A Message from Rabbi David Wolpe – ADL’s Inaugural Rabbinic Fellow

Hate is generic but hatreds are specific. Different kinds of prejudice play out in different ways, and the Jewish people have spent many centuries thinking about prejudice — and love — and how each flourishes in God’s world.

When the CEO of ADL, Jonathan Greenblatt, asked me to serve as the Inaugural Rabbinic Fellow of the organization, I realized it was an opportunity to enrich the Jewish teachings of this organization whose work to combat hatred flows from the sources of our tradition. Leviticus 19:17 alone may be taken as the motto of what we seek to accomplish:

Do not hate your brother in your heart.

We are all kin. While much of ADL’s work is monitoring those who would be destructive and taking action against them, ultimately we seek to change hearts. Through a weekly parasha (weekly Torah portion) commentary and other speaking and writing, I hope to bring this message from a century old organization and a millennial tradition to a divided and needy world.

Vayishlah – Why Didn’t Esau Kill Jacob?

12/13/24

When Jacob hears that Esau, the brother who has sworn to kill him, is coming with 400 men, “Jacob was greatly frightened (Gen. 32:8).” Yet after his encounter with the angel, from which he emerges limping, Jacob in fact does not send presents ahead but “he himself went on ahead.” He now has the courage to present himself to his brother without the propitiation of gifts or appeals to mercy by first parading his family.

Jacob’s confidence is justified. Instead of killing him, Esau falls on his neck and both weep. Why?

Rashbam (12th century) points out that Jacob is known for running away. When he deceived his father and took the birthright, he ran. When he left Laban’s house, he ran. Esau sees that Jacob has a limp. He can no longer run. The evader, the trickster, is straightforward and present. When Esau sees Jacob uneasy stride, he realizes this is a different person from the brother whom he swore to kill.

Benno Jacob was a German rabbi at the beginning of the 20th century. He, too, points to Jacob’s limp, but draws a different conclusion. Esau remembered a Jacob whom he took as arrogant and entitled. Now the arrogant brother is gone, and in his place is an older, limping man who had been wounded by life. Struck by the difference, according to Rabbi Jacob, Esau’s heart changed.

These are both cogent and interesting readings. Yet my favorite is one offered by my father, z”l.

Esau and Jacob were twins. They were not identical twins, but they had been born at the same time. They were the same age.

For most ancient people the world was without mirrors, and one rarely if ever saw oneself. Now for the first time in decades, Esau is confronted by his twin. Esau sees how old Jacob has grown and therefore recognizes how old he, too, has grown. Much of life has passed, wasted, in hate. Before Esau stands a mirror of the years and everything that has been lost.

Emmanuel Levinas, the French Jewish philosopher, wrote: “In front of the face, I always demand more of myself.” To truly see another person is to be better oneself.

At this hinge of history, Esau saw the face of Jacob, rose to the moment, and wept.

Previous Parashas

On this Thanksgiving, it is time to reflect anew on two kinds of gratitude.

Sitting at the Thanksgiving table, we feel grateful for the bounty we were privileged to enjoy. For the abundance of food we enjoy and the enormity of our nation’s gifts, we should offer heartfelt blessings. That alone is not enough; if we express thanks and do no more, is a feeling that leads nowhere. The second, deeper gratitude spurs us to give.

Motivational gratitude encourages us to help in a needy world. There are food banks and charities that count on donations and volunteers. Don’t end with appreciation; gratitude should be a green light for giving.

We are grateful for our family and friends. Yet our gratitude should be tinged with sadness for those who are alone, or for those who have lost people dear to them. The Jewish injunction at Passover – ”Let all who are hungry come and eat, let all who are in need celebrate Passover” – is the joining of appreciation to obligation. We who have so much should be grateful; we who have so much should also be mindful that others do not.

This is a tragic and unsettling time. If you are lucky enough to be surrounded by those whom you love, remember those who are not so fortunate.

This wonderful country is singularly blessed. Much of what we have is a product not of our goodness, but of God’s goodness and the efforts of others. We sit in homes we did not build, eating food we did not grow, speaking a language we did not create, surrounded by a world that was prepared for us before we were born. Like the old man in the Talmud planting a carob tree whose fruits he will not see, we should give to others as so many have given to us.

The lessons of Thanksgiving do not end with a full stomach and a football game. Gratitude for this wondrous but broken world should be a drive throughout the year to donate to worthy causes, to volunteer, to battle against hatred and prejudice and cruelty. Abundant in blessing and full of passion, we are called to give thanks, to bind wounds and to heal hearts.

In the Torah portion this week we have the first instance of someone weeping for a person whom they have lost. Abraham weeps at the death of his beloved wife, Sarah. He then purchases a burial cave, Me’orat Hamachpelah, in order to bury Sarah.

As commentators have noted throughout the ages, there is something poignant and paradoxical that the first bit of land the Jewish people acquire in Israel is a burial plot. This practice influenced later Jewish communities. Wherever Jews settled, one of the first acts of each community was to establish a Jewish cemetery. The Jewish people are drawing on an ancient precedent, but there is not only a practical aspect to Abraham’s act but a symbolic one.

The name Me’orat Hamachpelah, in the view of the rabbis, comes from the word kaphul, which means double. One implication is that couples will be buried there – Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah. But there is also a rabbinic opinion that says it is double because it represents this world and the next – that the entrance to the cave is also the portal to the garden of Eden. Death presages rebirth.

Abraham learned that you cannot love without loss. Equally, you cannot inherit a land without loss. Sacrifice is bound up with the legacy in the land of Israel. So too is love, which might be the answer to the second question that arises from the burial of Sarah.

If Abraham is promised the land by God, why must Abraham negotiate and purchase the land? One answer is that even God’s promise does not obviate human effort. We must work to realize whatever we achieve in this world.

It may also be, however, that Abraham feels that his love for Sarah means he cannot bury her in something he has not himself earned. She has accompanied him throughout his journey; love mandates that he make an effort to acquire the place where she will rest, and one day, he will rest beside her.

The themes of this parasha are the themes of Israel throughout the ages and today. Those who have fallen in defense of the land are what enable it to survive and flourish. From the days of Abraham, Israel is kaphul, double – a land built with loss and with love.

Reeling from the attacks in Amsterdam, our parasha has an important lesson to teach. This week we read about the city of Sodom. An entire city is consumed by wickedness, and despite Abraham’s attempt to save the city by bargaining with God, there is no righteousness there to save.

So when Abraham has to stay in Gerar, he does not trust the King, Abimelech. After all, he has just experienced the complete depravity of Sodom. Why should he believe that the King of another place will be better? Abraham claims that his wife Sarah is his sister, presuming he cannot protect her from the King’s advances. Yet God knows that Abimelech has a pure heart (Gen. 20:6) and preserves him from sin.

In other words, although we might be tempted to draw vast generalizations about hatred or wickedness, people differ. This brings me to a beautiful story.

My teacher Elieser Slomovic grew up in the border town of Solotwina in Eastern Europe. He and his family suffered terribly and growing up he was taught that the Christian world was inexorably hostile to Jews. When he came to the United States he found a teaching position in Los Angeles at what was then the University of Judaism. He taught Midrash to generations of students.

Shortly after arriving the President of the University asked him to represent the school at an interfaith conference. Professor Slomovic refused – he knew what Christians thought and believed and he wanted no part of it. The President insisted. Reluctantly, he attended the conference. At the opening dinner, the presiding Minister began the meal as follows: “I would like to start this meal as Jesus would have – Baruch atah h’ Elokeinu Melech Ha’olam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz” – the Hebrew blessing for bread. Many years later, as Professor Slomovic told me this story, he recounted how he got tears in his eyes, for he never knew that Christians could be so welcoming to the Jewish people. It was truly a different world from the one he left behind.

Perhaps Abraham learned this from Abimelech. When something awful occurs, as in Amsterdam, we need also to remember those who are allies and friends, people of good will, who stand with us to oppose such evil. The world is full of Abimelechs and if they all stand together, Sodom will be no more.

The silences of the Torah have for centuries moved people to interpretation. This week we have one of those great silences – God appears to Abraham. But what happened before? How did Abraham have any sense that there was a God in the world? Emerging from a background of idol worship, did he possess a special intuition?

