Related Content

Fight Antisemitism

Explore resources and ADL's impact on the National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism.

Introduction

In late 2022, NORC and ADL surveyed a nationally representative sample of over 4,000 Americans to better understand attitudes toward Jews and Israel. The survey included several batteries of questions, including: sections probing general attitudes toward Jews and Israel; questions designed to understand respondents’ level of agreement with both historic and contemporary anti-Jewish and anti-Israel tropes; questions measuring literacy and familiarity with Jews and Israel; several comparative prejudice experiments; and general conspiracy theory belief questions.

As detailed in an earlier topline report, the research revealed widespread levels of anti-Jewish sentiment among American adults. ADL found that a significant proportion of Americans saw Jews as:

- Clannish outsiders: 70 percent and 53 percent of Americans said that Jews stick together more than others and go out of their way to hire other Jews, respectively

- Dually loyal: 39 percent of Americans thought Jews are more loyal to Israel than to the United States

- Disproportionately powerful: 38 percent of Americans thought Jews always like to be at the head of things, 26 percent thought Jews have too much power in business, and 20 percent thought Jews have too much power in the United States today

On average, Americans agreed with 4.2 of the 14 statements included in the anti-Jewish question

The research also demonstrated that negative sentiments toward Israel, including anti-Israel sentiments rooted in antisemitic conspiracy theories, were held by broad swaths of the American

- Almost half (40 percent) of Americans agreed that Israel treats the Palestinians like the Nazis treated the Jews

- About a quarter (24 percent) of Americans thought that Israel does not make a positive contribution to the world, and that Israel and its supporters are a bad influence on our democracy

- Just under a fifth (18 percent) of Americans said they were not comfortable spending time with people who support Israel

Given these findings, researchers further probed where such attitudes and sentiments were coming from, what phenomena did they overlap with, and how did they manifest. If people agreed with more antisemitic tropes or had negative views on Israel, what else did they think, feel, or know about Jews or Israel?

As will be outlined below, researchers found several overarching answers to that question. Generally speaking, respondents who agreed with more anti-Jewish tropes:

- Knew significantly less about Jews, Judaism, and Jewish history, including under-counting the number of Jews who died in the Holocaust and overestimating the proportional size of the American Jewish community

- Were somewhat more likely to not have any relationships with Jewish people and/or classify their past experiences with Jews more negatively

