Download the full PDF report:

A report from the Center on Extremism

Executive Summary

White supremacists in the United States have experienced a resurgence in the past three years, driven in large part by the rise of the alt right.

- The white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 11-12, 2017, attracted some 600 extremists from around the country and ended in deadly violence. These shocking events served as a wake-up call for many Americans about a resurgent white supremacist movement in the United States.

- Modern white supremacist ideology is centered on the assertion that the white race is in danger of extinction, drowned by a rising tide of non-white people who are controlled and manipulated by Jews. White supremacists believe that almost any action is justified if it will help “save” the white race.

- The white supremacist resurgence is driven in large part by the rise of the alt right, the newest segment of the white supremacist movement. Youth-oriented and overwhelmingly male, the alt right has provided new energy to the movement, but has also been a destabilizing force, much as racist skinheads were to the movement in the 1980s and early 1990s.

- The alt right has a white supremacist ideology heavily influenced by a number of sources, including paleoconservatism, neo-Nazism and fascism, identitarianism, renegade conservatives and right-wing conspiracy theorists. The alt right also possesses its own distinct subculture, derived especially from the misogynists of the so-called “manosphere” and from online discussion forums such as 4chan, 8chan and Reddit.

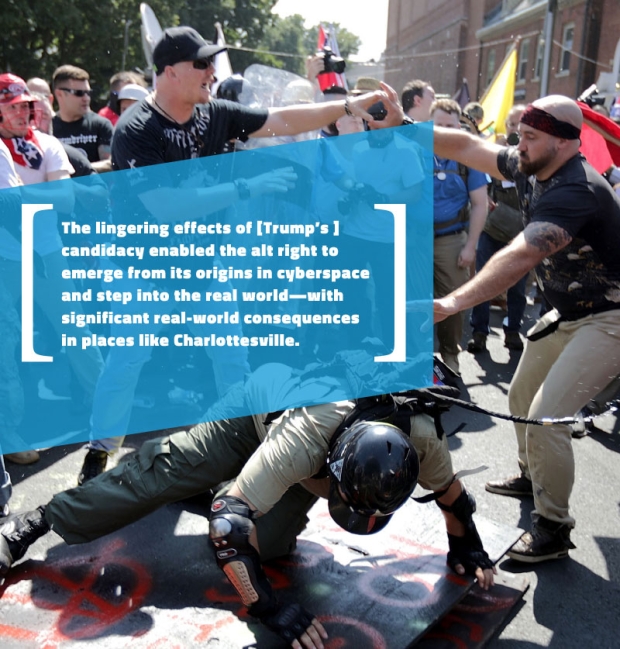

- Though aspects of the alt right date back to 2008, it was Donald Trump’s entry in 2015 into the 2016 presidential race that really energized the alt right and caused it to become highly active in support of Trump. This activism drew media attention that provided publicity for the alt right and allowed it to grow further. The alt right interpreted Trump’s success at the polls in November 2016 as a success for their own movement as well.

- After the election, the alt right moved from online activism into the real world, forming real-world groups and organizations and engaging in tactics such as targeting college campuses. The alt right also expanded its online propaganda efforts, especially through podcasting.

- As the alt right received increased media scrutiny—in large part due to its own actions, such as the violence at Charlottesville—the alt right experienced dissension and disunity in its own right, including the departure of many extremists who did not advocate explicit white supremacy (the so-called “alt lite”). The backlash against the alt right after Charlottesville hurt many of its leading spokespeople but has not resulted, as some have claimed, in a decline in the movement as a whole.

- Other white supremacists—neo-Nazis, traditional white supremacists, racist skinheads, white supremacist religious sects, and white supremacist prison gangs—have also continued their activities. Some white supremacists, such as neo-Nazis, seem to have been buoyed by the alt right to some extent, while others— most notably racist skinheads—may experience a loss of potential recruits at the hands of the alt right.

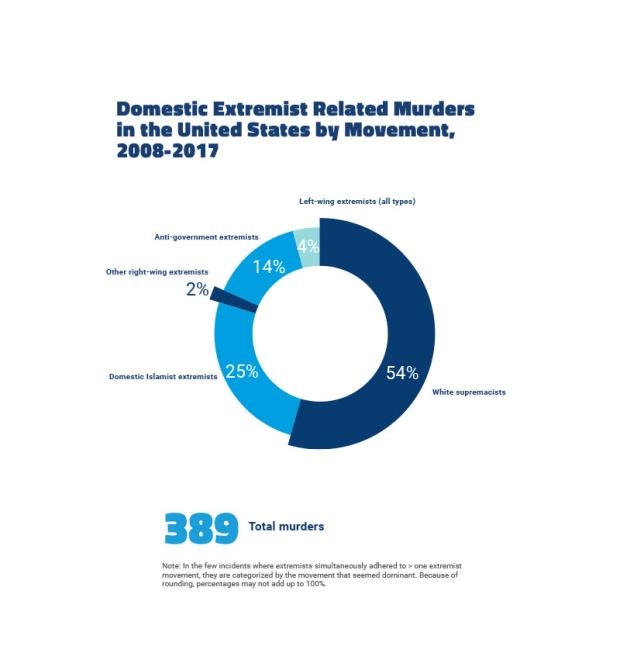

- Violence and crime represent the most serious problems emanating from the white supremacist movement. White supremacists have killed more people in recent years than any other type of domestic extremist (54% of all domestic extremist-related murders in the past 10 years). They are also a troubling source of domestic terror incidents (including 13 plots or attacks within the past five years).

- Murders and terror plots represent only the tip of the iceberg of white supremacist violence, as there are many more incidents involving less serious crimes, including attempted murders, assaults, weapons and explosives violations, and more. In addition, white supremacists engage in a lot of non-ideological crime, including crimes of violence against women and drug-related crimes.

Download Full PDF Report

One Year Ago - A Death in Charlottesville

Months of nationwide white supremacist activity culminated in August 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, where hundreds of hardcore racists gathered in a highly publicized two-day protest they called “Unite the Right.” On the first night, close to 200 marchers, mostly from the alt right segment of the white supremacist movement, assembled with tiki torches on the campus of the University of Virginia, chanting racist and anti-Semitic slogans and fighting with a small group of anti-racist counter-protesters.

The next day, August 12, was the largest public rally of white supremacists in more than a decade, with more than 500 white supremacists on hand. The many alt right activists were joined by a variety of other white supremacist groups: Neo-Nazis from the National Socialist Movement, Vanguard America and the Traditionalist Worker Party; Klan members from the Rebel Brigade Knights, the Global Crusader Knights, and the Confederate White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan; racist skinheads from the Hammerskins; Christian Identity adherents from Christogenea; neo-Confederates from the League of the South; Odinists from the Asatru Folk Assembly; and many others. Almost every segment of the white supremacist movement was represented in Charlottesville that day.

As the racists made their way across town towards their planned rally location at Emancipation Park, they repeatedly encountered anti-racist protesters. It did not take long for violence to ensue. One African-American man was beaten in a parking garage by a group of white supremacists with poles and pipes.

Other white supremacists confronted and attacked counter-protesters in various locations—and were occasionally attacked by them as well, though most of the violence that day originated with the white supremacists. Though there was a heavy law enforcement presence, the police inexplicably took a hands-off approach.

Eventually, the violence and disorder escalated to a point where authorities declared the gathering unlawful and began to disperse white supremacists and counter-protesters alike. Some white supremacists made their way to an alternate rally location while others slowly walked back to their cars or hotels.

The violence of the day, however, was not yet over. In the afternoon, a young alt right white supremacist from Ohio, James Alex Fields, Jr., apparently deliberately drove his vehicle into a crowd of counter-protesters, throwing some into the air. The attack injured 19 people and killed one woman, Heather Heyer, who had come out to protest the white supremacists. Fields was subsequently charged with first-degree murder and other state and federal charges related to the attack, including federal hate crime charges. The nation was shocked by the violence and by the widely-covered gathering of so many white supremacists. The event served as a wake-up call for many Americans, who became newly aware of the country’s resurgent white supremacist problem, a movement active, angry, and flush with young new followers.

