Source: X

Disturbing memes and images created using Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) are polluting social media with camouflaged hate and extremist propaganda.

Innovations in AI technology, plus a wider range of tools available than ever before, have enabled the use of AI image generators for nefarious purposes—some of which have been coordinated and crowdsourced online. In the last year, one GAI feature has emerged as a favorite among extremists: The ability to embed shapes, symbols and phrases into an otherwise innocuous image.

In certain GAI models, users can set additional conditions for a text-to-image output, allowing an image of one thing (say, clouds in the sky) to simultaneously show a different, unrelated shape within it (a bicycle, for example). The embedded content is typically best seen from a distance, or when the main image is shrunk down.

In innocuous cases, this technology can hide simple shapes like checkerboards, spirals or even QR codes. However, these techniques have been weaponized by extremists and antisemitic influencers to hide hate speech, hate symbols, antisemitic memes and even calls for violence.

Hate symbols and memes

For the last year, extremists and purveyors of hateful rhetoric have been sharing GAI propaganda with their networks online. On Telegram, a member of the antisemitic hate network Goyim Defense League (GDL) shared a GAI scene of a winter cabin with an embedded “Totenkopf,” a hate symbol used often by white supremacists.

Embedded Totenkopf in winter cabin, shared by GDL member. Source: Telegram

GhostEzra, a former QAnon adherent who now promotes antisemitic and neo-Nazi beliefs, shared a GAI image on Gab that shows several white women posing together in a field. The image also included an embedded Sonnenrad, a symbol that is often adopted by white supremacists and neo-Nazis.

Embedded Sonnenrad shared by antisemitic influencer Ghost Ezra. Source: Gab

These tools aren’t just used to share hate symbols—they’re also used to spread false narratives and conspiracy theories.

