigned to one of the eight narrative types, or to a control group. Those in the narrative groups watched a two-minute video sharing a narrative corresponding with the narrative they were randomly assigned about the outgroup they were randomly assigned. Finally, we asked our primary outcome measures to test whether the videos reduced prejudice towards the group; e.g., “I would have no problem living in areas where [outgroups] live”, a feeling thermometer towards the outgroup, etc. Our primary outcome is an index combining all of these variables into a single number which captures overall positive versus prejudiced feelings towards the outgroup.

The list below gives the eight narrative types. The videos which delivered the narratives were all around two minutes long, featured the same actor, and all told similar stories about Maya, a waitress. The videos were adapted to signal Maya’s specific outgroup (Jewish-American, Chinese-American, undocumented immigrant, or transgender). Linked below are examples of the “Jewish videos”.

- Suffering: A bad thing happens to an outgroup individual (Maya), but it is not made explicit that it is because of discrimination.

- Suffering + due to discrimination: A bad thing happens to Maya, and it is clear that it is because of discrimination due to her outgroup membership.

- Economic achievement: Maya is successful economically, working her way up from a low-income job to a higher income job.

- Economic achievement + policy: Maya is successful economically and this success is due to an important pro-outgroup policy. For example, in the undocumented immigrant case, Maya is able to become a manager of a franchise because she was able to apply for work authorization through DACA.

- Economic achievement + public good: Maya is successful economically and uses that success to give back to her community by volunteering and donating to the local food bank.

- Achievement + high cultural assimilation: Maya is economically successful. She also has a male spouse and two children. There is additional information that signals Maya is culturally normative by American standards. For example, in the Jewish message, Maya puts up Christmas lights because her neighbors all do, even though she is Jewish.

- Achievement + low cultural assimilation: Maya is economically successful. She has a spouse and two children. There is information that signals Maya is not culturally normative by American standards. For example, in the Jewish message, Maya gives her children stereotypically Jewish names (Shira and Moshe), sends them to Jewish day school, and reads bedtime stories to them in Hebrew.

- Bipartisanship: Our hired actor conveys that both Democrats and Republicans (specifically Biden and Trump) support the relevant outgroup. We then used real video clips of Trump and Biden making pro-outgroup statements. For example, both Biden and Trump have publicly condemned antisemitism.

- Control: This is the baseline group for our statistical comparisons. In this video, our hired actor relays a story about how voting by mail made casting a ballot more accessible to his family. None of the outgroups are mentioned.