The rabbis fill in this gap in several ways, telling stories of Abraham becoming disenchanted with his father’s idols, or realizing that neither the sun nor the moon was the eternal God. Even more poignant is the story that Abraham saw the world as a palace that was ‘doleket’. He asked – Does no one own this palace? Out of the sky came God and said – yes, I am the Lord of this palace. The key question is – what is ‘doleket?’

As pointed out by Abraham Joshua Heschel, doleket can mean either on fire or full of light. In other words, perhaps the first monotheist saw the world as a place of pain and destruction. But perhaps he saw the world as a pageant of wonder and miracle.

Like the gestalt image of the face and the goblet, we too can shift our sense of God’s world. Life is full of pain and loss and almost unfathomable tragedy. The past year has demonstrated anew how destructive human beings can be to one another.

Yet at the same time the world is full of discovery, of beauty and of love. There are moments when we understand that Abraham might have seen a palace full of light, and – overwhelmed by the miraculousness of everything from a soul to a star – asked “Doesn’t this place belong to someone?” God had long been waiting for someone to recognize the brokenness of the world and its possibilities for tikkun, for healing and hope. Abraham was the first to fully feel it. For all of us engaged in fighting for a better, kinder, world the lesson is manifest: seeing both the anguish of the world and its enchantment enables us to move from a palace on fire to one filled with light.

Why build a tower of babel? The question has received many answers. One in particular is crucial for our world.

Rabbi Obadia Sforno, born in the late 15th century in Italy, argues that the tower was intended to unify the world in a certain practice of idolatry. This explanation may be a product of the world in which Sforno lived, but it also has a great deal to say to our own world.

15th century Italy, unlike anywhere else in Europe, was divided into independent city states. Therefore, it epitomized a condition already present in Europe in general, which is a distribution of authority.

Historian Jared Diamond makes this point about Columbus. Columbus first approached the rulers of Portugal to fund his voyage and they refused. Had Columbus been part of a single empire like that which prevailed in China, a first refusal would have been final. But he lived in Europe, where each country had its own government. Having been turned away in Portugal, he went next to Ferdinand and Isabella in Spain. They, along with private funders who also had a measure of autonomy, agreed and he set sail.

Sforno understood the power of plurality and diversity from his home in Italy. He also understood the temptation of totalitarianism. What is God’s solution to the building of the tower? Enforce diversity by breaking the people up into different groups with different languages.

Throughout history people have dreamed of making humanity conform in culture or language or politics. The 20th century built such “perfect places” with the ideologies of fascism and communism. We see such ideologies continued or revived today – people who insist others think and live as they do.

Judaism has long absorbed this lesson; it is a monotheistic faith that does not demand that others join our faith. Judaism asks others to be good, not to be Jewish. As the Rabbis teach, the stamp of human coins are identical, but the Divine stamp makes each individual unique. From the time of the tower we have recognized that God seeks human beings with diverse outlooks and gifts, to create a varied and multicolored world.

We are a society fond of novelty but we know that mastery demands repetition. No one is a great golfer with the first stroke, or a grandmaster with the first move of a pawn. Human achievements, individual and social, require constant application. We cannot grasp depth on the first pass: “There are no readers” said the writer Vladimir Nabokov, “only rereaders.”

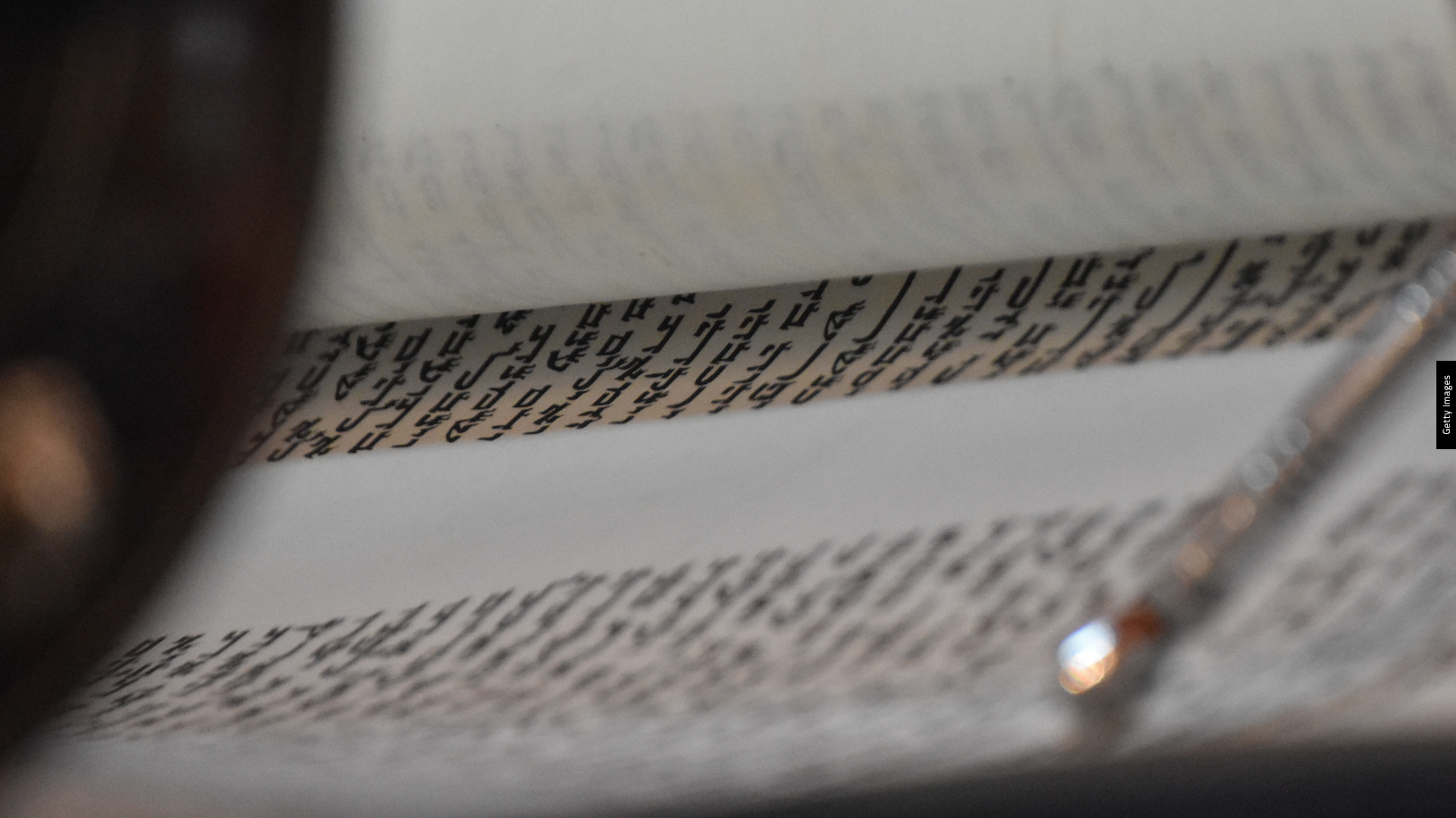

The Torah has been described in many ways: a love letter, a ketubah, one long poem, a mystic message of black-on-white fire, a compendium of law and story, a family diary, the foundation stone of Israel, a written assurance of God’s love. All of that cannot be grasped at once; it unfurls its secrets over time. Turn it over and over, the Rabbis advise us, for everything is in it.

This week is Simchat Torah, the celebration of the reading of the Torah. It is traditional to dance with the Torah, joyous to once again be receiving this gift. We recommit to learning and renewing our understanding.

In order to do that, we must also renew our efforts to protect it and those who treasure it. Two years ago on Simchat Torah, as we danced in streets of Los Angeles, an Iranian woman approached me with tears in her eyes. “Growing up in Iran never would have dreamed the day would come that I could dance in the street with a Torah.” Rereading the teachings of human sanctity and worth, we reinvigorate our commitment to ensure that dignity for others.

To have great books, said Walt Whitman, there must be great readers. For thousands of years the Torah has been the focus of scholars, saints and sages, the distilled genius of the Talmudic Rabbis and their innumerable disciples. Words seemingly wrung dry by intellectual exertions suddenly show themselves capable of new meanings to new generations.