The White House’s reaction to events at Charlottesville only added to the controversy. Though many politicians from both parties condemned the white supremacist violence, President Donald Trump’s August 12 statement condemned hate, bigotry and violence—not on the part of white supremacists but “on many sides, on many sides.” According to the New York Times, White House chief strategist Stephen Bannon had urged Trump not to criticize the extremists at Charlottesville too harshly, “for fear of antagonizing a small but energetic part of his base.”

Two days later, Trump issued a second statement more explicitly mentioning the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, white supremacists “and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans.” However, the next day, in response to a reporter’s question, Trump once again claimed that there was “blame on both sides” and “very fine people on both sides.” He also claimed there was violence from the “alt left,” though no such entity actually exists.

Both the Charlottesville violence and the White House reaction to it illustrate the strange and frustrating landscape of white supremacy in the United States today, a landscape not only shaped and textured by the rise of a new generation of white supremacists who differ in significant ways from their older counterparts, but also inextricably connected in numerous ways to the Trump campaign and presidency.

This is not to say—as many on the left vocally assert—that Donald Trump is himself a white supremacist, or that he has surrounded himself with them, though journalists have demonstrated the problematic histories and ties of many administration appointees. But it is undeniable that Trump’s campaign, even if unintentionally, helped the alt right cohere and grow, just as it is equally obvious that, following his election, the lingering effects of his candidacy enabled the alt right to emerge from its origins in cyberspace and step into the real world—with significant real-world consequences in places like Charlottesville.

White Supremacy - The Haters and the Hated

The problem of white supremacy goes beyond mere racism or bigotry, because white supremacy is more than a collection of prejudices: it is a complete ideology or worldview that can be as deeply-seated as strongly held religious beliefs. Many historians suggest white supremacist ideology in the United States originally emerged in the antebellum South as a way

for white Southerners to respond to abolitionist attacks on slavery.

In the intervening years, white supremacy has expanded to include many additional elements, such as an emphasis on anti-Semitism and nativism. During that time, different variations and versions of white supremacy have also evolved. White supremacists themselves typically no longer use the term, as they once proudly did, but tend instead to prefer various euphemisms, ranging from “white nationalist” to “white separatist” to “race realist” or “identitarian.” Even in the face of these complexities, it is still possible to arrive at a useful working definition of the concept of white supremacy.

Through the Civil Rights era, white supremacist ideology focused on the perceived need to maintain the dominance of the white race in the United States. After the Civil Rights era, white supremacists realized their views had become increasingly unpopular in American society and their ideology adapted to the new reality.

Today, white supremacist ideology, no matter what version or variation, tends to focus on the notion that the white race itself is now threatened with imminent extinction, doomed—unless white supremacists take action—by a rising tide of people of color who are being controlled and manipulated by Jews. White supremacists promote the concept of ongoing or future “white genocide” in their efforts to wake white people up to their ostensible dire racial future. The popular white supremacist slogan known as the “Fourteen Words” reflects these beliefs and holds center stage: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” Secure a future, as white supremacists see it, in the face of the efforts of their enemies’ to destroy it.

Jews

White supremacists have a reservoir of loathing deep enough to accommodate a wide range of hatreds, but they reserve a special status among their enemies for Jews. And although white supremacists fear and despise people of most other races, most also assume whites are far superior to people of other backgrounds, which raises questions about the ability of those ostensibly inferior races truly to threaten white dominance or survival. This, for white supremacists, is where the Jews come in. White supremacists portray Jews as intelligent, but also as loathsome parasites (using anti-Semitic stereotypes such as the “Happy Merchant” meme to convey this notion) who control and manipulate the actions of non-white races to the advantage of the Jews and the detriment of the white race.

This is the longstanding anti-Semitic notion of the international Jewish conspiracy, a theme no less powerful in the days of the alt right than it was in Tsarist Russia. “Jews are the eternal enemy of the White race,” asserted one poster to the white supremacist discussion forum Stormfront this past May, “and need to be treated as such. There are no good Jews, they are all traitors and loyal only to their race…Any action that White people take to get rid of the Jews is strictly self-defense, in much the same way that you would try to destroy a poisonous snake that is threatening your safety. The Jews are poisonous to the moral fabric of White society.” The poster went on to characterize Hitler as too kind and generous in his actions toward the Jews.

Jews, according to white supremacists, are the great puppet-masters. They control the media, they control the Internet, they control everything required to manipulate entire peoples for their benefit. White supremacists typically believe that Jews or Jewish machinations are behind almost everything they despise or fear, including liberalism, immigration, and multiculturalism. Even psychiatry, as one white supremacist suggested on Twitter in March 2018, “is a Jewish communist weapon, and World Jewry knows the value of using the mental health system as a weapon against people.”

African-Americans

If Jews are the puppeteers in the white supremacist worldview, non-white peoples are the puppets. In particular, white supremacists in the United States focus on African-Americans as a racial enemy secondary only to Jews. Using centuries-old stereotypes and racist attacks portraying African-Americans as unintelligent, primitive and savage, white supremacists claim that black people are the main tools used in Jewish efforts to weaken or attack the white race.

“Larceny & mayhem are in the DNA” of blacks, claimed a member of the League of the South on Twitter recently. The concocted issue of “black-on-white crime” is one of the major propaganda tools utilized by white supremacists for recruitment. “You see the crimes against our people every day,” claims the website of the neo-Nazi Vanguard America, referencing people being murdered by “bloodthirsty negroes” and “Judges protecting the rapists of our girls.” The government, claims the neo-Nazi group, does nothing to protect whites, because “the childraping [sic] politicians and their Jewish puppet masters are complicit in these crimes against our race.”

Multi-racial couples/families

White supremacists view multi-racial couples and families as a particularly heinous crime and offense—one that has spurred deadly hate crimes by white supremacists—in part because white supremacists view such couples and families as visual evidence of the future extinction of the white race.

White supremacists commonly claim that Jews attempt to harness the “savage lust” they attribute to most non-white peoples possess in order to pollute, weaken and eventually end the white race itself. “I think it is impossible to not notice how much the Jew media machine have been pushing White males with Black females,” observed long-time white supremacist Robert Ransdell on Stormfront last December (Ransdell has since died in an auto accident). He also claimed that the Jews had “pushed” the “Black male with White female” angle for decades. Why would they do this? Another Stormfronter had the clear answer: “They try to teach our children that mud is beautiful. They want to make certain that no more white children are born on this earth.”

Latinos and Immigrants

Latinos—typically perceived by white supremacists as immigrants regardless of how many generations they or their ancestors may have been in the United States—increasingly attract white supremacist attention and hatred. American white supremacists are well aware of demographic changes in the United States, which they typically portray as an “invasion.”

“White man,” proclaimed Michael Hill, the League of the South leader, on Twitter in May 2018, “your countries are being purposely overrun with Third World savages who intend to replace you and take your wealth and women. What are you doing to stop this invasion?”

Muslims

Muslims, and people who are perceived to be Muslims, have increasingly become a target of white supremacists who see the religion as “foreign” and as an existential threat to Western civilization. The fact that many Muslims in the United States are non-white or may be immigrants adds to white supremacist hatred.

American white supremacists applaud European far right activists’ efforts to demonize Muslim refugees and immigrants and to portray Europe as being invaded and brought low by Muslim immigration. American white supremacists claim the United States will suffer a similar fate unless Muslims are excluded. Needless to say, white supremacists also embrace the anti-Muslim conspiracy theories promoted by American Islamophobes.

As a result, anti-Muslim themes frequently show up in white supremacist propaganda. In 2017, Vanguard America flyers posted in Texas, Indiana and elsewhere urged readers to “imagine a Muslim-free America,” as did Atomwaffen flyers reported in Pennsylvania. The following year, Identity Evropa members in Dearborn, Michigan, posted flyers reading, “Danger: Sharia City Ahead.” Some white supremacists have even posted flyers at mosques.

White supremacists have also taken part in various anti-Muslim protests. When anti-Muslim extremists organized the June 2017 “March Against Sharia” events in cities around the United States, white supremacists rushed to attend, taking part in at least eight such events. Among the white supremacist groups that participated were the Rise Above Movement, Identity Evropa, League of the South, Vanguard America, and Generation Europa.