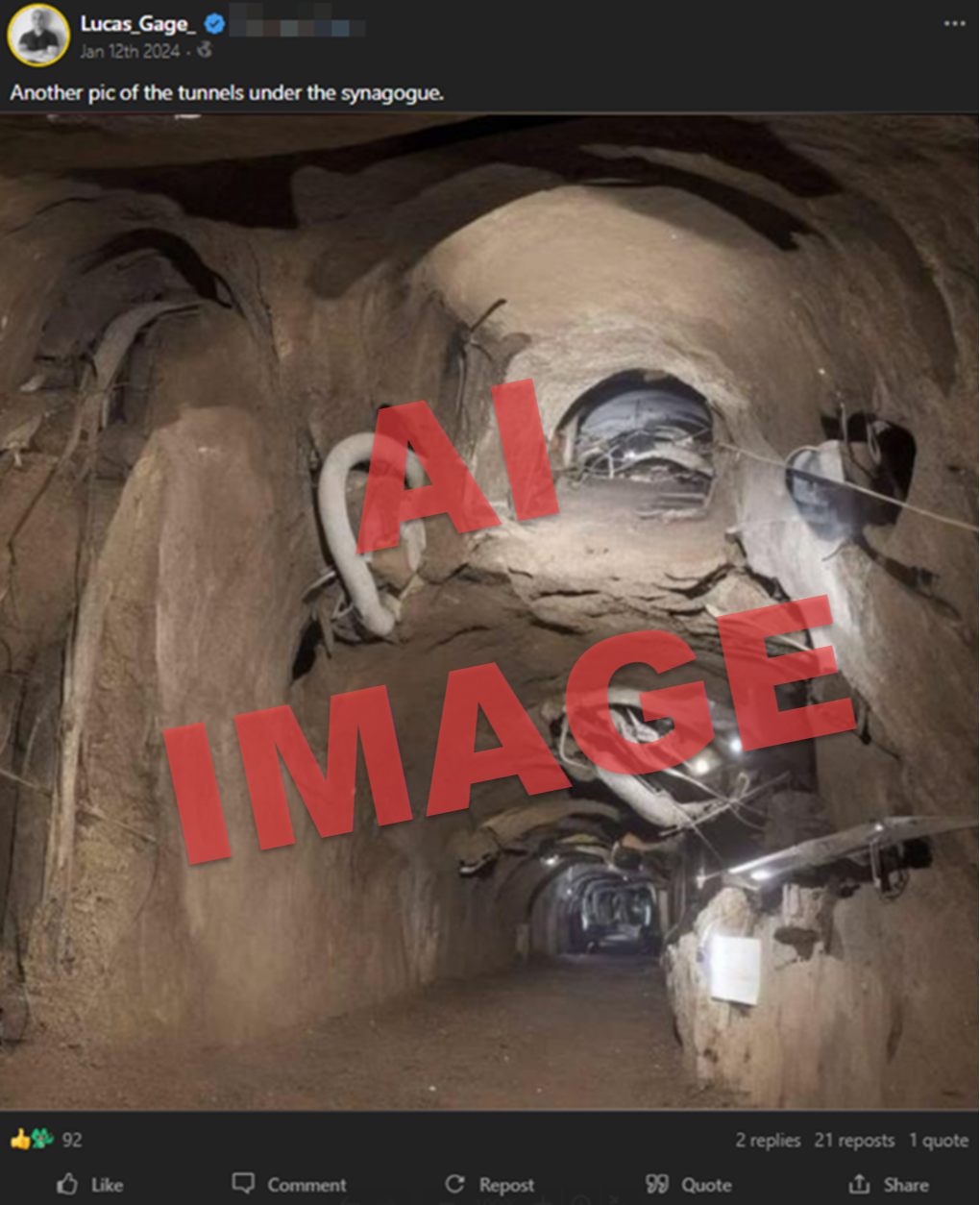

On Gab, antisemitic influencer Lucas Gage shared a GAI image of a tunnel, which also showed an antisemitic meme known as the Happy Merchant. Gage was referencing the January 2024 discovery of passageway found beneath Chabad headquarters in Brooklyn, New York, which led to a surge in antisemitic rhetoric and conspiracy theories online.

Happy Merchant meme in tunnel, posted by antisemitic influencer Lucas Gage. Source: Gab