This year on Simchat Torah as we hold aloft the Torah, we can make the words come alive again. Readers are those who not only go through the text, but allow the text to move through them. Holding aloft the Torah we understand the mission to see its words realized in our lives and in our world: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land, to all the inhabitants thereof (25:10).”

This has been a year of tremendous trauma. I have come to believe that Sukkot is the PTSD holiday. In several ways it is designed to address the trauma of our lives:

- The Hebrew name for Egypt, Mitzrayim, is associated with narrowness, “tzar.” After the constriction of slavery and the inability to escape, comes Sukkot. In the desert, there is space. The sukkah is un-claustrophobic by its nature. Since there is no covering on the roof, you can see the outside. You are not hemmed in, which is one of the triggers of trauma. This is what we pray for our hostages to experience again, and soon.

- The Rabbis say “sukkah” refers to the sukkah of clouds that God provided for the Israelites as they walked through the desert. Being taken care of, a gentle shade over your life, is calming after the brutality of Egypt. Fear is soothed by caretaking.

- The sukkah reminds us that we are not alone. Not only do we invite other people into the sukkah, but traditionally we also bring in the ushpizin – historic figures from the Jewish past who share our history and gave us their dreams. The vision of the stars above is a further reminder of God’s presence. As Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo: “I feel a tremendous need for religion, so I go outside at night to paint the stars.”

- Like a mikveh, the sukkah is done with one’s entire body. As we have learned – particularly in the classic work on trauma The Body Keeps the Score – trauma is stored in the body. Also on sukkot we build something. Creating helps heal.

- Sukkot is the only holiday whose name is an emotion – Z’man Simhatenu, the time of our joy. Trauma robs joy. Sukkot encourages us to feel joy, reminding us that it is good and healthy to be happy. This holiday that returns us to nature, to greenery and the elements, lifts our spirits. It has been an awful year. Sukkot can help bring us back to wholeness.

Jewish tradition pairs the holiday of Yom Kippur and the costuming holiday of Purim. It seems a strange pairing, but in fact the biblical name Yom Kippurim can be translated as “A day like Purim.” There are many explanations of the connection; Rabbi Jack Riemer explains that on Purim we put masks on and on Yom Kippur, we take our masks off.

We all wear masks, professional and personal. Yom Kippur is the day when we explore ourselves and our own souls. It is a time to be ruthless in self-examination: To ask ourselves, what bitterness do we harbor in our own hearts? Especially in this past year, we have been so busy combatting the ugliness in the world we do not always have time to turn inward.

Yom Kippur arrives at a very fraught and painful time this year. But as we beat our chests, a kind of spiritual defibrillator, all of us are seeking to awaken our hearts to balance resolution with compassion, anger with understanding. There is a line of the poet Yeats that I have often thought of since last Oct. 7: “Too long a sacrifice makes a stone of the heart.” We have seen a great deal of sacrifice this year, but we will not let it make our hearts harden. Judaism asks just the opposite, in fact: it is no coincidence that some of the greatest warriors of Jewish history – King David in the Bible and in the Samuel ibn Naghrillah in the Middle Ages (d. 1056) – were also poets.

Yom Kippur reminds us that the task of life is not only to make the world better but to make ourselves better. What mitzvot, acts of connection to people and to God, can we undertake this year? When have we lacked clarity, decency, courage? On this day we have a moment to breathe and to reflect.

The Kotzker Rebbe once screamed at his disciples: “Masks! Where are your faces?” Yom Kippur is a day to see one another panim el panim – face to face. It is a time to deepen relationships, repent of wrongdoing and look up to what is greater than ourselves. There is a great deal of work to be done in the world. In the year to come we will confront enormous challenges and combat deep seated hatreds. Let us take this day to open our hearts, reveal ourselves, and elevate our souls. May we be inscribed in the book of life.

In recent years a movement has arisen entitled “effective altruism.” It is an approach to charity that has won a number of adherents, but its central principle is not only old, it is found in today’s Torah portion.

Effective altruism argues that we owe a debt to the unborn that is in many ways no less than the debt we owe to those standing next to us. This is something we already recognize in many of our actions: policies involving research for example, that are intended to pay benefits in the future, even if we don’t live to see it.

In the parashah today Moses tells the people that the covenant is not only made with those who stand there on that day, “but also with those who are not here with us (Deut. 29:14).” Moses is saying to the people that future generations down through the ages are part of the covenant as well.

Judaism has always embraced the ideal of charity toward the future. Famously, the old man in the Talmud Ta’anit 23a who is planting a carob tree he will never eat from, explains that it was done by his ancestors for him. Moses, like Herzl, leads people to a land he will not himself inhabit. Jeremiah buys land in Israel as the people are being exiled in the hope of future return. Generations of Jews learned to see themselves not only as inheritors but as ancestors. We hold in sacred trust for those who follow.

When in our day we confront the evils that arise, proclaim the values we cherish and embrace the allies we esteem, it is not only so things will be better today, or tomorrow. Our efforts to fight for what is right, so painful in this year of anguish and loss, are also pointed toward the future, sometimes even the far future, when those we shall never know will eat the fruits we plant today. Do not despair, Moses is teaching the Israelites. You may see difficulties and trials despite being part of the covenant, despite all your efforts, in contradiction to your hopes. But the effort you make is not only for those who stand today but those who are not yet here. Yes, it has been a dispiriting year. Yet when the labor appears thankless, remember that our struggles are not only for ourselves but for both Jews and non-Jews who will be blessed by everything we managed to accomplish, just as we have been by those who stood at the mountain thousands of years ago.

Sixty-three years ago, President John Kennedy famously proclaimed, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Recently I visited West Point to speak at “Warriors Weekend” – which gathered Jewish cadets from all the armed services of the United States. Filled with young people who were asking that very question, we gathered in the chapel. The small building features a Torah saved from the Holocaust and the names of people who heroically served, and together we talked about Judaism, about life and about commitment.

As I spoke to the men and women in uniform I recalled the beginning of this week’s parasha: Ch. 26:1,2: “When you have entered the land the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance and have taken possession of it and settled in it, take some of the first fruits of all that you produce from the soil of the land the Lord your God is giving you and put them in a basket.” In other words, when you inherit the land the first thing you must do is give something in gratitude for what you have inherited.

American law is built around rights. Jewish law is built around obligations. Each has its place and worth. Yet when either becomes the only criteria, society falls apart. Throughout the history of Jewish law there has always been consideration for what rights the person has and what freedoms under the law obtain. For too many Americans however, the concept of “what I am free to do” has become almost the sole way they understand their relationship to America.

For a variety of reasons, volunteering in America has dropped steadily over the last several years, and charitable giving has also declined. Yet many of us are still called, as the Torah instructs, to help in myriad ways. Standing before those cadets, I felt a renewed sense of the inspiration in their commitment to a cause.

Those of us who are engaged in the fight against prejudice and hatred understand that to engage in this campaign requires deep commitment to the same ideals as those young people. We ask – what can we do for our nation and for our people? The answer? As the prophet explained it three thousand years ago, we seek a world in which “Everyone may sit beneath their own vine and fig tree, and none shall make them afraid” (Micah 4:4).

How does the prophet respond when the people are suffering? Isaiah says, speaking in God’s name: “For a moment I hid My face from you, and with everlasting kindness will I have compassion on you (Isaiah 54:8).” Our hearts remain burdened with grief for the hostages who were murdered and one of the places we turn for understanding is to our ancestors, who again and again endured the pain of persecution and loss.

So how did the sages who came before us, who also suffered unimaginable losses, understand this verse? I looked at the commentaries and found a recurrent theme. In every generation, from rabbinic times until today, commentators acknowledge the pain expressed by the first half of the verse. For a moment, God is – or at least feels – absent, and in that dark void the most terrible things befall us. Where was God in the camps or in the tunnels? There is no fully adequate response. Sometimes we ask these questions not to elicit answers, but to express anguish.

Yet those same commentators turn to the second half of the verse and affirm it as well. Yes, the pain is real, but so is the promise. We will always feel the loss. That loss will also permit us to understand things that move us forward: As Rabbi Johanan points out in the midrash, our eye has a light part and a dark part, but we can only see through the dark part (Midrash Tanchuma, Tetzaveh 6:6). In failure, loss and grief, in God’s hiding, we often see more clearly; we glimpse our deepest concerns and most fervent loves.