Other Enemies

The list of the peoples white supremacists hate is virtually never-ending. LGBTQ people, to them, are “Sodomites” and “degenerates” who seek to weaken the white race. “The Sodomites want to take over our community,” proclaimed Arkansas Klan leader Thom Robb on Facebook in June 2018 while organizing a “Rally for Morality.”

As part of the far right, white supremacists also have a significant degree of political sinistrophobia, or fear and loathing of the left, which they often equate or conflate with Jewish influence.

White supremacists will occasionally admit to grudging respect for Asian people—typically Chinese or Japanese. This stems from white supremacists’ reliance on studies of IQ tests to “prove” white superiority over other races, studies that tend to reveal even higher scores for people of Asian descent. White supremacists also often cite Japan as an example of an ethnostate. Indeed, white supremacists even invited representatives from the right-wing nationalist Japan First Party to a white supremacist conference in Tennessee in June 2018. Makoto Sakurai, the group’s leader, and one other representative showed up; Sakurai, according to the organizers, “gave a candid view of the harm that has routinely accompanied Korean and Chinese immigration in Japan.”

That said, white supremacists still tend to reject the idea of Asians living among whites. “They’re still nonwhite,” explained one Stormfronter in February 2018 in a discussion on whether Asian-Americans were allies or enemies, “and therefore they don’t belong in white countries.” Another poster agreed: “If they are Non White [sic] they are an enemy.”

White Supremacy and the Alt Right - A NEW RELATIONSHIP

It is undeniable that white supremacy in the United States today is profoundly affected and influenced by the alt right, which is currently its most energetic segment. The alt right seemed to emerge from nowhere to capture headlines and attention. Indeed, as late as early 2015, the alt right still seemed to be a relatively minor part of the white supremacist movement.

But it was that same year—the year that Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president—that the alt right really expanded and increased its activities, at least online. It was also in 2015 that the non-white supremacist world began to become aware of the alt right, or at least its most public manifestations, such as the coining of the word “cuckservative,” a portmanteau of “cuckold” and “conservative.” The alt right uses it to refer to conservatives they deem weak, especially for not daring to address “the Jewish question.”

Even as people became aware of the term “alt right,” however, a great deal of confusion surrounded—and indeed still surrounds—its usage. A number of people have objected even to the use of the term “alt right” (a term derived from the longer phrase “alternative right”), because they believed it to be a euphemism for white supremacy in general. Others assumed that “alt right” was simply a pseudonym for neo-Nazi.

However, given that the alt right is not the whole white supremacist movement but merely part of it, the term remains useful, even necessary. The alt right is merely the newest segment of a white supremacist movement that already includes a number of other major segments—“traditional” white supremacists, neo-Nazis, racist skinheads, Christian Identity and Odinism, and white supremacist prison gangs.

These segments of the white supremacist movement have different histories, subcultures, demographics and emphases, but they generally share the core ideological conviction that motivates all segments of the white supremacist movement: that the white race is doomed to extinction unless white supremacists take action to prevent it. The alt right shares this concept of white supremacy, but it is different from other segments in many ways, from some of its other beliefs—pertaining to women, for example—to its unique subculture and its youthful demographics.

The rise of the alt right has impacted the white supremacist movement in a number of ways, from cornering media attention to bringing in a number of new recruits, who tend to be full of energy but ignorant of many of the difficult lessons learned by older white supremacists. The alt right has stolen potential recruits from some white supremacist groups and movements even as it provides opportunities to others.

Prior to the advent of the alt right, the white supremacist movement had been relatively static in its make-up for decades. The last new segment to join the white supremacist movement were the racist skinheads, who appeared in the United States in the 1980s. For most of the past 30 years, the white supremacist movement has been relatively stable. Individual segments have increased or decreased in size or activity over the decades, but the basic composition of the movement did not change—until the rise of the alt right.

One of the best ways to understand the effects of the alt right on the white supremacist movement is to look at the impact made by the earlier rise of racist skinheads in the United States. Racist skinheads emerged via the marrying of elements of the traditional skinhead subculture with white supremacist ideology generally borrowed from neo-Nazis. Similarly, as will be seen, the alt right emerged through the combining of white supremacist ideology with several different Internet subcultures. In both instances, some individuals were more interested in furthering ideological goals while others focused on socializing with likeminded people.

Racist skinheads were a youth movement, typically attracting people in their teens or early twenties; the alt right is also youth-oriented. Both racist skinheads and the alt right brought a rush of recruits to the white supremacist movement, newly radicalized and full of energy. However, in both instances, their quick rise upset the equilibrium within the larger movement, which was not always quick to accept them. Racist skinheads, because of their subculture, looked different, dressed and spoke differently and even had their own music. Thanks to its online origins, the alt right did not initially look or dress differently, though as it emerged into the physical world, many alt right adherents did distinguish themselves by measures such as adopting “fashy,” i.e., fascist, hairstyles and certain types of clothing for public events. But the alt right

did have its own slang, its own conventions and rituals, and its own memes, which were not always easy for older white supremacists to grasp, much less embrace. Some white supremacists of the 1980s, such as Tom Metzger, rushed to embrace racist skinheads, viewing them as potential new followers whom more established white supremacists could “educate” and guide. Others kept their distance. Similarly, some of today’s older white supremacists, such as David Duke and Jared Taylor, have been quick to embrace the alt right, while others have been more stand-offish. Racist skinheads were in some ways actually a threat to other segments of the white supremacist movement, such as neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan groups, because they could poach young recruits that all white supremacists are desperate for. Today, the alt right represents a similar threat to some other segments of the white supremacist movement, with racist skinheads themselves perhaps the most vulnerable.

Eventually, by the 1990s, racist skinheads had largely “settled in” with the white supremacist movement, establishing a new equilibrium. The same is likely to happen with the alt right, if it lasts long enough. But for now, the alt right is still a destabilizing, even occasionally disruptive force within the white supremacist movement itself.

The Ideology of the Alt Right

The alt right is a strange stew, a conglomerate of elements from different online subcultures loosely held together by white supremacist ideology. Still new, the alt right wrestles with articulating a clear self-identity or even reaching rough consensus among its constituent parts, a struggle illustrated by the numerous splits and disputes within the movement in its short history.

A number of different beliefs came together in the 2010s to form the ideological basis of the alt right.

Paleoconservatism

The alt right’s ideological sources are as mixed as its subcultural influences. One of the most straightforward influences is paleoconservatism, reflected most clearly in Richard Spencer, his National Policy Institute, and his followers. Paleoconservatism is an obscure segment of

the American right that seeks not only limited government and traditional values but also a return to older, less enlightened attitudes on subjects such as race, religion, ethnicity and gender.

Though some beliefs common among paleoconservatives (also known as “paleos”) can be found as far back as the isolationists and “America Firsters” of the 1930s, paleoconservatism itself is newer, arising in the 1980s in large part as a reaction against neoconservatism, which paleos vigorously oppose. Paleoconservatism uneasily straddles the dividing line between mainstream conservatism and the far right; adherents who are too explicit about their beliefs on issues such as race and anti-Semitism sometimes find themselves “exiled” from

the mainstream right.

It is no coincidence that some of paleoconservatism’s most prominent voices, including figures like Joseph Sobran and Samuel Francis, were fired from mainstream conservative publications such as the Washington Times and the National Review for the bigoted nature of their content. Some paleos, most notably Patrick Buchanan, have managed to keep a foothold in the mainstream despite holding controversial views on race, culture or religion. Others, including Jared Taylor and Peter Brimelow, have more or less willingly self-exiled, finding receptive audiences for their views within the radical right.

Among paleoconservatives, opposition to immigration, multiculturalism, non-Christian religions and even the concept of equality is common, as is support for nationalism. Ironically, Paul Gottfried, one of paleoconservativism’s founders is himself Jewish. In spite of this, he has characterized neoconservatives as “ill-mannered, touchy Jews and their groveling or adulatory Christian assistants.”

