Related Content

by: Rabbi David Sandmel

January 21, 2020

Update: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Oberammergau Passion Play has been postponed until 2022.

In 1634, the residents of the picturesque village of Oberammergau in the Bavarian Alps made a vow to perform a passion play every ten years as a sign of their gratitude to God for having been spared from a deadly plague. Today the Oberammergau Passion Play is performed every ten years, in years ending in zero, and will also be performed in 2034 – the 400th anniversary of its first performance.

Many in the Jewish community (and a good number of Christians as well) have critiqued the Oberammergau Passion Play for its portrayal of Jews and Judaism.

Earlier this month, Christian Stückl, director of the Oberammergau Passion Play, received the Abraham Geiger Prize from the Abraham Geiger College in Pottsdam, Germany. The College, founded in 1999, is the first rabbinical seminary to open in Germany since the end of World War II. The awarding of the prize highlights the efforts of Stückl and his colleagues to confront the anti-Semitic legacy of the play.

Over the past year, I have participated in a remarkable dialogue between Stückl and a small committee of religious scholars, both Jews and Christians, about the challenges of presenting a Passion Play in the 21st century.

The Passion Play is a central part of the town’s identity and pride; with rare exception, only those born in Oberammergau or those who have lived there for 20 years can participate in the play, either as actors or behind the scenes.

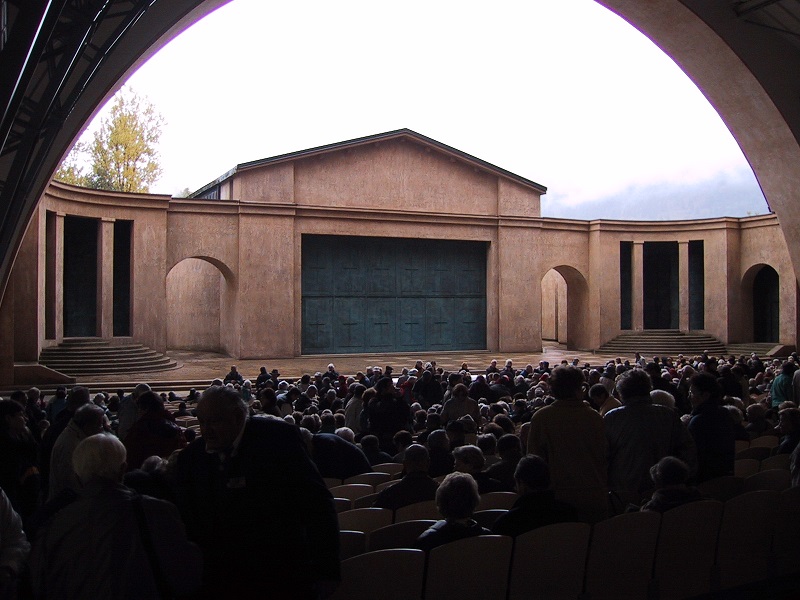

Beginning in the late 19th century, the play began to attract tourists (some might say “pilgrims”) and became an international phenomenon, drawing larger and larger crowds, eventually becoming the major economic engine for the town. Today it draws half a million people from around the world to see its 100 performances, between May and October in a special theater built for that purpose.

Passion plays (also known as Easter pageants) focus on the last week of the life of Jesus Christ: his entrance into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday; his railing against the hypocrisy of the Pharisees and the corruption of the priesthood; the High Priest’s decision to have him executed; his betrayal by the disciple Judas; his arrest and trials before the Jewish High Priest, Herod Antipas and Pontius Pilate; Pilate’s attempt to free the innocent Jesus but acquiescing to the Jewish “crowd” clamoring for his death, leading to the torture of Jesus and culminating in his excruciating death on the cross; and the resurrection.

These plays follow the narrative of the four Gospel accounts in the New Testament, homogenizing the sometime significant differences among them into a single narrative. The Gospels themselves are not categorically anti-Jewish (after all, most were written by Jews, for Jews, about Jewish subjects). However, as Christianity developed in the early centuries of the Common Era, attracting few Jewish but many Gentile adherents, it increasingly came to see Jesus and his teachings not as part of the complex Jewish world of the 1st century CE but as the polar opposite of a corrupt, carnal, even satanic Judaism, which demonstrated its perfidy by killing Jesus. As the church grew over the next several centuries, it increasingly came to interpret the Gospels through this lens: Jesus and the Christianity he inspired represented the good and the holy, while Judaism and those who stubbornly and blindly cling to it are evil. These ideas at are the core of Western anti-Semitism in all its guises.

Passion plays served the purpose, along with sermons and church art, to teach the story of the death and resurrection of Jesus to countless Christians, including the role of “the Jews.” In this way, the hatred of Jews became inextricably woven into the fabric of Christianity and Western Culture. As Eugene Fisher, who for many years served as associate director for Catholic-Jewish relations at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops was wont to say, Christian anti-Judaism was a necessary, but insufficient, cause for the Shoah, the genocidal massacre of six million Jews by the Nazis.

While the Nazis relied on pseudo-scientific “racial” theories, rather than religion, to portray the Jews as a threat to society, as vermin who needed to be exterminated, the image of the Jews as subhuman and a danger to humanity was able to flourish in the fertile soil prepared by centuries of the Christian teaching of contempt for Jews and Judaism. In light of this history, it is not surprising that Jews and their allies – including many Christians – who reject this, and all forms of bigotry, find passion plays so problematic.