The Jewish world is in mourning. We are mourning for Carmel, Eden, Hersh, Alexander, Almog and Uri. We are in mourning for all of those killed and wounded and their families and for the devastation in the aftermath of Oct. 7. There are no words that can make the pain disappear. No reassurances will shake the feeling that, for a moment again, God’s face was hidden and darkness grips the world.

This passage from Isaiah is called the “Fifth Haftorah of Consolation” – the fifth in a series of seven between Tisha B’av and Yom Kippur. The prophet recalls us to the challenges and afflictions our people have known in the past. He shares in the reality and depth of our pain. And he offers the consolation that this pain may be consuming right now, but the pain itself proves our compassion, and turns us toward the hope of God’s promise that endures.

May the memory of those we have lost be a blessing and give us the strength to be God’s partner in the sacred task of combating hatred and bringing light to the world.

There is no obligation to have a favorite biblical verse. In the Talmud a couple of Rabbis identify favorite verses but most do not. If I had to choose, I would select a verse from this week’s parasha, Deut. 4:9 – “Guard your soul carefully.”

This verse has grown in importance in our own day, although it was always a crucial reminder given the snares and distractions of life. I’d like to suggest three ways we need to learn to guard our souls better in this world.

- The overemphasis on bodies. Culturally we are worshippers of the physical. We are bombarded by diet advertising and advice, exercise regimes and health regimens, and then shamed if we do not conform to this or that standard. If it were all in service of health, it would at least be understandable. But we idealize certain body types and foist them through social media on our children. We have become so focused on physicality that the soul languishes. Seemingly all that matters is how your picture plays on social media. You cannot put your soul on Instagram.

- The desire to win at all costs is a snare to the soul. We will not admit mistakes or regret, because it disappoints our own “team” and gives aid and comfort to the “enemy.” Polarization is not about the integrity of the soul but the triumph of the ego. Each lie and omission and evasion corrodes our souls.

- Finally silence. In the months since October 7th the Jewish community has been often disappointed by the silence of those for whom we raised our own voices in the past. Even some Jews have shied away from proudly proclaiming both their tradition and their solidarity with Israel. Each time you are cowed by the mob and refuse to speak what you know to be true, you are betraying the promptings of your own soul.

The Torah is a guide for life. No teaching, however wise, can guard your soul without your own care and effort. We were given but one soul as we move through this life – guard it carefully.

Before Israel enters the land, Moses recounts their history. He discusses the wandering, the gathering at Sinai, the episode of the scouts and much more.

This parashah of the Torah, devarim, is always read before the commemoration of destruction on Tisha B’av. The Shabbat, because of the haftorah reading from Isaiah, is known as Shabbat Chazon, the Sabbath of a vision. The title is taken from the first words of the book in which the prophet’s vision is introduced.

In one Shabbat we read of a look back and a vision of the future. What has all of this to do with Tisha B’av which is arriving this week, and the parlous state of Israel and the world today?

For a modern parallel, look to Israel’s declaration of independence. Before enunciating the vision of the new state, it recounts the ancient attachment of the people to the land, and the travails that kept Israel from its birthplace. In other words, when building the modern state, our people chose the ancient example: recount the past and then offer the vision.

The vision arises in part from the pain of the past. For ancient Israel, wandering in the desert drove their desire for the land. In modern Israel, the centuries of exile strengthened the resolution to fight for our homeland.

There is a tradition that the Messiah will be born on Tisha B’av, the saddest day of the Jewish year. For the sorrows of the past are a prelude. From the moment we stood on the second bank of the Jordan, Jews have believed that from sadness will spring joy. We recount the story of the past because it is the past that impels us to seek the redemption of what can be in the future.

Right now the pall of Oct. 7 and all that followed still hangs heavily over Israel and indeed over the world. Our task is to recount those events, but also to offer a vision of how the pain of the past can yield to the promise of the future. The history of Moses leads to the vision of Isaiah; the destruction of the Temple presages the birth of the Messiah; the years of diaspora lead to the declaration of Independence; and we pray and work to ensure that the agonies of Oct 7 and the war will impel us to a new vision of a strong and safe Israel and Jewish people, in a more peaceful world.

After the final campaign east of the Jordan river, the nation is ready to advance into Israel and enter the Promised Land.

But there are two, eventually two-and-a-half, tribes that want to stay in the land they have recently conquered. They recognize the delicacy of the request. Israel is the Promised Land and they are willingly absenting themselves. What follows is a subtle but beautiful example of what it is to ask, and what it means to listen.

The Gadites and Reubenites approach Moses, Eliezer the priest and the chieftains of the community (Numbers 32:2). We are told, “and they said.” This is followed by a recounting of the names of the lands they have conquered and the information that this land is “cattle country and your servants have cattle.”

The next word (ibid. 32:5) is “Vayomru” – and they said. The text continues, “It would be a favor to us if this land were given to us....” Why is “and they said” repeated twice in the same speech?

Ibn Ezra (d. 1167) says repetition is to remind us that they are still talking. But other speeches in the Torah do not repeat “and they said.” It also fails to explain a significant feature of the text – the letter samech in the Hebrew separates the two phrases. Why should there be a break here in the middle of a speech?

Abravanel (d. 1508), who served in the government of Ferdinand and Isabella and was doubtless involved in many negotiations, offers a deep explanation that reflects his experience.

Abravanel notes that the opening of the speech is a sort of veiled request. They are saying – you know, we have a lot of cattle, and this land is perfect cattle land. Then they fall silent. The tribes are hoping that Moses will himself come up with the idea – why, then you should just stay here! They are trying to escape the responsibility of their own decision.

The samech, says Abravanel, represents Moses’s silence. “And they said” is added again because after the silence they resume speaking and this time make the request explicit.

Moses then reminds the tribes of the struggles of the past. They promise to fight until all of Israel is secure before they return across the Jordan. Under those conditions, they are allowed to keep the land.

Moses demonstrates how to listen and demand responsibility of the questioner. But more important, the exchange emphasizes that we who remain outside the land must work to ensure the safety of those who dwell there.

After Oct. 7, we understand Moses’ silence in a new way. We too passionately promise to aid our sisters and brothers in Eretz Yisrael, as our ancestors did on the plains of Moab.

Tuesday is the 17th day of the month of Tammuz. For many Jews this date holds no significance, but in Jewish history and observance it matters a lot. And I recently had two experiences that reminded me anew why this day is so significant.

Five calamities are said to have occurred on that date, the most important being the Romans breaching the outer walls of the Jerusalem. Three weeks later the Temple was destroyed, a catastrophe commemorated by Tisha B’av. The 17th of Tammuz is a minor fast day. Why should we fast for the beginning of the end of sovereignty two thousand years ago?

On a recent visit to Israel, I toured the soon to be opened National Campus of for the Archeology of Israel. This remarkable new building will hold and display some of the most important archeological treasures in Israel and indeed in the world. Recently uncovered were intact Roman swords, unique in the world, with scabbard from wood and handle of leather and blades still strong. Found in a cave in the Judean hills, they were taken by Jewish rebels from Roman soldiers and hidden for the revolt; and you can see them before your eyes.

Later that day I flew up to the Technion, Israel’s premier institute of science and technology. There I met with several remarkable students, all in their twenties. Each of them has lost months from study to serve on the front lines in Gaza and the North. They have buried their friends and seen them injured. One, who lived with his family in a border kibbutz, barely escaped on Oct. 7 with his family.

These brilliant young men and women, who dream of innovating in computer science and cancer research and aerospace engineering, are spending their time carrying rifles, the modern equivalent of swords, into battle to protect the land they love. If you ask why the ADL fights against hate, we do it in part for them.

Rebels trying to take back their land from the Romans two thousand years ago; students trying to protect their land from terrorists today. The line of Jewish love for the land is unbroken as is the willingness of our people to sacrifice for safety and sovereignty.

As I flew back from Haifa along the coast and saw Roman ample theaters and crusader ruins, I thought about the 17th of Tammuz. And about October 7th. This Tuesday, whether you fast or not, spare a thought and a prayer for those who fought thousands of years ago and those who fight today.