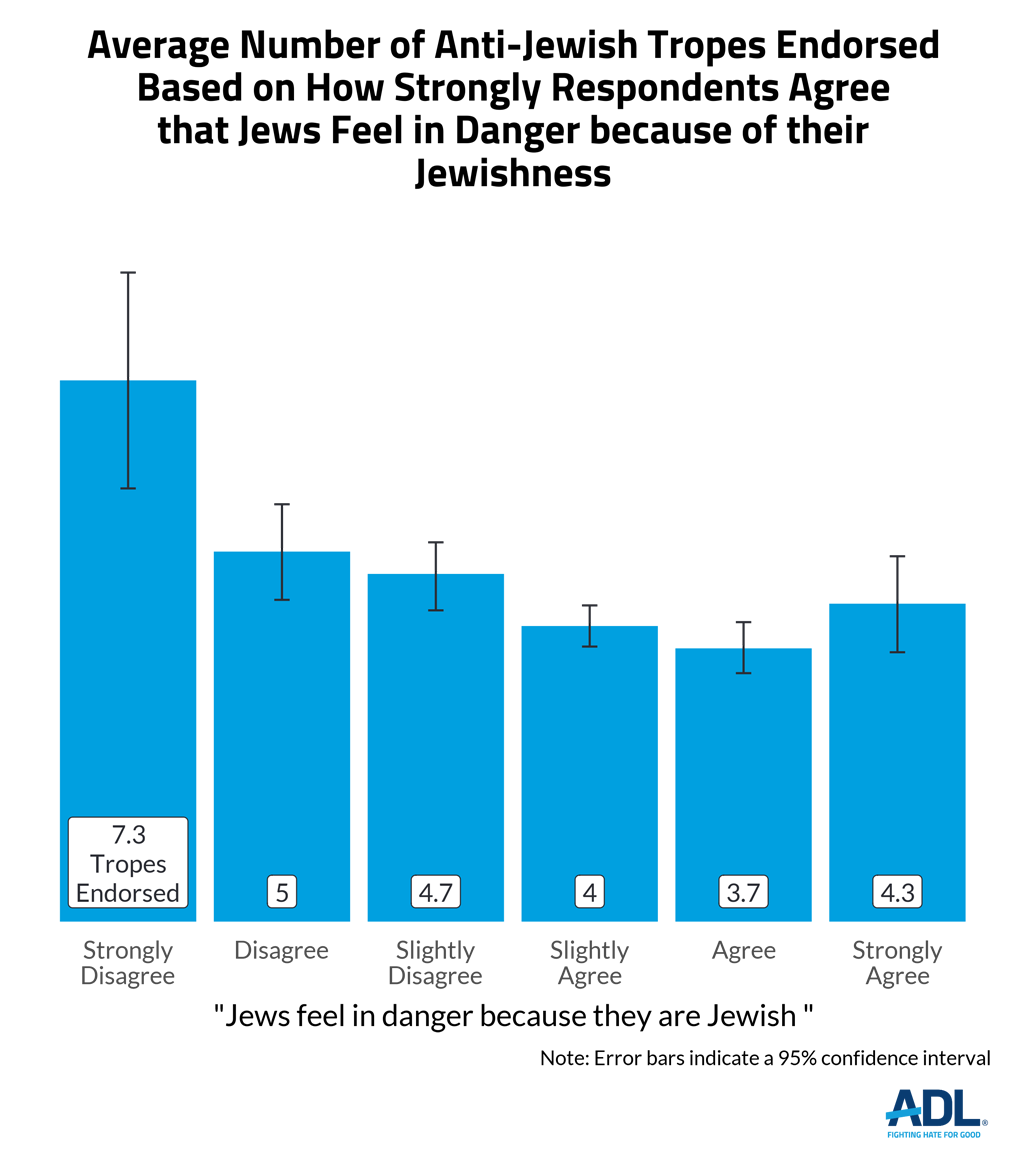

- Were significantly less likely to think that Jews face organized hostility or danger for being Jewish, or that Jew-hatred is a serious or growing problem

- Broadly, as one of the study’s experiments demonstrated, the term “Jew” has a Whitening effect on how people perceive individuals of ambiguous race. For White Americans, seeing a Jew as “White” (i.e., like them) was associated with believing fewer anti-Jewish tropes. For people of color, there was no significant relationship between perceiving Jews as White and anti-Jewish trope belief

- Were significantly more likely to believe a range of conspiracy theories, including a conspiracy theory question designed to resemble the Great Replacement Theory

In contrast, researchers found that few of these factors had statistically significant relationships with sentiment toward Israel. Indeed, only one factor, the extent to which a respondent had a negative experience with Jews, was associated with sentiment toward Israel and, even then, it did so marginally. In fact, respondents appear willing to condemn or condone Israel and its supporters largely independent of their level of knowledge about Israel.

Taken together, these findings help draw a new, composite portrait of how people feel about Jews and Israel. This portrait illuminates both key predictors of negative attitudes towards Jews and Israel and critical avenues for future causal research.

This report is the second in a multi-part series based on ADL’s 2022 study with the National Opinion Research Center in partnership with the One8 Foundation. Future reports, to be published in the coming months, will use additional data from the survey to explore how and why anti-Jewish and anti-Israel attitudes spread, as well as in which demographic subgroups antisemitic and anti-Israel sentiments are most common.

Is Knowledge About Jews, Judaism, and Jewish History Related to One’s Level of Anti-Jewish Attitudes?

To assess the relationship between knowledge and antisemitic beliefs, the study included several knowledge self-assessment and fact-based questions about Judaism, the American Jewish community, and the Holocaust.

Researchers first asked how much respondents thought they knew about Jews and Judaism. People who assessed their knowledge as being higher agreed with fewer anti-Jewish tropes than respondents who assessed their level of knowledge as being lower. Specifically, respondents who said that they knew “a great deal” or “some” about Jews and Judaism agreed with 3.8 anti-Jewish tropes, compared to 5.2 tropes among those who said they knew “nothing” about Jews and Judaism.

Researchers then asked respondents a series of fact-based questions to confirm what respondents actually knew about Jews and Jewish history.

One multiple-choice, fact-based question asked people what percent of the American population Jews comprise. Respondents who were able to correctly answer this question endorsed, on average, the least anti-Jewish tropes, while those who greatly overestimated the size of the American Jewish population agreed with the most anti-Jewish statements. Specifically, those who correctly answered 2 percent (the actual percent size of the American Jewish population) agreed with an average of 3.6 anti-Jewish tropes, while those who believed that Jews comprised 21 percent or more of the American population agreed with, on average, 6.4 anti-Jewish tropes.

Researchers compared respondents’ level of self-assessed knowledge about Jews and Judaism to whether they correctly answered the question about American Jewish population size. Interestingly, respondents who overestimated their knowledge of Jews and Judaism (i.e., they said they knew a great deal about Jews and Judaism but answered incorrectly when asked about the size of the Jewish population) agreed with 1.2 more anti-Jewish tropes than those who correctly estimated their knowledge (or lack

A second multiple-choice, fact-based question in the survey asked how many Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Respondents who correctly answered that 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust believed the fewest anti-Jewish tropes: 3.2, on average. In contrast, those who thought that less than one million Jews died in the Holocaust believed, on average, 7.3 tropes, while those who indicated they did not know the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust believed, on average, 5.3 anti-Jewish tropes.

Finally, researchers probed whether how one learned about the Holocaust was predictive of one’s belief in anti-Jewish tropes. Respondents who indicated their school taught specifically about the Holocaust endorsed the fewest anti-Jewish tropes (3.8, on average).

Is Personally Knowing Jews Related to One’s Level of Anti-Jewish Attitudes?