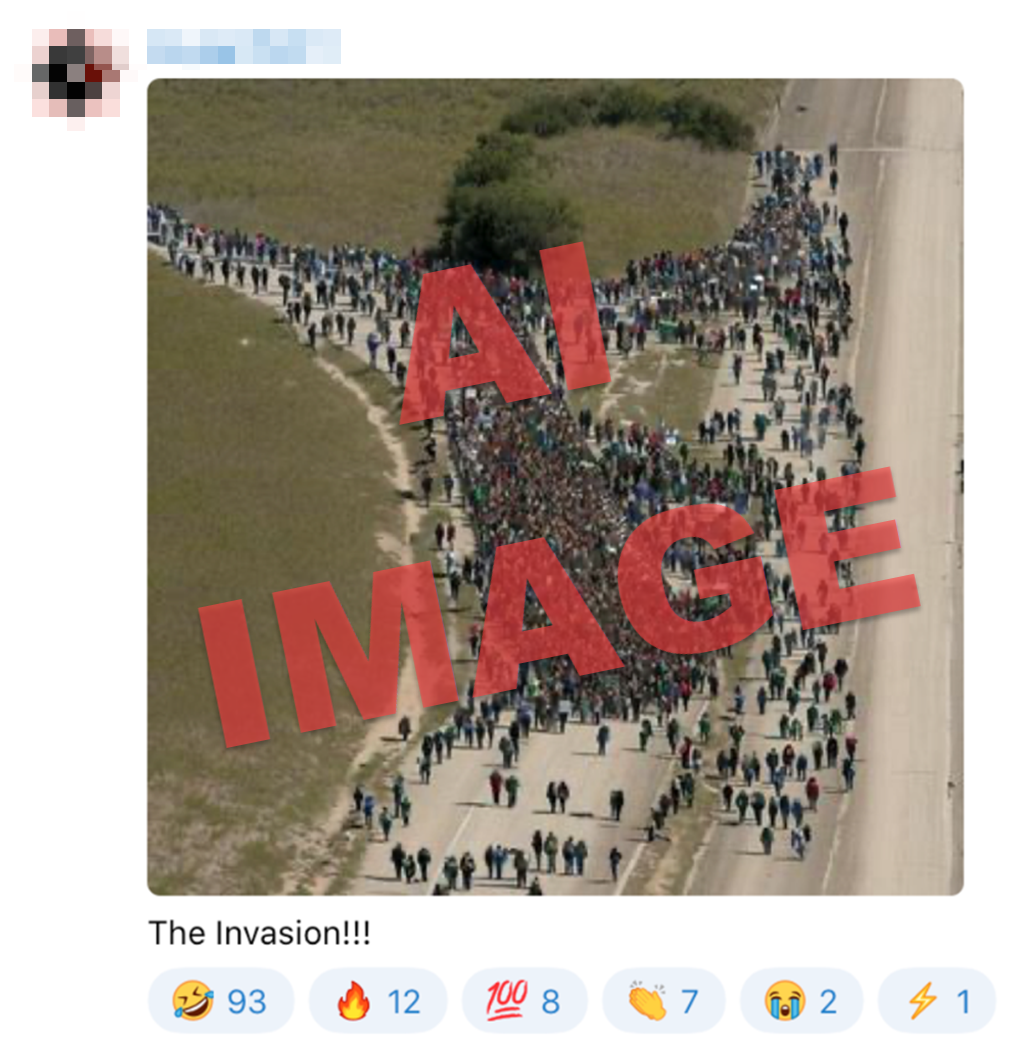

A Telegram channel affiliated with GDL shared a GAI image which shows a large group of people walking along a highway, as well as the Happy Merchant meme. The image caption references an “invasion,” presumably referring to migrants entering the U.S.

Happy Merchant meme in GAI depiction of migrant “invasion” in GDL chat. Source: Telegram

On X, antisemitic conspiracy theorist Stew Peters shared a different version of the same concept—this time showing the Happy Merchant meme in a GAI image of people crossing a body of water. In the post, Peters asks, “The invasion at our southern border is getting out of hand. Who is behind this madness?”

Happy Merchant meme disguised as “migrants,” shared by antisemitic far-right conspiracy theorist Stew Peters. Source: X

By combining antisemitism and xenophobic content, these individuals are promoting an antisemitic variation of the “Great Replacement” theory—a conspiratorial white supremacist narrative which claims that Jews are bringing non-white immigrants into to the U.S. to replace white people.

Calls for violence

In many cases, GAI image tools are used to hide violent rhetoric in seemingly benign content. One image, shared in the earlier days of the Israel-Hamas war, calls for the destruction of Israel.

The words "NUKE ISRAEL" in a GAI image of a patriot American family. Source: Telegram

Some images are xenophobic in nature, calling for the mass deportation of immigrants.

Embedded phrase “DEPORT THEM ALL” in image of people crossing body of water. Source: TikTok