Am Yisrael Chai.

The Israelites have been wandering for a long time. Why does the rebellion of Korach occur now in the biblical story?

Rabbi Baruch Epstein, the author of Torah Temimah, in his commentary Tosefet Bracha, explains: There were always dissatisfactions, but the people held them in check for they had a great expectation. They were about to enter the land. In last week’s Torah portion, however, the spies returned with their evil report. God’s wrath was inflamed and God spoke through Moses. “In this very desert shall your carcasses fall. Of all you who were recorded in your various lists from age 20 and above, you who have muttered against Me, not one shall enter the land that I swore to you, save Caleb son of Jephuneh and Joshua son of Nun” (Numbers 14:29-30). They will not enter the land as they had hoped.

Hope deferred, Proverbs teaches, makes the heart sick (Proverbs 13:12). The disappointment led the Israelites to push against the leadership of Moses.

In his famous poem “Harlem,” Langston Hughes asks what happens to a dream deferred:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore

– And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over

– Like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

Like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

The dream of going into the land was not only deferred but denied for the Israelites. And as the poet teaches, it explodes. This linkage also helps explain, writes R. Epstein, the answer to Rashi’s question. Rashi asks why the Torah places the story of the spies and the story of the rebellion back to back, since it is a scriptural principle not to juxtapose two catastrophes. Rabbi Epstein’s answer is that one essentially caused the other.

Part of the heartbreak of the current war is to see the hope of peace snatched repeatedly throughout Israel’s history. So often we had thought peace might be within reach, only to see it violently denied. But like the Israelites who did eventually enter the land we have to renew hope, despite discouragement, and work anew toward peace.

Rabbi Abraham Twerski recounts how his parents used to discipline him. They would not say “You are not good.” They would not even say, “What you did is not good.” Rather, explains Rabbi Twerski, they would say, “What you did is not worthy of you.”

This is the Jewish way. First you affirm the essential dignity of the human being and only then may one criticize. The Torah is filled with the misdeeds and depredations of Israel and the surrounding nations. But what is the first statement about human beings? That we are all in the image of God. Dignity first.

When in this week’s Torah portion the spies enter the land of Israel, ten of them return believing that the land is beyond their grasp. They have been so beaten down by the experience of slavery and the difficulties of the wilderness that they forget their own worthiness. Only two of the spies, Caleb and Joshua, remember the lesson of Sinai: a people that merited standing before God need not cower or believe themselves unfit. Joshua was originally called Hoshea and his name was changed from Hoshea to Y’hoshua. The addition of a yud, which represents God’s name, was added to the man who would become leader of Israel after Moses. Therefore Joshua only had to recall his own name to recognize that he was in God’s image.

The Rabbis teach us something beautiful and poignant about that “yud.” Where did it come from? Sarah was originally Sarai. God took the yud from her name and replaced it with a heh, which is also a reminder of God. Then God gave the now extra yud to Joshua. This beautiful midrash also has a serious message: it reminds us that knowledge of the image of God is transferable. Parents can teach it to their children, and we can teach it to one another. Our essential endowment remains, even when we do not recognize it ourselves.

When we do remember it, however, we diminish hate and make the world a better place. Every human being is in the image of God. Dignity first.

The title word of the book Bamidbar (In the Wilderness) is connected by rabbinic tradition with dibur (speech). The book and the word intertwine; portable cultures rely on words.

The desert brings a range of speech: First there is the speech of complaint, the ancient kvetch. The Israelites are unhappy with the manna and demand meat. According to the Rabbis, the manna could taste like whatever one wished, so why would they complain? An acute suggestion from R. Jonathan Eybeschutz explains that everyone collected the manna equally. Therefore, no one could be better than his or her neighbors. They claimed to be upset about food, but what really bothered them, even in the desert, was social status.

The other instance of social status masquerading as complaint in the parasha is the gossip of Aaron and Miriam about Moses’s wife. For right after the complaint about his wife (12:1) they said, “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has he not spoken through us as well?” Behind it sound echoes of: “Mother always liked you best.”

This illustrates a reality about gossip. People rarely gossip about those they consider their social inferiors. Employers do not gossip about employees, but employees do about employers. Part of gossip is reducing the status, moral or social, of the one derided. Once again, as with the manna, negative speech is about social status.

Then there is the unelaborated but important speech of Eldad and Medad, two men who are prophesying in the camp.

In response, Joshua complains that the two are offering prophecies. Moses gives a famous answer wishing that all God’s children would be prophets. This is the speech of humility.

We just celebrated Shavuot, when we rejoice in the giving of God’s words. The words of human beings can also change the world.

Now that Israel has received the words of God at Sinai, their education will be in the use of words to uplift, not to destroy. We cannot achieve prophecy, but we can aspire to decency. We can speak words of kindness and love, not of hate. For life and death, as Proverbs teaches us, is in the power of the tongue.

The Israelites stood at Sinai. There was thunder and lightning and the sense that something epochal in history was unfolding. To this very day what is called the revelation at Sinai is central to Jewish tradition and the ten commandments are central to the world. What precisely was revealed that made so much of a difference?

There are many ways to answer this question but let me suggest one: In the ancient world, as we see when we read Homer or other myths, how the gods felt about you depended upon how you treated them. Give them what they want and you will be favored.

The first part of the ten commandments seem to follow the same pattern – there is one God, do not make other images of God and so forth. But suddenly it shifts to how one treats parents, how we treat those we love, how we treat our neighbor. The great revelation becomes clear: God does not only care about our attitude toward God; God cares how we treat one another.

The ten commandments were given in the desert, and not in Israel, teach our sages, because they are for everyone to hear, not only for Jews. The great principle that is born at Sinai has become so fundamental we barely realize that it had to be born into an unwilling world: all people are in God’s image and honoring that in one another is the most important way to honor God.

Shavuot is not a holiday with the same kind of memorable signs that characterize Passover or Sukkot. We do not have a Seder or a Sukkah. The primary custom associated with Sukkot is to stay up late and study. If Passover is about freedom and Sukkot about appreciation, then we might say Shavuot is about understanding. Into a world of savagery and indifference, where human beings were exploitable commodities, Judaism taught a new understanding, born at Sinai. Our efforts to combat hate in the modern world are an advancement of this understanding: “You should love your neighbor as yourself for I am the Lord (Lev 19:18).” So revolutionary an idea takes thousands of years to fully grasp, and we are still trying. On this Shavuot we commit ourselves to understand anew and to struggle for the recognition that kindness to human beings is a reflection of our gratitude to the One who created us. Chag Sameach.

Anti-Memoirs, the autobiography of the French writer, adventurer, and critic André Malraux, begins with a very pointed story. During the war, Malraux once escaped the Germans in the company of a parish priest. When the two cross paths years later, Malraux asks his former companion what he has learned about human nature from a decade and more of hearing personal confessions. Two things, the priest replies. First, that people are much unhappier than one would think; second, “there is no such thing as a grownup.”

The first verse of the book of Numbers is: “The Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai.” In giving the book its Hebrew name, Bamidbar (in the wilderness), this opening sentence reminds us that the Torah is a tale of the wilderness.

The setting conveys the first lesson of Malraux’s priest, that the world is itself often a place of unhappiness. Judaism is a tradition to be lived and observed amid all of life’s difficulties and harshness. Even when the Israelites enter the land, they won’t find a perfect, blissful environment.

They must be prepared.

Why do we need so rich and wise a tradition? Here we come to the second lesson of Malraux’s priest: there are no grownups.

The language of Scripture testifies to this message by consistently calling the people “the children of Israel.” That is true in a literal sense: they are the descendants of Jacob, who is also called Israel.

Also, they act like children: rebelling, refusing, ungrateful, self-centered, often immature—and thus constantly in need of education and moral guidance.

In focusing on the infancy of Israel’s collective history, the Torah tells us that all human beings are children of the wilderness. Seen in this light, the book of Numbers is a story of moral education, and one whose lessons can be applied to anyone’s quest for self-betterment.

From the moment humanity steps out of Eden, the Torah makes clear its unremitting realism about our condition, telling us time and again that pain is inevitable and that growth is at once demanding and essential. In the book of Numbers we are also shown the conditions that make the journey bearable and sacred: the existence of a map through the wilderness that we call the Torah and a Guide, our Creator, to point the way.