The early 2000s, the era of the Bush administration and wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, represented the high-water mark for neoconservatism; paleos had little hope their views would find much of an audience. However, as public opinion soured on the wars and on the Bush administration and its neoconservative allies, paleos like Paul Gottfried and a new generation of right-wing activists—Richard Spencer is the most well-known example—sensed the opening of a window of opportunity and pounced. The term “alternative right” itself was coined in 2008 by Richard Spencer (Gottfried has also claimed credit); by 2010, Spencer had created Alternative Right Magazine, an online publication with himself as “executive editor” and Brimelow and Gottfried as “senior contributing editors.” The site described itself as a magazine of “radical traditionalism” attempting to forge a “new intellectual right-wing” outside establishment conservatism.

Though presenting itself as a form of renegade conservatism (see below), what Spencer and others in the alt right really hoped to accomplish was reinjection of their racist views into mainstream conservatism, to carve out a place for themselves within the conservative movement and to make their racism and anti-Semitism more acceptable. Alt right adherents influenced by paleoconservativism tend to be particularly interested in mainstream politics, more so than other alt righters. The birth of the alternative right coincided with a resurgence of right-wing extremism following the election of Barack Obama as president, but the alt right was mostly unable to capitalize on this resurgence—its time would come later.

Neo-Nazism and Fascism

Another ideological influence on the alt right is neo-Nazism. Neo-Nazis are white supremacist groups that revere Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany and adopt many of the trappings, symbology and mythology of the Third Reich. Neo-Nazis also adopt its extreme anti-Semitism, though many Hitlerian notions were dropped along the way, such as seeing Slavs as subhumans (modern white supremacists simply see them as “white”).

The best-known alt right figure associated with neo-Nazism has been Andrew Anglin, the Ohio-based founder of the Daily Stormer, which grew to be one of the most popular white supremacist websites. The Daily Stormer was an attempt to repackage Anglin’s earlier website, Total Fascism, into a punchier, more enticing format.

As its name suggests, Anglin’s inspiration was Der Stürmer, the crudely racist and anti-Semitic newspaper published by Nazi Julius Streicher from 1923-1945. Anglin used Nazi-inspired graphics for his website, as well as sections labeled “The Jewish Problem” and “Race War.” Posts on the site were very much in the spirit of Streicher, such as “The Disturbing Rites of the Jews,” “Robin Williams Suicide: Jew Gold Doesn’t Bring Happiness,” and “Thousands of Ratlike Jews Demonstrate in Israel.” With similar language, Anglin also attacked blacks, Muslims, women, LGBTQ people and other minorities.

Anglin, fluent in 4chan subculture (see next section), also helped merge that subculture with hardcore white supremacy, frequently using its memes and language. Eventually, Anglin even created a guide to the alt right for “normies” (i.e., non-adherents), that explained many of its memes and terms.

By 2017, Anglin toned down some of the Nazi-influenced graphics on the Daily Stormer, replacing them with images of the American flag and George Washington, though the site’s language did not change and Anglin continues to make Nazi references.

Nazi and fascist influences can be seen elsewhere in the alt right as well, in its language, memes, and even the screen names of its adherents. People who equate the alt right with neo-Nazism are incorrect, but neo-Nazi influences are certainly evident in the alt right.

Identitarianism

Another ideological influence on the alt right is identitarianism, which some have described as the European equivalent of the alt right, though that is only true in a loose sense. Identitarianism is a right-wing European movement that originated in the early 2000s in France and spread to other European countries. Like the alt right, identitarians attracted many young people to their ranks. At their simplest, identitarians are nativist nationalists who oppose non-white (and especially Muslim) immigration into Europe, as well as the continued existence of Jews and Roma within Europe. Though there are different strains of identitarianism, most seek to change European countries into right-wing, nationalist ethnostates; most also share a Europeanist vision of a Europe cleansed of “alien influences.”

Identitarian ideas have made their way into the United States, where they are very compatible with views such as paleoconservatism. Richard Spencer, for example, has proclaimed himself an identitarian and his National Policy Institute sponsored a “Why I’m an Identitarian” essay contest. American identitarianism is somewhat different from its European counterpart because America is a melting pot of different cultures and ethnicities. Thus for American identitarians the idea of a white ethnostate has largely replaced the idea of national ethnostates, such as a purely Hungarian Hungary. Some Southern white supremacists have even combined identitarianism with “southern nationalism,” calling for a Southern white ethnostate—this concept is sometimes known as the “alt South.”

Identity Evropa is the largest identitarian alt right group, claiming its objective is to “create a better world for people of European descent, particularly in America.” Like Spencer, with whom it was initially aligned, Identity Evropa also takes an interest in conservative politics. In an article posted to its site after some of its members attended the 2018 Conservative Political Action Conference, Patrick Casey, the group’s leader, urged his followers to become active in politics by joining the College Republicans or running for office. “Trump has given us the opportunity,” Casey wrote, “to transform the GOP from a vehicle for Conservatism Inc. to one for Nationalism, and it’s up to us to seize the opportunity.”

Renegade Conservatives

An important influence on the alt right has come from other right-wing figures and publications that consider themselves renegade conservatives who are opposed to neoconservatives, “cuckservatives,” and establishment conservatives in general. By far the most influential entity of this sort has been Breitbart News, the right-wing website started by Andrew Breitbart in 2007 and continued by Steve Bannon after Breitbart’s death in 2012.

Bannon took Breitbart News down a darker road, emphasizing nationalism, anti-immigration, anti-Muslim and other themes that were popular among alt right adherents, many of whom became enthusiastic readers of and commenters on its content. One former Breitbart editor described the site’s comments section as a “cesspool for white supremacist mememakers [sic].” In 2016, Bannon himself even declared that Breitbart was “the platform of the alt-right.”

Though it seems that Bannon was referring to what would later become known as the alt lite rather than the explicit white supremacists such as Richard Spencer, Breitbart did hire figures such as Milo Yiannopoulos to write for the site. Yiannopoulos, though a gay man who has claimed not to be racist, is a consummate right-wing troll with connections to a variety of clearly racist alt right figures, from Andrew Auernheimer to Vox Day. An investigation by Buzzfeed revealed further that some members of Yiannopoulos’s own entourage of assistants and ghost writers were also racists or white supremacists, such as Tim “Baked Alaska” Gionet and Mike “Mike Ma” Mahoney. One former Yiannopoulos ghostwriter, Lane Maurice Davis, was later arrested in 2017 for the murder of his father, allegedly because his father had called him a Nazi and a racist during an argument.

Right-wing Conspiracy Theorists

Equally influential on the alt right are right-wing conspiracy theorists, who provide raw material for the alt right’s constant attempts to ignore or even erase the line between fact and fiction.

Of these, perhaps the most well-known is Alex Jones, the anti-government conspiracy theorist who emerged in Texas in the 1990s as a proponent of militia-style “New World Order” conspiracies. From his obscure beginnings, Jones built a right-wing counterculture media empire, providing himself with a prominent—and lucrative—pulpit from which to blast his outrageous accusations, which he complements with rants, tears and occasional shirtlessness. As his influence grew, even then-presidential candidate

Donald Trump appeared on his show in December 2015.

Despite not being a white supremacist himself (Jones emerged from the anti-government extremist wing of the far right), Jones has a fan base among alt right adherents, not least for his support of Trump and his promotion of conspiracy theories such as Pizzagate, a right-wing fiction that a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor was the source of a child trafficking ring linked to Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

Paul Joseph Watson, an Alex Jones acolyte from Great Britain, has become even more popular among the alt right. Considerably younger than Jones, Watson is closer in age to most alt right adherents and even more adept at using social media, with well over a million YouTube subscribers and some 876,000 Twitter followers. Over time, Watson’s output has evolved from New World Order-style conspiracy material to content more in-line with an alt right audience, including anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric as well as support for Trump.

Mike Cernovich, the California-based conspiracy theorist and Internet media personality, is just as influential and even closer to the alt right. Cernovich—another key propagator of Pizzagate and other, similar conspiracy theories—even identified as being part of the alt right at one time, once tweeting that he was drawn to the alt right “after realizing tolerance only went one way and diversity is a code for white genocide.” That last phrase is a popular white supremacist slogan but as the alt right became more associated in the public mind with white supremacy, Cernovich has tried to distance himself from it, aligning himself instead with the less overtly racist alt lite. Cernovich is also known for his misogyny and ties to the “manosphere” (see next section).