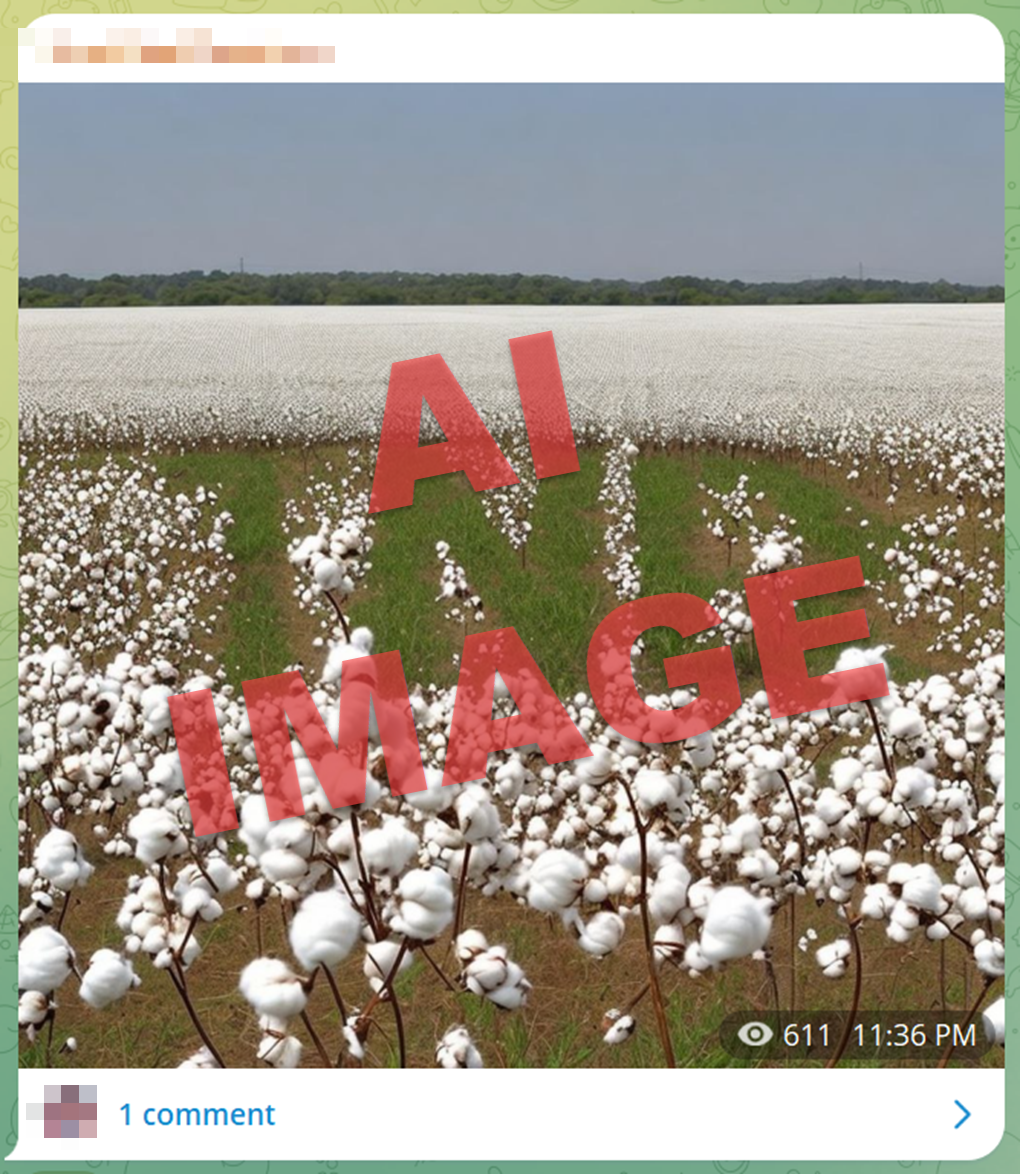

Others are explicitly violent, hiding acronyms like “TND”—a white supremacist shorthand for “total n***** death”—in a cotton field, an obvious allusion to slavery.

Embedded acronym “TND,” a white supremacist dog whistle, in a cotton field. Source: Telegram

Some images show general calls for the destruction of institutions, such as masonic lodges. Freemasons are a common talking point among conspiracy theorists, who believe freemasonry is linked to devil worship and a purported “New World Order.”

Embedded phrase, “BURN YOUR LOCAL MASONIC LODGE” in a carnival scene. Source: 4chan