Mark Twain, whose manuscripts are nearly illegible due to all the changes and revisions, once wrote, “the difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter, ’tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

For a word to be lightning it does not need to be long. In this week’s Torah portion the 19th century sage, Mei Hashiloah, Rabbi Mordecai Yosef of Izhbitza, focuses on two letters, the word “if,” which begins the portion: “If you walk in my ways.” (Leviticus 26:3) He explains that “if” signals the uncertainty of one who seeks to follow God’s ways, for “the will of God is very deep.”

The more we explore “if” the more lightning we find in the word. “If” in Hebrew is (אמ) im and contains all possibility in it. “If this had happened.” “If that had not happened.” “If I had said this.” “If I had not said that.” But the word im contains an even greater power in Jewish history.

“Im” is spelled aleph mem. The Mincha Belulah (16th century) teaches that in liberation, there was an im – an if. The name Aaron begins with an aleph and Moses with a mem. So too with Purim: Esther begins with an aleph and Mordecai with a mem. Finally, Eliyahu, the herald of the end times, begins with an aleph and Moshiach, the Messiah, begins with a mem. The aleph and mem of im carry within them past and future redemption.

“If” contains all of life’s regrets. But even more, im is a word of possibility. God says, “IF you walk in My ways.” We hold the im in our own hands.

One of the best loved poems in the English language was written by Rudyard Kipling for his son. It is called “If.” It’s worth reading the whole poem – here is a part:

“If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too…

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And – which is more – you’ll be a man, my son!”

“If” is in your power – you can change your life. God gives us the power – and the choice.

The Torah never fails to admonish us about idols. Again, in this week’s parasha we are told not to set up idols. We understand that idols are a kind of substitute God, and therefore it seems like we are insulting God by worshipping other gods, particularly when they are the products of our own hands. But I want to suggest two more ways that idols are dangerous – by making us too important and by making us too insignificant.

Idols contribute to our sense that we can channel the great forces of the world and control them. We make idols in our own image: idols are usually similar to human forms and figures. It is as if we create representations of ourselves and then venerate them.

But idolatry also gives us too little credit. Abraham Joshua Heschel once taught that idols are forbidden not because they insult God, but because they insult us. There already exists in the world an image of God. It is in each human being. Therefore, the medium through which one fashions a genuine image is the medium of one’s life, by sacred acts. To carve a piece of wood and call it God is to belittle God and to belittle the spark of God inside of us.

As images of God we are given a sacred task. The canvas is existence; a mitzvah is a brushstroke; we are instructed to make of our lives a work of holy art. Rather than carve artistic ornaments from the material of the world and bow to them, we fashion goodness, godliness, for the stuff of our souls.

Rabbi Akiva taught in Pirke Avoth that we are loved for we were created in God’s image. But an even greater love is reflected in God’s telling us that we were made in the divine image. With such a privilege, why fashion idols? Instead, we should learn to see each other as individual sparks of the One who created us all.

During these days, Jews count the “Omer.” The Omer marks the 50 days traveling the desert from Egypt to Sinai. Beginning the second night of Passover we count each day until the holiday of Shavuot, 50 days later, when Israel stood at Sinai to receive the Torah. Jews follow the practice of counting each evening, and there are many spiritual and mystical significances given to the days.

The Omer also has agricultural significance. It recalls the wave offering of the Temple on the second day of Passover. The wave offering was a measure of flour made from the first sheaves of barley grain that had been reaped.

The late Chief Rabbi of Israel, Isaac Herzog, writes that the Talmud regards barley is a maakhel behema, a food fit for beasts. Why do we offer animal food in the Temple? Could it not be construed as an insult to God?

We know, he continues, that human beings share many things with animals. From a certain perspective we are a link on the biological chain, and nothing more. As with all of nature we are governed by our physical natures. Yet human beings can act against impulse, and behave in ways that refuse to permit our impulses to control us. Judaism teaches that it is often our task to rise above animality alone and to realize our higher natures.

Nature is, in the famous phrase of the poet Tennyson, “red in tooth and claw.” Violence and cruelty is part of human nature too. Yet according to the Talmud, the purpose of the mitzvot – the entire system of Jewish law – is to refine human beings. That which begins as an animal instinct can, through the guidance of Torah, be lifted to embody an expression of the Divine. The barley offering is a food for animals, but sifted and refined, it can be offered to God. We too begin with an animal nature but the Omer represents the aspiration to ennoble instinct, to recognize that we are indeed animals, but we are not only animals. Sifted and refined, day by day, we are worthy to approach God.

Rabbi Akiva identifies a problematic verse as the most important one in the Torah: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18).

Parashat Kedoshim contains a number of laws, but it is revealing to note what immediately precedes the admonition “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” The beginning of the verse is Lo tikom v’lo titur (Do not take vengeance or hold a grudge against others).

If you are not to hold a grudge, what ought one to do? When someone commits an offense against you, the alternative to holding a grudge is forgiveness. We are all aware that forgiveness is, to say the least, a difficult task. The advice of the Talmud is not easy to follow: “Be of those who take an insult but do not give it. Hear their reproach but do not reply” (Gittin 36b). There may be offenses for which forgiveness is not possible. Yet we live increasingly in a society where forgiveness is not given for almost any offense, and words that one speaks can result in being publicly reviled or “canceled” with no apparent path to restoration.

This is not only ungenerous, but a narrow view of the purposes of forgiveness. We do not forgive other people only for their sake. As has been said- to hold a grudge against another is to swallow poison planning for it to kill the persons next to you.

The verse that precedes loving your neighbor tells us, “Do not hate your kinsman in your heart.” It is one of the very few places where the Torah commands emotion. But we can now understand that it does so for our own good, because hatred not only imperils community, but it embitters the life of the hater. One way of understanding the famous verse that follows is – love your neighbor, forgive your neighbor, for that is one way of learning to love yourself.

It is a lesson our society needs to learn.

Throughout Jewish history, the Passover has operated on two levels of time. The Haggadah recounts the past, the story of both the Exodus and the Talmudic Rabbis who expound on it. The words make all of the ideas come alive for the participants: slavery, freedom, study, storytelling, song and symbol. Passover is quintessentially a celebration of the events of the Jewish past.

At the same time the Passover is about the present. In medieval times Jews felt their predicament as parallel to their ancestors, and the despotism and persecution with which they lived lent power to the tales of the Haggadah. Closer to our own day I remember my parents telling me when they visited the Soviet Union how the Jews trapped behind the iron curtain felt the Passover was about them. In the struggles of the slaves they saw their own struggles; in the character of the Pharaoh they saw their communist oppressors; in the story of liberation they saw their own hope. The Seder was not a meal about what was, but what is.

As we sit down to the Seder this year, we have the same experience. In our own day the Seder is about the liberation from Egypt, but also about the hostages in Gaza. We recall the fear expressed in the time of the plagues but each moment also recalls us to the violence and brutality that our sisters and brothers in the land of Israel both experience and fear today. The Seder is again the story of what was, but also the story of what is.

We are told in the Haggadah that in each generation one must see oneself as if we went forth from Mitzrayim. The reverse is also the case. In each generation we must see Mitzrayim as it surrounds us today.

This year we remember those among our people who are in captivity. As we recall the trials of our people in ancient times, we pray for the liberation of our people in our own day. In every generation there have arisen those who would destroy us. And in every generation we have arisen to fight, to remember, to pray and tell the story.

In Leviticus, Aaron is ordained as the High Priest. This week we are told (Leviticus 9:1): “On the eighth day, Moses called Aaron and his sons and the elders of Israel.” Why was the eighth day chosen?

Eight is a time for renewal. Seven represents fullness, completeness. There are seven days to creation, seven days to a week. Then comes the eighth.

When a male is born in Judaism, after a week the brit milah signifies a new beginning as one ushered into the covenant of Israel. Conversely, when someone passes away, the mourners sit shiva, literally seven, before they begin a new phase of life, one without the physical presence of the one whom they loved who has died. Each, the onset and the end of life, envision the eighth day as a starting point.

The holiday of Sukkot concludes with Shemini Atzeret, the eighth day of gathering. It concludes with Simchat Torah, the reading of the Torah – the new beginning, Genesis.