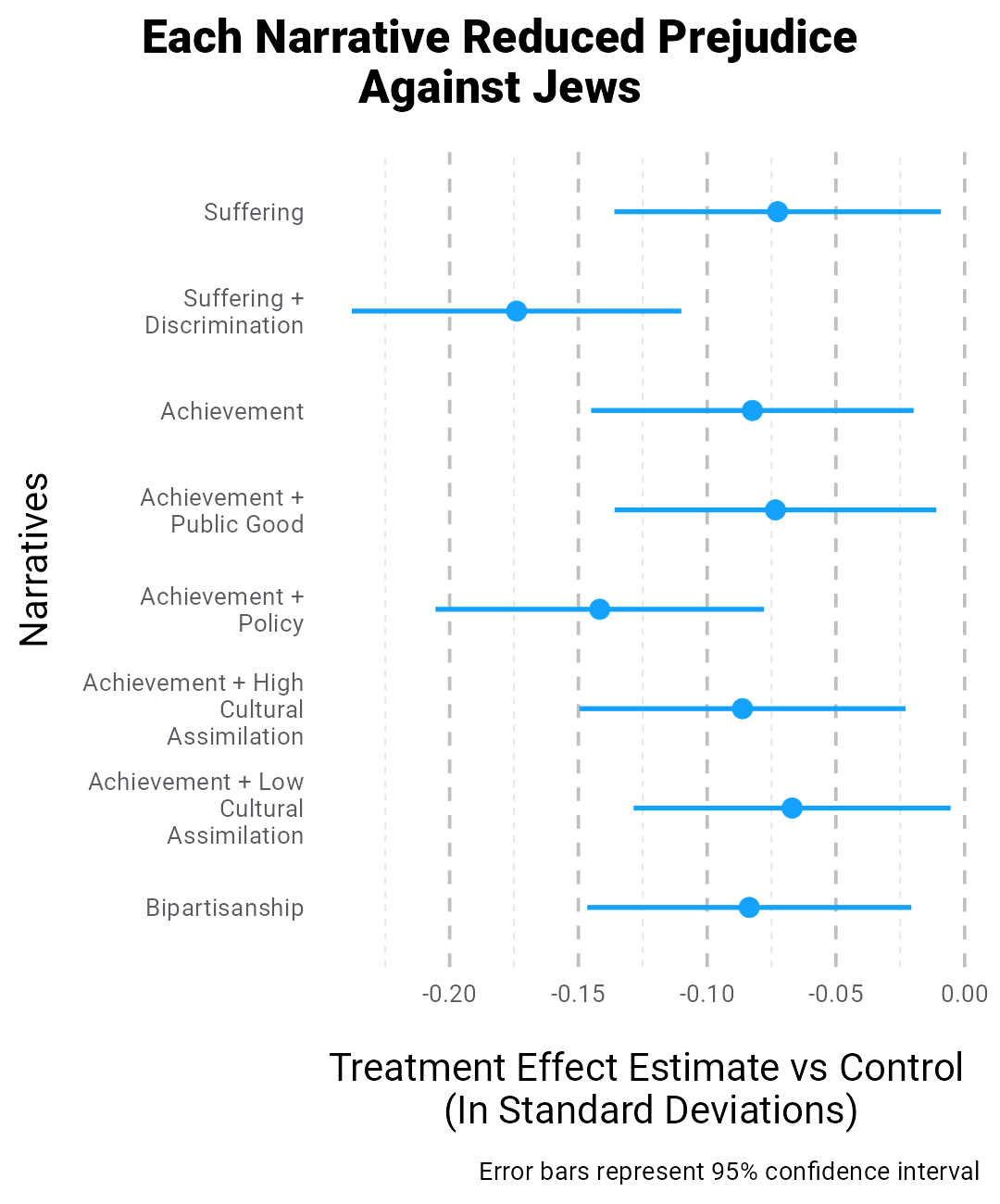

The effects of each narrative are presented below. Negative numbers correspond with larger effects in reducing prejudice.

We randomly assigned whether the videos ended with a clear conclusion. Half of the time, the videos would end with a statement that summarized the issue and presented a policy solution that could help prevent future discrimination. For example, in the Jewish message, this statement was, “Companies should give their employees training on how to avoid discriminating against Jewish-Americans so that people like Maya can succeed without discrimination standing in their way.” In the undocumented immigrant message, this statement was, “We should allow people like Maya whose parents illegally brought them here as children to become US citizens.”

There are three key results from this experiment:

- We find that all of the video narratives successfully decreased prejudice relative to the control group. The narratives also seem to broadly work across the four outgroups.

- We find that two particular narratives – suffering + due to discrimination and economic achievement + policy – appear to be particularly effective at reducing prejudice.

- We find that adding the clear and explicit conclusion increased the efficacy of the video narrative at reducing prejudice.

Part 3: Narratives to Reduce Antisemitism: Humor as Treatment

CAR Research Fellows: Catie Bailard, PhD (GWU), Andrew Thompson, PhD (GWU), and Rebekah Tromble, PhD (GWU)