Jones, Watson, Cernovich and lesser conspiracy theorists have all depended on and used the alt right as part of their bases of support, while at the same time providing alt right adherents with a steady stream of conspiracies and fabrications to imbibe and spread.

The Subculture of the Alt Right

One of the distinctive characteristics of the alt right is that its adherents share not only an ideology but also a subculture. Subcultures—such as the punk subculture or the goth subculture—are bound together by shared values, language and rituals, clothing, music, practices, or attitudes. The skinhead subculture, for example, developed its own slang, its own preferred styles of dress (such as “boots and braces,” i.e., Doc Marten work boots and suspenders), its own music (Oi!), and more.

The alt right has its own subculture as well, much of it adopted from other movements and subcultures that have evolved on the internet and whose practitioners have considerable crossover with the alt right. Of these, two in particular have had an outsized influence on the alt right: the “manosphere” and the imageboard subculture of websites like 4chan, 8chan and sections of Reddit.

The “Manosphere”

For decades there have been various groups or movements that have advocated “men’s rights” of some form or another. Some of these past groups have raised issues about subjects such as courts and custody.

Others have been little more than platforms for anti-feminism and toxic masculinity and have occasionally had ties to far right movements.

In the 2000s, however, a different sort of male-oriented phenomenon emerged, not really an organized movement so much as a community filled with people who resented or even hated women. They tended to believe that males were generally being emasculated by women and stripped of power and influence (a concept sometimes known as gynocentrism). They also were hostile to women on a personal level, with some believing that women were mere objects to be possessed and used for sexual gratification and others developing resentment towards women for their own inability to attract them or to form meaningful relationships with them. Though this community—which exists primarily online—takes several different forms, collectively it is often referred to as the “manosphere.”

One segment of the subculture consists of the so-called “pickup artists” or PUA, sometimes known as the pick-up community or the seduction community. Pickup artists trade strategies for psychological or physical manipulation of women for purposes of having sex. Perhaps the most well-known PUA is Daryush Valizadeh, aka Roosh V, who operates the Return of Kings website and has had ties to the alt right himself.

Another segment centers on “incels,” a portmanteau for “involuntary celibates.” This segment consists of men who, for reasons related to their physique, personality, or other attributes, find themselves rejected by women and who outwardly project their frustration and unhappiness as outright hostility or hatred towards women. They may also be resentful towards men who are more successful in forming romantic or sexual relationships with women. Some even promote rejecting society as a whole and living independently or “off the grid.”

Others in the community describe themselves as MGTOW or “men going their own way,” who urge males to forsake relationships with women and who claim to practice such a self-enforced celibacy themselves.

The manosphere has contributed a seething misogyny and resentment of women to the alt right’s other hatreds, making the alt right by far the most misogynistic segment of the white supremacist movement, as well as the segment with the fewest number of female adherents.

This may eventually contribute to future violence, as two deadly shooting sprees have already emerged from the manosphere. In 2014, a young manosphere misogynist, Elliot Rodger, killed six people and wounded 14 others in Isla Vista, California. More recently, in April 2018, a suspected Canadian incel, Alek Minassian, conducted a vehicular attack with a rented van in Toronto that killed 10 and injured 16 more.

Another source of the alt right’s misogyny has been the computer/video gaming community. While many women play such games—studies typically suggest women comprise somewhere between 35-50% of the gaming audience—men and women often tend to play different games, with certain game genres--first-person-shooters, for example—attracting a largely male base. Some of these male gamers have developed hostile attitudes towards women gamers, designers, and reviewers, which has often resulted in harassment campaigns against such women. This harassment is often collectively described as “Gamergate,” though the term also refers to one specific campaign to harass a particular female game developer.

Gamergate also showed alt right adherents the effectiveness of online harassment campaigns against perceived enemies.

The Chan Subculture

Perhaps the most important contributor to the subculture of the alt right are the so-called “imageboards,” a type of online discussion forum originally created to share images. Of these, the most important is 4chan, a 15-year-old imageboard whose influence extends far beyond the alt right, as a key source of internet memes from lolcats to rickrolling. Its /pol subforum, though, is a much darker place, the Mos Eisley of the internet, an anarchic collection of posts that range from relatively innocuous to highly offensive.

Over time, 4chan has become home to many racists and open white supremacists. Some of its imitators, such as 8chan, lean even more towards racism and white supremacy. Parts of Reddit, a popular website that contains a massive collection of subject-oriented discussion threads, also share the chan subculture, as do parts of Tumblr.

Imageboards such as 4chan are totally anonymous, without user names, allowing participants to say or post whatever they want, no matter how offensive, without fear of being exposed. Many take full advantage to engage in some of the most crude and blatant offensive language online, taking aim at many targets, not sparing even themselves. The chan subculture has a strong tendency to portray all such content as a joke, even when not intended to be, resulting in a strong “jkbnr” (“just kidding but not really”) atmosphere.

Over time, 4chan has evolved a unique argot, an elaborate slang vocabulary that makes parsing many 4chan posts difficult for the beginner (or “newfags,” as people new to 4chan are referred, as opposed to the “oldfags,” who are veterans). Terms and phrases can evolve from elaborate in-jokes, from other cultures (particularly Japan, as imageboards first originated in Japan), and from incorporating insults or epithets used by others. Much of this vocabulary has made its way into the alt right subculture. One example is the word “shitlord,” originally used as an insult against people making negative comments about LGBTQ people, minorities, obese people, and others, but adopted as a badge of honor by those opposed to so-called SJWs (“social justice warriors”).

Chan subculture also prizes hoaxing and trolling, with users taking pleasure in provoking strong reactions and often working together to propagate hoaxes and trolling attempts. In the past several years, for example, 4channers have engaged in a number of campaigns intended to convince journalists, “social justice warriors,” and liberals in general that any number of mundane signs or symbols are actually white supremacist symbols—from drinking milk to the rainbow flag to a polar bear emoji. Often they are successful; their campaigns spread on social media by credulous people.

The alt right has absorbed this aspect of chan subculture, just as it has an even darker aspect: online harassment campaigns against people who have angered them. Chans have engaged in such campaigns for years, even against targets as innocent as 11-year-old girls. The alt right has used similar tactics against perceived enemies, most notably in late 2016 when alt right rabble rouser Andrew Anglin initiated a targeted harassment campaign (he called it a “troll storm”) against Tanya Gersh, a Jewish woman and real estate agent from Whitefish, Montana, whom he accused of harassing the mother of another prominent alt right activist, Richard Spencer. Gersh received hundreds of hateful and even threatening e-mails and other communications, and is currently suing Anglin over the harassment campaign.

The Effects of the Alt Right Subculture

Having its own subculture allows the alt right to better define itself, to create in-groups and out-groups, and to create a sense of shared experience and solidarity. It adds a further dimension beyond the mere ideological, something that the alt right shares with the two other segments of the white supremacist movement that also have their own subcultures: racist skinheads and white supremacist prison gangs.

By the same token, though, that subculture can act as a barrier to interacting or working with other segments of the white supremacist movement; alt right activists immersed in the subculture can seem strange to other white supremacists, just as their racist skinhead predecessors seemed strange to white supremacists in a previous era.

Moreover, the presence of a strong subculture can also conceivably act as a hindrance to alt right activism, as least for some. Historically, many racist skinheads have been more interested in interacting socially with others who share their subculture—hanging out with other racist skinheads, listening to music, drinking—than they have been interested in engaging in actual white supremacist activism. For those skinheads, the shared subculture is actually more important than the ideology.

The alt right is susceptible to the same phenomenon, even though much of its subculture is online. It is likely that a number of alt right adherents are or will be more predisposed to interacting with other alt right adherents online than engaging in white supremacist activism in the real world. To the extent that this may occur, it can cause the alt right to have less of a real world impact than its sheer numbers might suggest, simply because not all alt righters are necessarily interested in ideological, on-the-ground activism.