Before the bride and groom come under the huppah, it is traditional to have the bride circle the groom seven times (in these days, sometimes three, three and one). That is completion, and now they are ready to take the eight step toward a new beginning.

Aaron begins on the eighth day because he must begin again. He failed with the golden calf and will know tragedy with the death of his sons. Rashi explains that the public announcement is so that people know God has chosen Aaron despite the golden calf.

He begins again. Moses too has known multiple frustrations, disappointments, and failures. He and Aaron will nonetheless renew themselves to continue to lead Israel’s march through the desert. Eight is the promise that shortcomings are not the final word.

We celebrate new beginnings. Yet the power not of beginning, but of beginning again, is a secret to survival. The community of Safed created vibrancy from the ashes of the Inquisition, American Jewry from those who fled Europe before the wars, and countless events in the history of the Jewish people down to our own day and the founding of the State of Israel.

Many peoples in history have lived their term and disappeared; they could not exceed seven. We seek to be the people of the eight. Beginning anew is the way of spirit.

Anyone familiar with a Jewish wedding has to be shocked by the reading from this week’s haftorah. The prophet Jeremiah declares bleakly to the people in God’s name: “Then will I silence, in the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem, the voice of joy and gladness, the voice of the bridegroom, and the bride: for the land shall be desolate (7:34).”

Jeremiah’s words made sense in his time. He lived in a tumultuous age when the Assyrian empire declined and the Babylonians arose. Israel was defeated by the Babylonians and went weeping into exile. There was no joy in the streets of Jerusalem. It was a time of loss and deep despair.

So it is very strange that we quote the prophet at a wedding! What do we sing as we chant the sheva brachot, the seven blessings? “Again will be heard in the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem, the voice of joy and gladness, the voice of the bridegroom, and the bride.”

We take the despair of the prophet and with a phrase, turn it to hope. There is an even more famous example of this reversal in Ezekiel. In chapter 37, the famous vision of the dry bones, Ezekiel pronounces “avdah Tikvateinu” – we have lost our hope. That phrase may sound familiar. The second verse of Hatikva, the national anthem, begins “od lo avdah tikvateinu” – we have still not lost our hope. Once more, the words of the prophet are turned from anguish to inspiration. We know that better days will come and we refuse to be dispirited.

In these difficult days when we fight a rising tide of hate there is an impulse to believe that our efforts are in vain and our future bleak. But every time we sing at a wedding, each time we rise for Hatikvah – indeed each time we seek to transform enmity to acceptance and hatred to love – we are practicing the wisdom of our tradition. As the Psalmist taught us thousands of years ago, “in the evening there will be weeping, but joy will come in the morning (Ps. 30:5).” Take heart – there shall be joy in Judah and laughter on the streets of Jerusalem.

Purim is a holiday of masks. A mask doesn’t fully change you, but it obscures identity, distorting who you are. The boy who dresses as Mordechai can act old and wise, but everyone recognizes him as a boy playing a role; the girl who dresses as Esther can play at being bold, heroic and a queen, but everyone knows she is still a little girl.

There are many reasons why Purim is associated with masks, but surely a deep meaning is that it is a diaspora holiday. Purim takes place in ancient Shoushan, Persia. The plot revolves around Haman, who hates the Jews. The reason given is that Mordechai, a Jew, will not bow down to him, but the story implies that Haman’s rage is what we have come to know as classic antisemitism – a hatred in search of a rationale.

In the diaspora, Jews were forced to wear masks all of the time. In Muslim lands we were dhimmi, second class citizens subject to a vast range of indignities and periodic persecutions. Since we were powerless to change it, we wore the mask of acceptance and accommodation. In Christian Europe, Jews were regularly exiled, oppressed, targeted for conversion and sometimes killed. But in country after country we donned the mask of the willing subject, because rebellion only made it worse. The few who did not wear a mask, the Mordechais who did not bow down, paid a terrible price.

Even in the United States, for a long time Jews were afraid. During World War II many Jewish leaders were reluctant to challenge the government’s indifference to the massacres in Europe for fear of stoking antisemitism here at home.

With the founding of the state of Israel, Jews finally took their masks off. This is who we are, we declared to the world, a free people who can practice our own tradition. Part of the rise of antisemitism today is the resentment of those who are angry at unmasked Jews. But we have worn masks long enough. This Purim we will put on temporary, celebratory masks but as the holiday ends, we will take them off – because the Jewish people need never wear masks again.

At the very end of the book of Exodus we read that a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night led the Israelites “in all their encampments.” The word for “encampments” is Masa, which refers to travel as well. Rashi, the great medieval commentator, says that an encampment is also a journey. In that profound observation we learn something about Jewish history and about life.

Jewish history demonstrates that every stop along the way before the land of Israel is temporary. Since the destruction of the Temple and the exile thousands of years ago, Jews have prayed for rain according to the season in Israel, not in the lands of their residence. We would ourselves toward Jerusalem in prayer, and dream of the return to Zion. Rashi, in France in the 11th century, understood that the Jewish encampment was one step along the journey, whose culmination would be a return to the land.

The second message is that we stop in order to renew our efforts, not to cease from striving. This past week at the #NeverIsNow conference, we saw people gather in one place to talk about the work of the ADL in combatting hate and building bridges. But the conference was not an end in itself. It was an encampment, a stop on the journey. From the meetings and discussions people gathered hizzuk, encouragement and strength, in order to renew the efforts to combat hate in our world. We all left stronger, more resolute and more able to face the challenges ahead.

In Pekuday we see that the Israelites need to pause in their journey across the wilderness to gather their strength. But they know they are heading somewhere; that each rest is also a renewal for the path ahead. Along with the ancient Israelites, we too travel in the wilderness. For us as well, our tradition and our vision serve as a fire by night that allow us to see the way forward. So together, as pilgrims of the soul have always done, we journey toward a better world in which antisemitism and other forms of hate will be a memory, and in Israel and around the world humanity will live in peace.

In our parasha for the very first time, Moses calls the people together. He does not do so in the face of Amalek or another enemy. War is not Moses’s method of unity. Rather he calls upon all of Israel and starts to tell them of Shabbat and of donating to the Tabernacle.

The ideal of gathering in Judaism is to do it for joy – to celebrate, to worship or simply to feel the glow of another’s presence. But over the centuries Jews have also gathered for solidarity. In an often hostile world, rather than dissipating and leaving one another alone, we have found strength in coming together both with other Jews and friends of goodwill who stand beside us.

This week at ADL’s major conference, “Never Is Now,” we have seen thousands of hopeful, resolute and passionate Jews and non-Jews join one another in New York to insist on the vitality of our tradition and the resolution to fight hate.

Here we brought together speakers from across the range of cultural and political trends in the U.S. We opened ourselves to listen and to engage. We were here to sharpen our skills in the unending practice of confronting antisemitism and other forms of hate that plague our society. By being present we pledged to be both witnesses and catalysts for change.

In Vayakhel, the Israelites build the Tabernacle. The Torah highlights Bezalel, the artist whose skill was essential to the sacred task. It reminds us that creativity, artistry and care must be taken in the great tasks of life. The way we design our discussions with one another should be a product of creativity as well as kindness.

As Vayakhel reminds us, we have gathered since ancient times – conferences are nothing new on the Jewish calendar! All of us need to feel our community, our closeness, our common cause – to move forward together. It was not easy in the time of Moses and it has not grown easier in our own day. But we are still responsible for one another, and we still have to hold hands on our way through the wilderness.

Coming down from Sinai with the carved tablets from God, we can understand Moses’s anguish at witnessing the Israelites worship the golden calf. Still, it is hard to understand why Moses then takes the tablets and smashes them on the ground.

One explanation among many offered, is that it was pure rage. Once he saw the Israelites dancing about an idol, Moses could no longer contain himself.

But this seems inadequate. Would Moses really allow anger alone to lead him to destroy the work of God, the most valuable single item in the history of the world? Was he that incapable of self-control? Better to have marched back up the mountain to deposit the tablets somewhere safe.

Arnold Ehrlich, author of Mikra Kipshuto, has a provocative and interesting answer. He notes that the Rabbis relate that God said to Moses: “Yishar kohacha (i.e., good for you!) that you broke them!” (Shabbat 87a). God apparently approved of Moses’s action. This signals that more than anger was at stake.