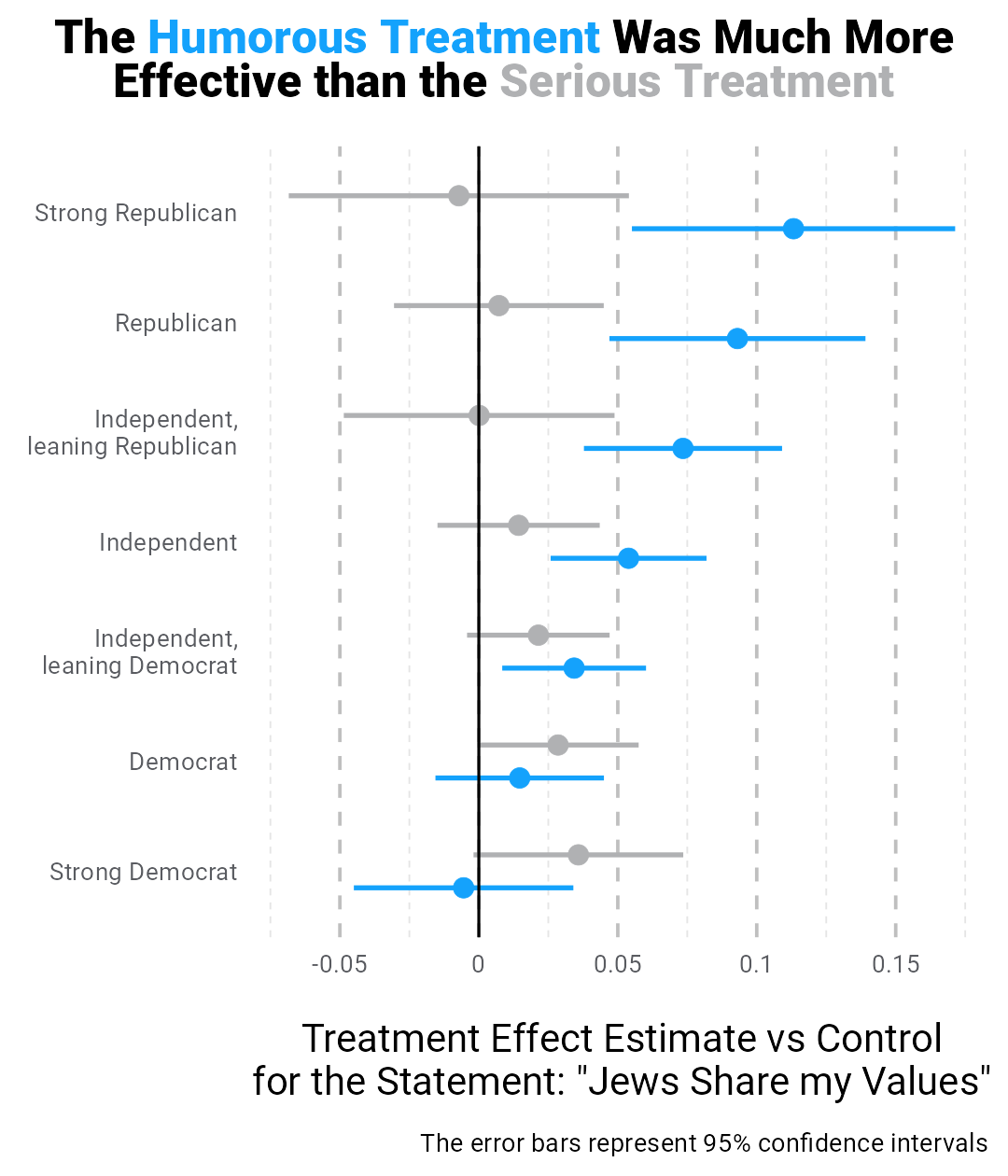

Partnering with ADL, we investigated whether humorous perspective-getting narratives could durably reduce antisemitism among a more conservative audience. Humor among more conservative Americans functions not just as a social lubricant but as a way to camouflage discomfort with personal positions that self-consciously may be seen as counter cultural or even radical. We hypothesized that leveraging humor may better address this audience and its specific rhetorical and cultural style.

We conducted a survey experiment embedded with videos from two different comedians, both told the same story of a personal experience with antisemitism, one was told humorously, the other was not. 3,144 subjects were randomly assigned to one of three treatment arms, 1/3 were assigned to a control, 1/3 to a humorous video treatment, 1/3 to a serious version of the same narrative.

We found that:

- Both humorous and serious versions of the narrative increase general feelings of sympathy toward Jews

- How funny respondents found the humorous narrative versions significantly moderated their effects

- Relative to a serious version of the narrative, the humorous versions produced stronger effects among conservative Americans, especially related to perceptions that “Jews share my values”

- Relative to a serious version of the narrative, the humorous versions produced no statistical significance, though, when it came to lowering pre-test feeling thermometer scores.

Conclusion

In the first half of 2024, CAR and its research partners gained valuable insights into several viable avenues for developing durable and scalable interventions. Foremost, having been explored by two fellowship teams, perspective-getting narratives have been identified as a promising tool to reduce prejudice, including antisemitism. While assessments of the interventions continue to be underway, the potential prejudice-reducing applications of perspective-getting narratives may be abundant, ranging from possible use within education spaces to marketing and campaigning strategies.

The research - specifically the humor-based treatment, which was most effective among conservatives - has also highlighted the importance of carefully tailoring specific perspective-getting narratives to different subgroups to maximize the efficacy of the intervention. Leveraging these findings and an existing bank of data-driven insights, CAR is continuing to work independently and with its affiliates to craft optimal awareness-raising and educational interventions that can reliably reduce antisemitic attitudes.

About CAR

Center for Antisemitism Research (CAR) works to understand and counter antisemitism by ensuring that decision-makers are informed by scholarly investigation and empirical evidence. Along with its network

of academic partners and research fellows at universities and colleges around the world, CAR conducts qualitative and quantitative research to identify the primary factors underpinning antisemitism and assess interventions designed to ameliorate them. The interventions inform ADL’s development and continued evaluation of educational resources and programming, anti-hate campaigns and policy recommendations. CAR’s rigor guides ADL’s work and advocacy while advancing the global field of antisemitism research.

Donor Recognition

The work of the ADL Center for Antisemitism Research is made possible by the generous support of:

Anonymous

ADL Lewy Family Institute for Combating Antisemitism

The Crimson Lion/Lavine Family Foundation

David Berg Foundation

Lillian and Larry Goodman Foundation

Diane & Guilford Glazer Foundation

The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation

Erwin Rautenberg Foundation

ADL gratefully acknowledges all of the individual, corporate and foundation supporters who make our work possible.