Related Content

When the school year begins, reviewing the class list is usually at the top of the to-do list for elementary classrooms. Teachers often take time to learn each child’s full name and spend time in the early days of school helping children get to know each other and their names.

Names are a core part of identity. Names often reflect a person’s cultural, religious, ethnic or racial identity and can connect to traditions of family, community, ancestry and history. A name may originate from a language other than the ones spoken at school or home. A name can have a special meaning or be a source of pride. Family names are sometimes handed down from one generation to the next. Last names can reveal and affirm family history, a merging of several names or a new and meaningful name.

Because names express our identity—who we are—it is essential that those caring for and teaching children get those names right.

Therefore, whether it’s at the beginning of the school year, welcoming new students to class mid-way through the year, or at year-end ceremonies and graduations, prioritize knowing and pronouncing students' names correctly.

For some students, the topic of names can be complicated, fraught or distressing—due to aspects of their identity. For example, if a student is an adoptee, they may have two names—their birth name and another name—or they may not know or never know their birth name. A non-binary or transgender student may have a different name than the one they were given at birth, but people in their lives who do not know this may inadvertently “deadname” them. In the past and present, students have twisted and changed names to tease, ridicule or bully others.

Some students may have a name that others find challenging to pronounce. What’s “challenging” for some to pronounce may be easy or come naturally to others, depending on the linguistic and cultural background of the person. With that in mind, others (including adults who voice carries great weight in the classroom) should never shorten students’ names, use a “nickname,” (not agreed to by the student) or continue to use the wrong pronunciation. To that student, the wrong name can feel like a sting or a microaggression every single time. To the rest of the class, mispronouncing or changing a student’s name, sends a message that the student’s name does not belong to them. When names are mispronounced, educators will sometimes explain that the name is “difficult to pronounce,” which is not a helpful or respectful response. It implies that there’s something wrong with that student’s name, rather than offering a teachable moment that one should practicing saying others’ names correctly.

When children enter our schools, they should not have to face an educator who mispronounces, disregards, or changes their name. When that happens, children can feel that their identity, family, culture or community is being disregarded, excluded or erased. When students’ names are used correctly and they are invited to explore and explain the origins and meaning of their names, they feel respected and included.

Here are ideas for getting to know students’ names:

-

When reviewing the class list before seeing students, practice saying each name aloud. If you get to a student’s name you're unsure about, ask other adults in the school who might know that student or search for pronunciation guides or recordings of that name. You can also ask all students (or their parents) to record and share the pronunciation of their names.

-

When getting to know students, let them know that you're doing your best to learn and remember everyone's name because it is important to get it right. Tell students that it's okay to correct you if you make a mistake, and when it happens, thank the student for correct you and try again. In order to not repeat the mistake, jot down notes or whatever might help you get the name and pronunciation right.

-

Avoid describing names as "difficult" or "unique," even if it's your own. If you want to share a personal story about your name, be sure to personalize it and describe your feelings rather than making universal declarations about what is normal or abnormal about names.