Alt Right Tactics and the 2016 Presidential Election

In the alt right’s early years, alt right activism was limited, primarily because the alt right was small and strongly centered around paleoconservatism, consisting of little more than the occasional conference of an organization like Richard Spencer’s National Policy Institute. Its 2011 conference, “Towards a New Nationalism: Immigration and the Future of Western Nations,” featured speakers such as Spencer, Jared Taylor, Sam Dickson, Peter Brimelow, and others. The conference overview promoting the event left no doubt that its “new nationalism” was racial (i.e., white) nationalism.

What really spurred the alt right to action was Donald Trump’s announcement in the summer of 2015 that he would be a candidate for the Republican nomination for president of the United States. Trump was very popular with the alt right, as he was with most segments of the extreme right in the United States. Alt right adherents liked the fact that he was an outsider, an anti-establishment candidate, and believed that his views on subjects like immigration and Islam were close to their own.

The alt right did not imagine that Trump was one of them, and they certainly did not like it when he indicated support for Israel, much less the fact that he had a Jewish son-in-law and a daughter who had converted to Judaism. But they nevertheless perceived Trump as someone significantly aligned with their views, perhaps more so than any other major Republican candidate since Pat Buchanan. Many alt right adherents believed that Trump was good for them, whether or not he was one of them.

The alt right’s enthusiasm for Trump initiated what many in the alt right referred to as the “Meme Wars,” when alt right adherents and their various allies came out—online, at least—in support of Trump. The Meme Wars can be explained as an onslaught of postings, graphics, videos, conspiracy theories and other types of content that supported Donald Trump and targeted Hillary Clinton and anyone perceived as supporting her.

During the primary season and then the general election, the alt right Meme Wars exploded into overdrive, spurred on by controversies over Pepe, the frog cartoon that became a popular 4chan meme and was later adopted by the alt right, and by Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” comment, in which the Democratic candidate suggested that half of Trump’s supporters could be put into a “basket of deplorables,” because they were racist, homophobic, xenophobic, or Islamophobic. Trump-related Pepe and Wojak (another cartoon 4chan image) memes proliferated; after the election, one opportunist even (unsuccessfully) attempted to crowdfund a coffee table book dubbed The Donald: A Collection from the Meme Wars that would feature the “best” such pro-Trump memes.

This Trump-spurred activity included a great deal of harassment, most notably of journalists, thanks to the fact that journalists and alt right adherents both tended to be avid Twitter users. In particular, Jewish journalists as well as those perceived to be Jewish were targeted with online harassment, while many other journalists were accused of being Jewish as part of the harassment. The Anti-Defamation League documented instances of at least 800 journalists receiving anti-Semitic tweets, with prominent Jewish journalists receiving the bulk of the messages. This activity began in 2015 but greatly increased in 2016 as the presidential campaign ramped up.

During this campaign of harassment, use of the so-called “echo” became particularly popular with the alt right (and, later, other white supremacists as well). The echo consists of three sets of parentheses placed around the name of a person (such as a reporter) or an entity (such as a newspaper) that are intended to be a typographical coded signal that the person or thing within the parentheses is Jewish. Thus a reference to the (((New York Times))) is in effect a reference to the “Jewish” New York Times.

The Meme Wars and the harassment campaign against journalists ensured that journalists became very aware of the existence of the alt right. Many began writing about it, usually responsibly but sometimes sensationally. The coverage in general resulted in a deluge of publicity for the alt right—indeed, this was perhaps the most concentrated journalistic attention to a subject related to right-wing extremism since coverage of the Oklahoma City bombing and the militia movement in 1995. The publicity about the alt right actually helped its numbers grow, as more young white males became aware of the existence of the alt right and some found it attractive.

Media coverage thus spurred more alt right activities which in turn spurred more media coverage, creating a cycle in which the interplay of the election, the media and the alt right itself allowed the movement to grow considerably in 2016. By the eve of the election, many alt right activists had felt that, regardless of whether or not Trump won the election, they themselves had notched a victory. “I think if Trump wins,” Richard Spencer told a journalist for Mother Jones, “we could really legitimately say that he was associated directly with us, with the ‘R’-word [racist], all sorts of things. People will have to recognize us.”

What Spencer really hoped the election would do was shift the so-called “Overton window,” a term used to describe the range of acceptable discourse in society from “unthinkable” to “popular.” Spencer and many other alt right adherents who constantly refer to the Overton window hoped to move white supremacist beliefs from the “unthinkable” range closer to the “popular” segment of the Overton window—in other words, making such beliefs more acceptable. The alt right considered the election to be a step in that direction.

The Alt Right Now - Moving into the Real World

Alt right activists quickly moved to capitalize on the momentum and publicity bestowed by the long presidential campaign season. Richard Spencer launched a new alt right website just days before Trump’s inauguration in January 2017; one of its editors proclaimed that with the inauguration of Trump, “we are going to need to create a bigger platform to advance our agenda in the years ahead.” Spencer and many other alt right advocates also showed up at the inauguration to support Trump (where Spencer himself became the subject of a viral video when he was punched by a protester).

Alt Right Groups and Events

One key aspect of the evolution of the alt right was the creation of real-world groups and organizations. Prior to the election, there were very few alt right groups, as most adherents operated online. Richard Spencer’s National Policy Institute was not really an “institute” so much as a vehicle for Spencer’s speaking engagements and conferences.

The first notable real-world alt right group, Identity Evropa, emerged in the months prior to the 2016 presidential election. Originally led by Nathan Damigo (later by Patrick Casey), the alt right group has primarily targeted college campuses, holding events and putting up flyers. After the election, it quickly expanded and became one of the most visible alt right groups in the country. Identity Evropa doesn’t acknowledge that it is a white supremacist group—claiming instead to be patriotic and “identitarian”—but the organization is steeped in white supremacist ideology.

Another prominent alt right group is Patriot Front, based in Texas and led by Thomas Ryan Rosseau. It formed in August 2017 as a breakaway faction of neo-Nazi group Vanguard America but adopted an alt right sensibility. Like Identity Evropa, it attempts to position itself as a “patriotic” American group promoting “American Nationalism;” also like Identity Evropa, its membership is primarily young men.

Other groups followed, many of them regional or local in nature. The Rise Above Movement emerged in California, billing itself as a mixed martial arts club of the alt right. Patriots of Appalachia emerged in West Virginia, Identity Acadia in Louisiana, True Cascadia in Oregon, the Beach Goys in California, and so on. Followers of Andrew Anglin began to form local “Daily Stormer Book Clubs,” some of which started engaging in group activities like flyering. Collectively, these alt right groups gave the movement a real-world presence it had been lacking before the election. It also meant that communities, colleges and neighborhoods across the United States were now encountering alt right activities.

In addition to group formation, the alt right’s expansion into real-world activities following the presidential election included taking part in white supremacist events, such as conferences, rallies, protests, counter-protests and other gatherings. Familiar activities for the rest of the white supremacist movement, these events were new experiences for many newly-minted alt right activists.

From the start of 2017 through the first half of 2018, the Anti-Defamation League identified 120 events, public and private, organized or attended by white supremacists around the country. Alt right activists organized or were among the attendees at slightly over half of these events (64 of 120, although it is likely some of the other events included alt right attendees unidentified by ADL). Of these white supremacist events, alt right activists actually organized or helped organize at least 40 (it is not always possible to identify the organizers of every event). Identity Evropa and Patriot Front, the two most energetic alt right groups generally, were also the most frequent organizers of events, especially in 2018.

Selected Significant Alt Right Events in 2017 And 2018

MAR | 2018

Nashville, Tennessee

About 50 Identity Evropa members participated in a flash demonstration at Centennial Park.

MAR | 2018

Burns, Tennessee

Identity Evropa held its first “national conference.”

MAR | 2018

East Lansing, Michigan

Richard Spencer held a speaking event at Michigan State University, with about 20 attendees. An additional 40-50 were unable to get past antifa counter-protesters.

OCT | 2017

Charlottesville, Virginia

About 40-50 white supremacists, organized by Richard Spencer, The Right Stuff and Identity Evropa, took part in a flash demonstration.