The Oberammergau Passion Play had been filled with these negative portrayals of Jews and Judaism, some obvious, others more subtle. As was noted in a report from 1970, the play reflected “an ingrained negative attitude toward Judaism and Jewry… [I]t depicted the Jewish religious authorities as vicious, bloodthirsty and hypocritical, and Jewish law as punitive, harsh and vindictive.” The structure of the play pitted the Jewish people against Jesus and downplayed the power of Rome and role of Pontius Pilate.

Jews began to be aware of the play in the early 1900s and started writing about its problematic nature. Adolf Hitler attended the play in 1930 and again in 1934 (for the 300th anniversary), and described it as “essential to the Reich,” which no doubt significantly contributed to its growing notoriety and controversy. After the war, Jewish organizations started to critique the play publicly and demand changes in the text. The leadership of Oberammergau, a predominantly Catholic town, was initially hostile to this critique from Jewish outsiders, considering it an attack on their Christian faith and the community’s tradition and identity, and also a threat to its livelihood. Any communication, to the extent that it existed, was generally confrontational and largely unproductive.

Changes began to be introduced in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, which, in its historic document “Nostra Aetate” repudiated the ideas that “the Jews” both at the time of Jesus and today were responsible for his death, rejected anti-Semitism, and called for fraternal dialogue between Jews and Catholics. Catholic authorities from the archdiocese in Munich informed the Oberammergau community that the play needed to conform to current Catholic teaching. While some effort was made to address the problems, they were far from adequate, and Jewish organizations continued to condemn the play as perpetuating anti-Semitism.

For the 1990 production, Oberammergau native Christian Stückl, then in his 20s, became the director; this summer he is directing the play for the fourth time. Stückl’s appointment was controversial for some in Oberammergau, initially due to his age, but also to his willingness to take the criticism of anti-Semitism in the play seriously and address it. He has introduced significant changes into the play: For example, it now highlights Jesus’ Jewishness and he has removed the line from the gospel of Matthew in which the Jewish crowd states “His blood be on us and on our children,” the taproot of the deicide charge. However, the productions in 1990, 2000 and 2010 were deemed insufficient by some Jewish critics and the relationship between Oberammergau and representatives of Jewish organizations, such as ADL (the Anti-Defamation League) and the American Jewish Committee (AJC), was at times testy.

Nonetheless, Stückl and some of his associates began to develop real relationships with some of the Jewish representatives and, in advance of the upcoming 2020 performance, a new atmosphere of collaboration and trust emerged.

In March 2019, Stückl and Frederik Mayet, who handles public relations for the play (and is one of the actors portraying Jesus) came to the United States to meet with a small committee of scholars assembled by my friend and colleague Rabbi Noam Marans, Director of Interreligious and Intergroup Relations at the AJC. In addition to myself, Rabbi Marans recruited Rabbi Dr. David Fine of Temple Israel, Ridgewood, New Jersey and Abraham Geiger College, Berlin, Germany; Rev. Dr. Peter Pettit, St. Paul Lutheran Church, Davenport, Iowa and emeritus director of the Muhlenberg College Institute for Jewish-Christian Understanding; and Dr. Adele Reinhartz, a professor of religious studies at the University of Ottawa. We spent a full day together going through the 2010 script, highlighting problems in the text as well as in the staging and the costumes. Stückl and Mayet listened intently, asked insightful and probing questions and took prodigious notes. The committee subsequently produced a detailed report outlining our concerns and recommendations, which we sent to Stückl.

In October, our committee was invited to travel to Oberammergau as the community’s guests to continue the conversation. For two and half days, we discussed some of the most significant challenges such as how to handle the “Crucify him” line or how to make Caiaphas, the high priest, a three-dimensional figure caught between his loyalty to and concern for his people, his own ambitions, and the imperial power of Rome in the person of Pontius Pilate. We examined and offered our perspective on new costume and set designs. We noted significant changes even from the 2010 performance, evidence of just how seriously our recommendations were being taken. We met with the mayor of Oberammergau, who welcomed us and thanked us profusely for our efforts.

In addition to the specifics of the play itself, we had wide-ranging discussions of Jewish tradition and history and Jewish-Christian relations, as well as the history of Oberammergau and the play itself. The committee stressed the significance of the fact that the 2020 performances will take place at a time when anti-Semitism and other forms of hatred are on the rise in Europe and around the world. Germany, specifically, has seen dramatic increases in anti-Semitic incidents and violence in the last few years.

Stückl took all this in and we could see the wheels turning as he thought about how to take the recommendations of a group of academics and realize them in a dramatic performance, as well as how to preserve the traditions of his hometown, of Christian faith and scripture, and -- and this cannot be underestimated – how to factor in the preconceptions that a Christian audience brings to such a play that, for most of whom, is not merely a day at the theater, but a religious, spiritual experience. The story has to be recognizable and familiar. Our visit came several weeks before Stückl had to finalize all the aspects of the play (e.g., the script, the staging, etc.) for 2020; rehearsals began in December and the first performance is in May.

This means that we saw neither the final script nor a full-dress rehearsal and therefore cannot say how or to what extent this iteration of the Passion Play will reflect the kind of changes we think are necessary. I hope that I will have the opportunity to see the play once it opens to the public in May.

While substantial changes have already been made and I expect more as the production is finalized, I will not be surprised if there remains more to be done; this is an enormous challenge with competing factors and interests. Stückl, his team, and the leadership of Oberammergau are deeply and genuinely committed to this process, as they believe it is the right thing to do.

Passion plays continue to be performed all over the world; in some communities, it is a significant part of the history and culture – as it is in Oberammergau. Many of these plays still contain negative portrayals of Jews and Judaism. Oberammergau is an example of how relations and dialogue can achieve significant progress.