by: Oren Segal

July 07, 2016

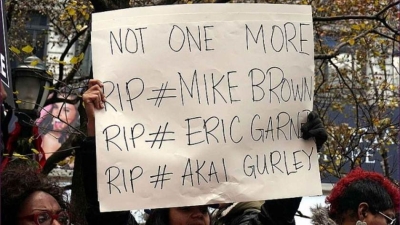

Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. Sandra Bland. Walter Scott. Freddie Gray. Tamir Rice. Michael Brown. Eric Garner. Tragically, the list goes on and on. According to The Guardian, at least 136 black people have been killed by police since the beginning of 2016, and 306 were killed in 2015.

For every person on that list, there is a family in mourning and friends who are in pain. Each time—as with the families and communities of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling today—our hearts go out to them. We hope that in sharing their grief, we will in some way lessen their pain just the tiniest bit.

But these deaths—and the deaths of hundreds of others like them—reverberate far past their families, their friends, and their local communities. Although the circumstances of these deaths are quite distinct from hate crimes, in some ways their impacts are analogous: they stoke fear in much broader communities. Each time a black man, woman, or child is killed by police, it strikes fear in the hearts of black and brown people across the nation. It erodes communities’ trust in the very people who took an oath to protect them. And it ignites anger at the injustice both of the deaths and, too often, the absence of accountability.

While black and brown communities surely feel the pain, the fear and the anger most acutely, it spreads much further. As Justice Sotomayor recently wrote in her impassioned dissent in Utah v. Streiff, “We must not pretend that the countless people who are routinely targeted by police are ‘isolated.’ They are the canaries in the coal mines whose deaths, civil and literal, warn us that no one can breathe in this atmosphere.”

It is long past time for change—not only for the memories of those who have died and for their families and communities who live on, but for all of us. When communities feel they cannot trust police, it creates a permanent underclass of people who cannot turn to law enforcement for help or protection. It means that entire communities may not call on the police not only when they are targets of crimes but also when they are witnesses who might have critical information to share. That makes all of us less safe, and it cannot continue.

Since 1999 the Anti-Defamation League, in partnership with the United States Holocaust Museum, has conducted trainings for law enforcement—from police chiefs and the head of federal agencies to recruits and new FBI agents—exploring what happens when police lose sight of the values they swore to uphold and their role as protectors of the people they serve. By contrasting the conduct of police in Nazi Germany, and the role that law enforcement is expected to play in our democracy, the program underscores the importance of safeguarding constitutional rights, building trust with the people and communities they serve, and the tragic consequences when there is a gap between how law enforcement behaves and the core values of the profession.

We need that kind of training more than ever, as well as increased anti-bias training for law enforcement officers. We need federal investigations by the Department of Justice, as the government has already promised in the Alton Sterling case, and often the appointment of independent prosecutors. We need to build police forces with racial and ethnic makeups that mirror the communities they serve. We need official statistics on police killings, tracking what happens and what has gone wrong each time. And we need to work tirelessly so that when we proclaim “Not one more,” it is not just a hope but a promise.