Encouragement and coordination

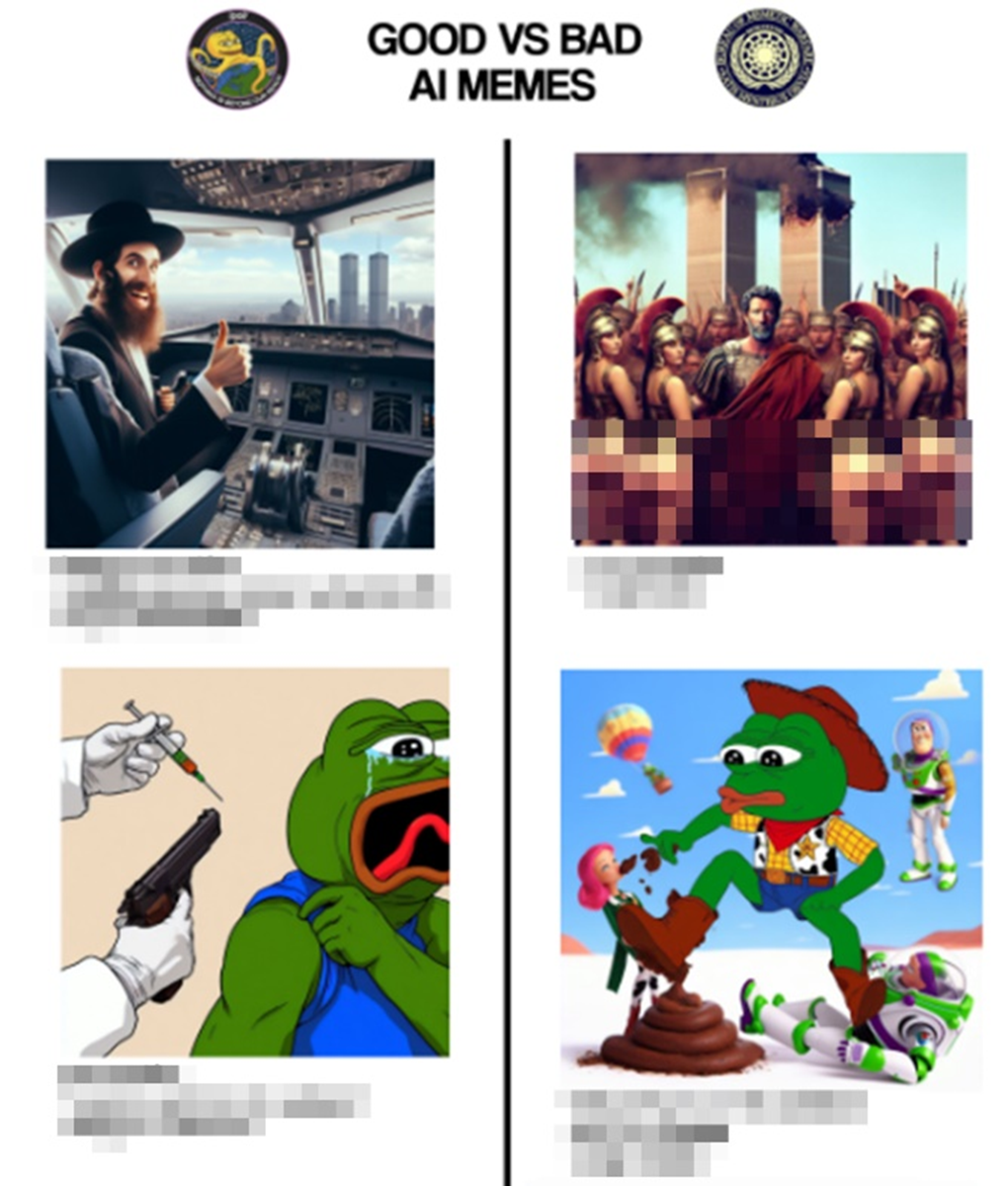

Around September 2023, users started creating threads on 4chan to encourage the use of GAI for what they call “memetic warfare,” advising users to create "propaganda for fun."

These posts include detailed guides, instructions and links on how to create the most effective GAI memes for “red pilling” (or radicalizing) the masses. Participants typically share their GAI images in the replies, resulting in dozens of new crowdsourced memes per thread. Guides also include tips on how to hide radicalizing or offensive content “in plain sight” using specific tools and workarounds.

One of several guides on how to create effective meme propaganda. Source: 4chan

Not all GAI memes can be attributed to the 4chan campaign. Similar images appear on a range of platforms including X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, TikTok and Telegram. Some of these spaces have accounts and channels dedicated solely to the creation of new and hateful GAI images.

Offline use

In early 2024, extremists began using hate symbol-embedded GAI images in their offline propaganda. While not yet widespread, this practice has the potential to become a concerning “real world” trend.

On April 20, 2024, the Michigan chapter of the white supremacist group White Lives Matter (WLM) rented three roadside billboards in the metro Detroit area. The displays depicted white supremacist dog whistles and commemorated Adolf Hitler’s birthday—a day often celebrated by white supremacist groups. One of the billboards included what appears to be a GAI rendering of a mountain range with an embedded image of Hitler.

One of three roadside billboards rented by WLM Michigan and showing a GAI image of Hitler. Source: X

The billboards were purchased through Billboard4Me.com. The company apologized in a public statement, explaining that the messages were “discreet enough to make it past the company’s filters” and noting WLM’s use of “deceptive imagery.”

Challenges and recommendations

GAI propaganda images differ from other forms of hateful imagery or memes in three key ways: Speed, scale and skill. Speed, because they are far quicker to generate than other images, scale, because they can be crowdsourced from users around the world and skill, because they require virtually no artistic training or design expertise to make.

In general, mitigating harmful GAI content comes with a unique set of challenges. Open-source GAI models allow users to essentially build their own chatbots or image generators, making such systems harder to regulate than those created with closed-source models. Also, by hiding calls for violence in these images, extremists are better able to evade content moderation on social media, because embedded text in an image is traditionally more difficult to detect than actual text in a post. This also means that more direct, targeted threats may go unnoticed, and therefore uninterrupted.

With this, social media platforms must invest in robust GAI policies and moderation to prevent such images from being posted. As it currently stands, these images are likely in a liminal space where they are technically in violation of hate policies, but an explicit rule which specifically prohibits hateful GAI content might not exist yet. Companies with proprietary AI models (such as OpenAi and Google) should also invest in technology which prevents the abuse of their tools for nefarious purposes.

These companies should also work with experts in terrorism and extremism, such as the ADL Center on Extremism, to model the potential threats posed by extremist abuse of their products. Companies that provide open-source models should create robust auditing methods to ensure that the AI models they are hosting are not explicitly trained to spread hate and amplify extremist ideologies.