Ehrlich believes that Moses saw the calf and thought: If the Israelites worship this calf, which they created with their own hands, what will they do when they see the tablets carved by God? Surely, they will turn these tablets, which are so much more precious than the calf, into an idol! If I don’t destroy the tablets, they will commit the ultimate desecration.

By smashing the tablets, Moses was making a declaration to all of Israel: Even the handiwork of God, which you might think of as inviolable, is nonetheless just another material object. It is not a God – it is a physical artifact. I am destroying it to return you to the greater truth, which is that you were not delivered from Egypt by a thing, but by an intangible, unfathomable God, no more embodied in the tablets than in the calf.

We live in a world that venerates the accumulation of things. Idolatry is a persistent temptation – to worship at the shrine of stuff. Moses is reminding us that the ultimate reality, the greatest reality, is not material. Even in God’s world that which we most value – goodness, justice, love – are intangibles. We feel them, we enact them but they are not material. Like the tablets of the covenant, long after the item has crumbled to dust, the meaning, and the Creator, endure.

Prophets are dramatic. Everyone loves a prophet (so long as the prophet is not angry at them). The prophetic voice is rich with indignation, laced with scorn and elevated by righteousness.

By contrast, no one loves a bureaucrat. The person who files papers, insists on the correct manner of filling out forms, the one who draws lines and limits – it seems to bespeak a timidity of soul. Prophets are lone figures thundering from mountaintops. Bureaucrats are paper pushers who write bullet-pointed emails from the office.

Of course this is a caricature. This week, however, we turn in the Torah from the world of Moses to the world of Aaron, from the prophet to the Priest. And the Priest may be said to be, with some exaggeration, a kind of sacred bureaucrat. The Priest was there to follow procedures, to do things correctly, to maintain the institution of the tabernacle and the Temple.

In our world we see that institutions are not valued as they once were. From the courts to the universities to the halls of congress, people distrust the institutions that for so long stood as pillars of American life. For Jews, the synagogue was the central institution of Jewish life, but that too has come under pressure in an anti-institutional age.

Yet the Torah reminds us that institutions are critical to the health and survival of a community. They take time and care to build and are all too easy to destroy. Everything from the clothing of the Priest to the exact procedures matter; they are not trivial details but essential accoutrements of a properly functioning system.

We don’t note often enough that sacred work happens in synagogue committees. Over the coffee and stale bagels congregants and lay leaders in all sorts of organizations are doing something holy, but the day-to-day arrangements are essential to seed the ground for spiritual growth. In a beautiful parable, our sages speak of two men carrying large stones. An observer asks them what they are doing. “I’m carrying a heavy stone” says the first. The second answers, “I’m building the Temple of Solomon.”

Earlier, I commented glibly about no one loving a bureaucrat. Yet Aaron was dearly loved by the people, and not only because he was a pursuer of peace. I believe Israel understood that institutions are essential and those who care for them are shepherds of our welfare.

A rabbi once told me of teaching young children about the Jewish idea of God. He told them that God was everywhere. One boy reached out his hands, clapped them together and said, “Got Him!”

We are spatially oriented creatures. Although love, justice, mathematics and other accompaniments of life exist apart from physicality, God remains difficult to separate in our thoughts from notions of place. The rabbis explain that God is indeed called makom (place) because God is the place of the world, although the world is not God’s place. In other words, God encompasses this world but is also greater than it. Yet in our thoughts we locate God spatially, imagining God dwelling in the heavens or being more present in synagogues than in sewers.

Terumah, with its detailed creation of the mishkan, the tabernacle, reminds us that human beings need sacred space. “Make me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them (Exodus 25:8).” God dwells not in the sanctuary but among the people. You will feel God’s presence if there is a space to do so.

We realize, at least intellectually, that God is not in fact ‘more present’ inside the sanctuary than out on the street. The building of the mishkan did not entice the divine presence to dwell where it would otherwise be absent. Rather, the human demonstration of devotion evokes God’s spirit. God’s presence awaits our willingness. God is, as the Kotzker Rebbe famously said, wherever we let God in.

With all its specifications, the mishkan is intended to produce an effect on human beings, not on God. There is a beautiful story told of the great Seer of Lublin when he was a boy. He used to visit the forest and when his father asked him why, the boy explained, “I go there to find God.” When his father smiled and said, “but my child, don’t you know that God is the same everywhere?” the future hassidic master answered, “God is, but I’m not.”

The building of the mishkan did not change God, but it changed Israel. It taught us to both seek out and create spaces where we can feel God’s presence. God may be the same everywhere, but we are not.

The Torah reads “Six days shall you do your work, but on the seventh day you shall cease from labor” (Ex 23:12). But last week we read, “Remember the seventh day and keep it holy. Six days shall you labor and do all your work…” (Ex 20:8-9).

Why is the Sabbath mentioned first in one and last in another verse? The Izbitzer Rebbe, the Mei Hashiloah interprets this difference referring to the Gemara that asks: what happens if one is in the desert and has lost track of time and does not know when to observe Shabbat? (Shabbat 69b):

One Rabbi says to count six days from the day one loses track of time. Another says observe Shabbat first and then the following six days. What is the difference?

For some people, says the Mei Hashiloah, it is required that you do the work before you can get to Shabbat. First, the six days: In other words, you must cultivate good habits before you can consummate the week with holiness.

But, he says, there are times when you have a sudden, remarkable moment, when “Shabbat comes first,” and one can do something sacred and powerful without preparation.

The great violinist Isaac Stern was once approached by a fan after a concert who said, “Mr. Stern, I would do anything to play like you.”

“Really?” answered the virtuoso. “Would you practice 10 hours a day for 20 years? Because that’s what I did.”

That is usually the way – constant, intense effort. But there are blessed moments: Esther risks her life and saves the Jewish people. An obscure shepherd named David is anointed King. The Talmud teaches that some earn eternal life through many years of effort and others in an instant (Avoda Zara 18a).

Last week we read about the ineffable moment of Sinai. This week, Mishpatim, is about the daily rules, the effort, the rungs on the ladder to a good life. Much accomplishment is due to daily effort, but we also cherish instants of inspiration when the apple falls, the penny drops, and our vision shifts. If we are blessed we will merit both.

Psychologically we are predisposed to pay close attention to beginnings and endings.

Origin stories are seen as the keys to people’s lives. And psychological research has often shown that how something ends – whether an ordeal or a joyous occasion – has a greater impact than other features of the experience.

What begins and concludes the most significant event in the history of Israel?

God begins the Ten Commandments with “Anochi,” “I am.” There is a discussion among the commentators as to whether this constitutes a declaration or a commandment. Abarbanel, the great Spanish sage, declares that it is a preamble, making clear to the Israelites Who was speaking to them. Rambam, however, insists that it is a commandment, a mitzvah, the mitzvah of belief in one God.

The Israelites had seen God’s wonders enacted in Egypt, but they had not “met” God. Now the voice comes from the sky and creates the frame for everything that will follow. The “I” of God is the opening of the Ten Commandments.

How does the revelation conclude? The last commandment concerns coveting. The final words are “that belong to your neighbor.” Therefore, the first word is “I am,” and the final word is “neighbor.”

The motion from God to neighbor is the movement from the greatest generality to the most particular specific – like a movie shot that opens far above the earth and lands in someone’s kitchen. We thought we were dwelling in the empyrean only to find ourselves at the dinner table.

These laws are woven into the fabric of the universe. They are the will of the Creator, not the arbitrary decision of a jurist or the law of social cohesion. You can violate them, but you cannot change them.

Socially observed standards do change, sometimes radically, in the course of history. We abhor things today – slavery, child labor – that were once considered normative. Some therefore conclude, mistakenly, that there is no standard. There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so,” as Hamlet forlornly declares. The revelation at Sinai makes clear: there is a right and a wrong.

How we treat each other matters, and not only to one another, but also to the One who created us, for we are all children of God.

There is an old joke about a rich man who dies and stands before God. God asks, “I made you so wealthy, why did you give nothing to charity?” The man answers, “I will, I have many assets on earth, just let me give now!” The response from God thunders, “Up here, we only accept receipts.”