SEP | 2017

Houston, Texas

Roughly 30 members of Patriot Front, Daily Stormer Book Club and other groups protested an anarchist book fair in Houston.

AUG | 2017

Charlottesville, Virginia

About 500-600 white supremacists, from the alt right and other segments of the white supremacist movement, held a massive two-day event dubbed “Unite the Right.”

MAY | 2017

Charlottesville, Virginia

Alt right activists from Identity Evropa, The Right Stuff, and other groups joined other white supremacists for a flash demonstration in Charlottesville to protest the removal of Confederate monuments.

This is a significant number of alt right events, though it must be noted that many of them were very small, such as a group of around 10 Identity Evropa members gathering at the Mexican Consulate in San Diego in May 2018 to hold a small flash demonstration, or a handful of Patriot Front members holding a demonstration at the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C., in June.

Most other alt right events from 2017-2018 were smaller, often involving between five and 20 participants. A number of alt right events from the past two years were organized as flash demonstrations. A flash demonstration is a surprise event organized with some degree of secrecy and little or no prior announcement or publicity. Message and chat apps help organizers spread the word without alerting opponents or authorities.

Flash demonstrations have disadvantages for the white supremacists, in that they tend to be smaller—because organizers can’t as easily get the word out to allies and other potential participants as they could if the event were being publicly organized and promoted. They also run the risk of getting less attention if the media does not know about the event beforehand. However, the surprise value, amplified by post-event social media promotion, can sometimes attract useful attention for the white supremacists, as can events where select members of the media are alerted.

One of the main advantages of flash demonstrations is that antifa and other anti-racist activists are much less likely to learn about such an event and show up to protest. For decades, most white supremacist public events have tended to attract massive counter-protests and have been attended by far greater numbers of anti-racist activists than white supremacists. These protesters, some of whom seek to engage in violence against the white supremacists, often have the power to drown out whatever messages or impressions the white supremacists wish to convey, or even to substantially disrupt the event, as was the case with Richard Spencer’s Michigan State University speaking event in May 2018, where most of his supporters were unable even to get to the building where he was speaking in order to hear him. That event, in fact, caused Spencer to cancel his planned college speaking tour while putting the blame on antifa and other counter-protesters.

Indeed, the appeal of flash demonstrations has spread beyond the alt right to other segments of the white supremacist movement. Groups such as the Shield Wall Network, the League of the South, and Keystone State Skinheads/Keystone United also used this tactic in 2018.

Despite the recent growth of the alt right and its willingness to engage in real-world events, many recent white supremacist events have still had no noticeable alt right presence. Some of these were single-group events, where one would not expect such a presence if a non-alt right group had organized it, but there have been other events with multiple white supremacist groups participating—but no alt right adherents. It doesn’t appear that these white supremacists necessarily deliberately excluded alt right groups and activists—but they don’t seem to have reached out to invite them, either.

White supremacist events have occurred all around the country. States with larger populations, such as California and Texas, have hosted a significant number of such events, as have smaller states that are home to active groups, such as Arkansas, where a number of Shield Wall Network and Knights Party events took place. Two states have been particularly unfortunate in the number of white supremacist events held on their soil: Virginia and Tennessee. In Virginia, Charlottesville has been the nexus for events, with white supremacists returning to that city three times after their first event in May 2017.

However, it may be Tennessee which has, for its size, had the most problems with white supremacist events, organized by both alt right and non-alt right activists. From the beginning of 2017 through the first half of 2018, the Volunteer State has weathered no fewer than 14 white supremacist events, from Memphis to Knoxville and many places in-between.

A number of factors combined to make this so, including the fact that it is geographically accessible to the membership bases of several white supremacist groups such as the League of the South and Traditionalist Worker Party; several white supremacist groups have traditionally organized certain events each year in Tennessee. Some cities in the state have had Confederate monuments controversies that white supremacists seek to exploit; white supremacists have found several event locations in that state that they find relatively hassle-free and easy to use; and some white supremacists have speculated that Tennessee’s white population, especially in more rural areas, might be receptive to their messages.

The Alt Right Propaganda War: Podcasts

Despite the alt right’s move into the physical world, the internet remains its main propaganda vehicle. However, alt right internet propaganda involves more than just Twitter and websites. In 2018, podcasting plays a particularly outsized role in spreading alt right messages to the world.

White supremacists have used videos and audio, both in shorter forms as well as in longer “internet radio” shows or podcasts, for as long as those technologies have been available. Stormfront Radio, for example, dates back to the mid-2000s, and David Duke has long produced videos. However, in the past several years, alt right activists have created an entire universe of alt right-related podcasts (as have their alt lite counterparts), so many that, as one admirer accurately observed recently on the DebateAltRight Reddit forum, “There’s really too much for any 1 person to listen to.” Audio and video podcasting offers great advantages to the alt right. Millennial and Generation Z audiences, the prime recruiting pools for much of the alt right, are more likely to engage with these formats than others and more likely to watch or listen to an alt right show than read a long alt right ideological screed. Podcasts allow different alt right activists to reach out to people with a variety of styles and approaches to subject matter, building their own audiences—something that is key to the alt right, which doesn’t form actual groups as often as some other segments of the white supremacist movement. Moreover, audio podcasts allow alt right activists to maintain the anonymity that most of them desire. The length of alt right podcasts, which can range from around 45 minutes up to three hours, also makes it difficult for anti-racist groups and organizations to thoroughly monitor all such content.

Also important is the fact that the de-platforming strategies that have forced prominent white supremacists off many social media, crowdfunding and other platforms have not yet caught up to podcasting, and podcast hosting companies are not necessarily doing their own policing. This means alt right podcasts can be found, sometimes in abundance, on sites such as YouTube, Libsyn, PlayerFM, Spreaker, PodBean, and others. This makes it easier for alt right white supremacists to reach audiences with podcasting than through many other platforms.

Indeed, some white supremacists have even built what could be described as alt right media empires. The largest and most influential of these is the website The Right Stuff, run by Mike Peinovich, who uses the pseudonym “Mike Enoch.” Peinovich is one of the pioneers of the alt right, beginning his activism through blogging (The Right Stuff itself began as a blog).

In 2014, Peinovich began podcasting with what remains one of the longest-running and most popular alt right podcasts, The Daily Shoah (its name is anti-Semitic wordplay derived from the comedy television program The Daily Show and the Hebrew word “shoah,” meaning catastrophe, used as a synonym for the Holocaust). To date, Peinovich has produced more than 300 episodes of The Daily Shoah.

The Right Stuff also hosts many other podcasts. Fash the Nation, hosted by “Jazzhands McFeels” and “Marcus Halberstram,” is among its most popular podcasts, with over 125 episodes to date (“fash” is alt right slang term for “fascist”). “Southern Dingo” hosts the southern-centric The Southern AF podcast, with nearly 50 episodes. Strike and Mike is hosted by Peinovich and “Eric Striker,” the latter a popular alt right podcast figure. The Right Stuff airs KulturKampf, Fatherland, HateHouse, and more.

The content of these podcasts varies, but racist, anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant and misogynistic themes dominate. One recent episode of HateHouse, featuring host “Larry Ridgeway” and Robert “Azzmador” Ray, a writer for Andrew Anglin’s Daily Stormer, was titled “Thank God, they’re n*****s.” One fan of the show described the episode on the social media site Gab as Ridgeway and Ray “embellish[ing] on why they appreciate American n*****s. Lots of laughs in this one!”

The plethora of Right Stuff podcasts even include a number of “specialty” podcasts. One recent example has been CTRL Alt Right, which billed itself as “the #1 gaming podcast on the alt right.” One recent special episode, co-presented by the white supremacist gaming-oriented website Fash Arcade, was titled “Mr. Shoah with Bob & Shekel,” another anti-Semitic wordplay reference. With such specialized podcasts, the alt right can spread their message to specific audiences—in this case, gamers, whom alt right activists view as potential recruits.