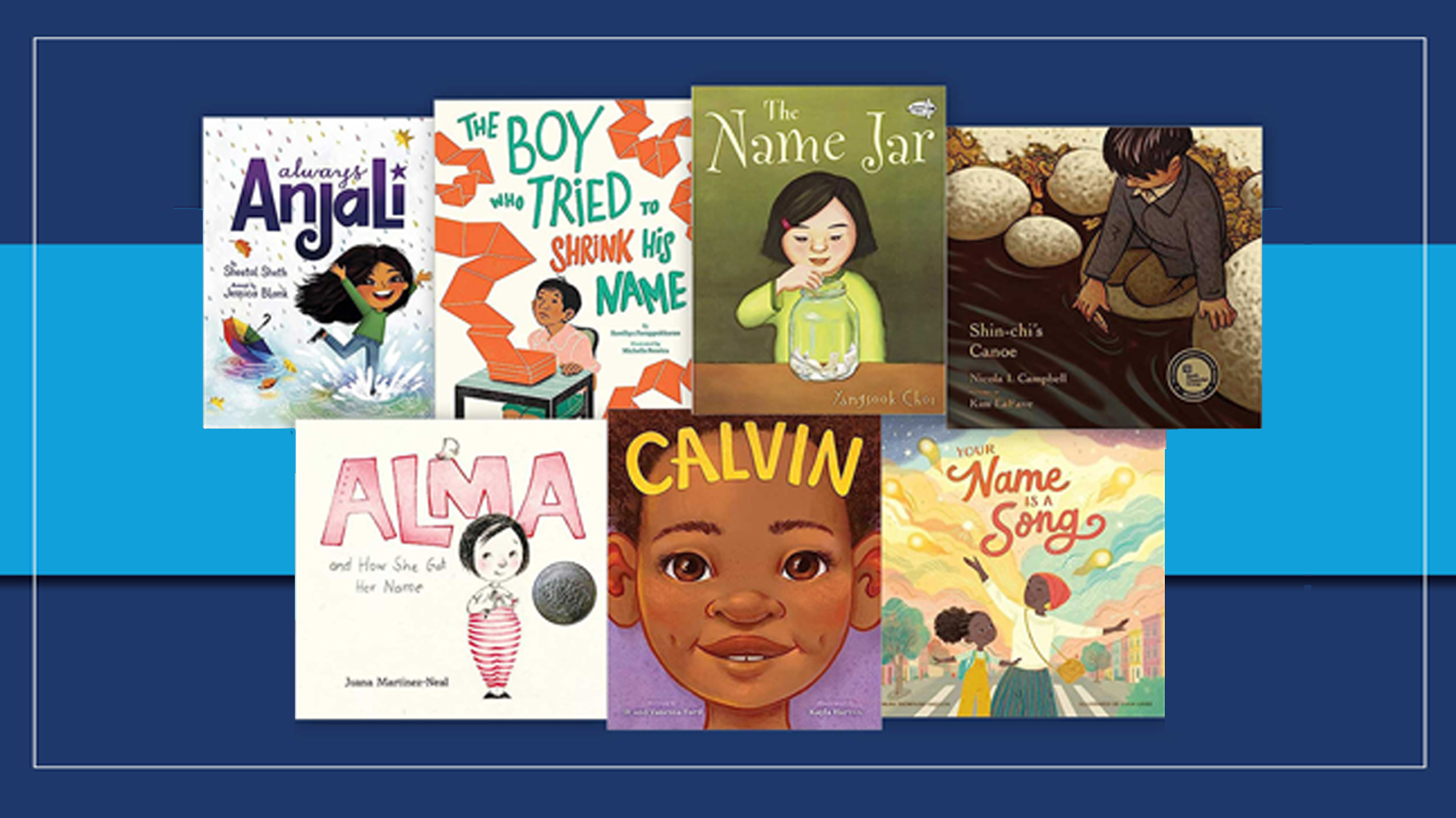

As you welcome students to school, use these books to open conversations about the importance of names, the seriousness of pronouncing names correctly and why we should not shorten names or give students nicknames. All are picture books but can be used for grades K-12 to discuss names. Most of these books include discussion guides for educators and parents/families.

Recommended Books

Alma and How She Got her Name If you ask her, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela has way too many names: six! How did she wind up with such a large name? Alma turns to Daddy for an answer and learns of Sofia, the grandmother who loved books and flowers; Esperanza, the great-grandmother who longed to travel; José, the grandfather who was an artist; and other namesakes, too. As she hears the story of her name, Alma starts to think it might be a perfect fit after all — and realizes that she will one day have her own story to tell.

Always Anjali Anjali and her friends are excited to get matching personalized license plates for their bikes. But Anjali can't find her name. To make matters worse, she gets bullied for her "different" name, and is so upset she demands to change it. When her parents refuse and she is forced to take matters into her own hands, she winds up learning to celebrate who she is and carry her name with pride and power.

Calvin Calvin has always been a boy, even if the world sees him as a girl. He knows who he is in his heart and in his mind and he finally decides to tell his family. "I'm a boy--a boy in my heart and in my brain," Calvin tells them. His family quickly supports him, taking Calvin shopping for the swim trunks he's always wanted and a new haircut that helps him look and feel like the boy he's always known himself to be. He's nervous about back to school but as his friends and teachers rally around him and he tells them his name, his "what-ifs" melt away.

Shin-Chi's Canoe When Shi-shi-etko and Shin-chi arrive at the Indian Residential School, Shi-shi-etko reminds her younger brother that they can only use their English names and that they are not allowed to speak to each other. For Shin-chi, life becomes an endless cycle of church mass, school and work, punctuated by skimpy meals. He finds solace at the river, clutching a tiny cedar canoe, a gift from his father, and dreaming of the day when the salmon return to the river—a sign that it’s almost time to return home.

The Boy Who Tried to Shrink His Name When Zimdalamashkermishkada starts at a new school, he knows he’ll have to introduce himself to lots of new people. He trips over his long name and decides to shrink it down to the shorter, simpler Zim. The nickname works fine for introductions, but deep down, it doesn’t feel right. It’s not until a new friend sees him for who he truly is that Zimdalamashkermishkada finds the confidence to step proudly into his long name.

The Name Jar Being the new kid in school is hard enough, but what about when nobody can pronounce your name? Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious that American kids will like her. Instead of introducing herself on the first day, she tells the class that she will choose a name by the following week. Her new classmates decide to help by filling a glass jar with names for her to pick from. But while Unhei practices other names, a classmate comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning.

Your Name is a Song Frustrated by a day full of teachers and classmates mispronouncing her beautiful name, a little girl tells her mother she never wants to come back to school. In response, the girl's mother teaches her about the musicality of African, Asian, Black, Latin American and Middle Eastern names on their lyrical walk home through the city. Empowered by this newfound understanding, the young girl is ready to return the next day to share her knowledge with her class.