Following in the footsteps of The Right Stuff is AltRight.com, the website run by Richard Spencer and Swedish alt right activist and publisher Daniel Friberg. It has attempted to duplicate The Right Stuff’s success by hosting and promoting a variety of podcasts of its own, including Alt Right Politics, Counter-Signal with Richard Spencer, Unconscious Cinema, Euro-Centric with Daniel Friberg, Interregnum, and The Transatlantic Pact.

These constitute just a drop in the disturbingly large bucket of alt right podcasts. Just a few others include shows such as Exodus Americanus, Myth of the Twentieth Century (named after a book written by a prominent Nazi), This Week in White Genocide, Rebel Yell, America First, and Nordic Frontier. Recognizing the popularity of podcasts, some alt right groups have created their own podcasts as well; one recent example is Identity Evropa’s Identitarian Action podcast, hosted by the group’s leader, Patrick Casey, and other group members.

Alt right podcasts are also a prominent way that alt right activists in the United States are able to share ideas with their alt right and identitarian counterparts in other countries. Canada has had several popular alt right podcasts, including The Public Space, hosted by French-Canadian Jean-Francois Gariépy, and This Hour Has 88 Minutes, hosted by Clayton Sandford (under the rubric “Axe in the Deep”) and Thomas White (as “League of the North”) until its recent demise. From Sweden comes Red Ice, with Red Ice TV and its sister show, Radio 3Fourteen (Red Ice also claims a “studio” in “North America”). Other alt right/identitarian English-language podcasts have come from other countries.

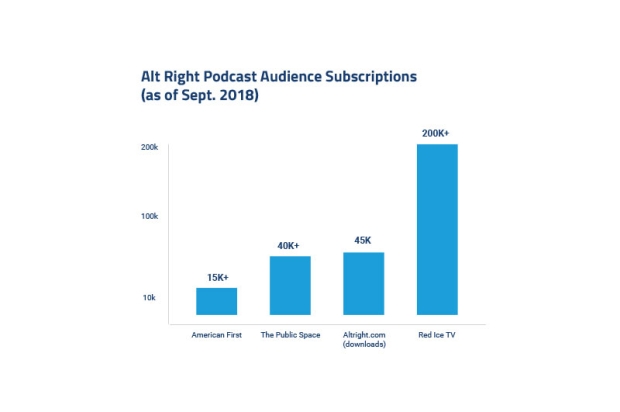

Alt right podcasts can’t get the huge audiences of mainstream podcasts, but can attain audiences that are quite large for white supremacists. Red Ice has more than 200,000 subscribers on YouTube, for example. The Public Space has over 40,000 subscribers; Nick Fuentes’ American First podcast has over 15,000 subscribers. On the podcast site Spreaker, Altright.com shows have had over 600,000 plays and nearly 45,000 downloads. One episode of Alt Right Politics alone, “Incels and the Next Sexual Revolution,” got nearly 18,000 plays. Altright.com has nearly 27,000 subscribers on YouTube. These numbers illustrate the extent to which the alt right relies on its podcasts to get its message out and the degree to which podcast- and video-hosting websites are key to the spread of such messages.

The Alt Right Propaganda War:

College Campuses

As the alt right has expanded into real-world activity, more communities have experienced alt right activism and publicity stunts, from flash demonstrations to white supremacist freeway overpass banners.

However, perhaps more than any other locations, college and university campuses have been the front lines for a concerted propaganda battle waged by alt right and allied white supremacist groups. More white supremacist activity has occurred at college campuses from 2016-2018 than at any other time in the history of the modern, post-Civil Rights era white supremacist movement.

At first blush, college campuses might seem a strange place to concentrate white supremacist activity, given the reputation of college campuses as liberal strongholds, and are not hospitable places for white supremacists. Indeed, demonstrations break out on many campuses when conservative writers or pundits are invited to speak, and some of those have become violent.

But white supremacist campus activities are not aimed at the majority of students. Rather, such efforts represent a form of counter-programming aimed at reaching the smaller number of students who disagree with the more liberal majority. Just as television networks do not attempt to compete for viewers with the Super Bowl but rather schedule shows that are more likely to appeal to people who have no interest in that event, white supremacists hope to reach a small and specific audience of conservative, disaffected students. Indeed, the more openly left-leaning a campus might be, the more there might be some conservative students feeling isolated and alienated—and theoretically, at least, possibly receptive to a message directed at them.

Moreover, most adherents of the alt right are young, many of college age. Even when they do not attend the colleges or universities they target—which seems to be the case much of the time, based on instances where perpetrators have been identified—universities are natural targets for them.

However, most of the time white supremacists have a broader goal than merely targeting the local students. Realizing that something like a white supremacist flyer has a high likelihood of stirring controversy on campus, they engage in such activities realizing that the incidents will be spread via traditional and social media to a much larger audience than just the students at that campus.

The most visible campus tactics involve white supremacist speakers invited to speak on campus or renting public meeting space on campus for an event. Because almost every such event will be protested by anti-racist protesters and the possibility of violence is very real, such events require planning by universities and law enforcement and can generate a large amount of publicity. Richard Spencer is the alt right adherent who has invested the most time and energy in this tactic, speaking recently at places such as Michigan State University, the University of Florida, and Auburn. However, other white supremacists, such as Matthew Heimbach and Ken Parker, have also taken advantage of this strategy. White supremacists have also occasionally shown up on college campuses for small flash demonstrations, as Identity Evropa did at Miami-Dade College in 2017.

White supremacist flyering, though, is by far the most common white supremacist campus tactic (the term used here for convenience is flyers, but this also refers to similar placement of handbills, posters, stickers and banners). Alt right adherents began such efforts with the 2016-2017 schoolyear and conducted a second campaign during the 2017-2018 school year.

Since September 2016, the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism has recorded 478 incidents of white supremacist propaganda on some 287 college and university campuses in almost every single state. The two most active alt right groups, Identity Evropa and Patriot Front, are responsible for the bulk of the incidents. Identity Evropa adherents engaged in 230 such incidents, while members of the Patriot Front contributed another 70. Daily Stormer Book Club associates targeted campuses with 16 flyering incidents. Neo-Nazi groups allied with the alt right such as the Traditionalist Worker Party, Vanguard America and the National Socialist Legion, have also contributed a few.

This propaganda has generally promoted the various groups themselves, certain popular white supremacist websites, and general white supremacist themes. They have also frequently targeted specific minority groups, including Jews, African-Americans, Muslims, immigrants and the LGBTQ community.

These campus-oriented efforts have garnered considerable publicity for groups like Identity Evropa and Patriot Front, which probably has added some people to their ranks, but overall it is hard to measure to what degree these efforts have brought any success to the groups engaging in them.

The Catch-88 Paradox - Optics and Backlashes

Shortly after the 2016 presidential election, an excited Richard Spencer told a National Public Radio correspondent that “This is the first time we’ve really entered the mainstream, and we’re not going away. I mean, this is just the beginning.”

Spencer’s dream of a grandly ascendant alt right, however, soon met with a rather harsher reality in the months following the election as Spencer and his fellow alt right adherents encountered a Catch-22 that has long bedeviled earlier white supremacists. The paradox—it can be called Catch-88 after the popular white supremacist numeric symbol standing for “Heil Hitler”—is simple: in order to accomplish their goals, white supremacists have to be active and attract publicity. However, because explicit white supremacy is quite unpopular in the United States, the more publicity white supremacists get, the more they make themselves vulnerable to exposure, negative coverage, and backlashes.

When the Catch-88 paradox manifests itself, it tends to have several effects on white supremacists. First, it spurs recriminations and squabbling among white supremacists as they experience its negative effects. Their first response is typically to blame Jews, but they often progress to blaming each other.

Catch-88 also frequently spurs arguments over white supremacist messaging and appearance—the so-called “optics” debate. Some white supremacists argue that the movement needs to avoid bad optics such as overt Nazi symbolism while stressing positive optics such as Americanism. Bad optics, they say, simply chase people away who might otherwise be receptive to the messaging. Other white supremacists disdain compromise and want to promote their views however they wish. White supremacists are typically reluctant to acknowledge the reality that, regardless of whether accompanied by Nazi flags or by American flags, hardcore white supremacist ideology is something most Americans reject.