The study included several questions to understand respondents’ level of contact with Jews and the Jewish community, including questions pertaining to the size of one’s Jewish network and how they would describe their past experiences with Jews.

Researchers explored whether the size of one’s Jewish network was related to one’s level of anti-Jewish attitudes. The chart below shows the average number of anti-Jewish tropes believed by the number of Jews a respondent personally knows, with each bar representing approximately 25 percent of the American population.

While the chart below shows an overall decrease in anti-Jewish trope belief associated with the more Jews a respondent knows, the differences are only statistically significant at the two extremes. Put another way, people who don’t know any Jews were likely to agree with a greater number of anti-Jewish tropes than people who know 7+ Jews (5.0 vs. 3.6 anti-Jewish tropes, respectively). However, the differences in anti-Jewish attitudes among those who know 1-2 or 3-6 Jewish people are not statistically significant when compared to those who don’t know any Jews or those who know 7+ Jewish people.

Researchers then sought to understand the relationship between how people described their past experiences with Jews and their current levels of anti-Jewish attitudes. Encouragingly, most respondents in the study described their past experiences with Jews positively. It follows, though, that even respondents who described their past experiences with Jews as “very positive” or “positive” agreed with some anti-Jewish tropes (2.6 and 3.2, respectively). However, the fifth (21 percent) of respondents who described their past experiences with Jews as only “somewhat positive” or “negative” were significantly more likely to agree with a much greater number of anti-Jewish tropes (6.3 and 10.0, respectively).

Is Viewing Jews as White Related to One’s Level of Anti-Jewish Attitudes?

Figure 1 Picture Respondent's Viewed for In-Survey Experiment

Researchers included a number of experiments in the study, including one designed to assess how respondents racially categorize Jews.

Respondents were randomly assigned to three equally-sized groups; the first group was told the person pictured above was a Jewish singer from Israel, the second group was told the person pictured was an Arab singer from Iraq, and the third group was told that the person pictured was a singer from the United States.. All respondents were then asked if they would consider the person w

This experiment revealed that being considered Jewish has a ‘whitening effect.’ Respondents who were told that the photo was of a Jewish singer from Israel were much more likely to consider the person white than respondents who were told the person was an Arab singer from Iraq or a singer from the United States.

Researchers explored, using the 1,307 respondents who were told the singer was Jewish, whether there was a relationship between one’s racial categorization of Jews and one’s level of anti-Jewish attitudes. For white-identifying respondents, perceiving Jews as white was associated with believing 1.18 fewer anti-Jewish tropes, even while controlling for other demographic factors. The relationship between perceiving Jews as white and one’s level of anti-Jewish attitudes was not statistically significant for respondents who identified as people of color. Greater detail regarding how attitudes toward Jews and Israel differ between demographic subgroups will be shared in a forthcoming report.

Are Conspiratorial Beliefs Related to One’s Level of Anti-Jewish Attitudes?

Given that anti-Jewish tropes are often rooted in conspiratorial thinking related to disproportionate Jewish control or power, researchers sought to better understand the relationship between anti-Jewish sentiment and a general conspiratorial mindset. To that end, several questions were included in the survey aimed at understanding to what extent respondents believed that various events or populations in the world are affected by secret activities or forces.

Researchers found that people who believed in more anti-Jewish tropes also showed a disposition toward conspiratorial thinking. In general, as support for different conspiracy theories increased, so too did agreement with anti-Jewish tropes. For example, those who strongly agreed with the statement that “seemingly unconnected events are often the result of secret activities” agreed with 6.7 anti-Jewish tropes, compared to 2.5 anti-Jewish tropes among those who strongly disagreed with that statement. Similarly, those who strongly agreed with the statement that “there are secret organizations that greatly influence political decisions” agreed with 5.2 anti-Jewish tropes, compared to 2.7 anti-Jewish tropes among those who strongly disagreed with the statement.

One of the conspiratorial beliefs included in the survey was designed to resemble the Great Replacement

What is Related to Negative Perceptions of Israel?

As referenced in the Introduction, ADL’s 2022 research revealed that negative sentiments toward Israel, including anti-Israel attitudes rooted in anti-Jewish conspiracy theories, were held by broad swaths of the American population:

- Almost half (40 percent) of Americans agreed that Israel treats the Palestinians like the Nazis treated the Jews

- About a quarter (24 percent) of Americans thought that Israel does not make a positive contribution to the world, and that Israel and its supporters are a bad influence on our (American) democracy

- Just under a fifth (18 percent) of Americans said they were not comfortable spending time with people who support Israel

Just as researchers sought to better understand which factors were linked to respondents agreeing with more anti-Jewish tropes (as described in sections 1-5 of this report), researchers also explored whether those drivers connected to respondents’ sentiments toward Israel. The analysis revealed that 3 of the 4 factors linked with respondents agreeing with more anti-Jewish tropes (knowledge, perceptions of Jew-hatred, and conspiratorial thinking) had little to no relationship with one’s sentiment toward Israel.

Researchers found no statistically significant relationship between correctly answering the fact-based questions in the survey (number of Jews killed in the Holocaust; perceived size of the American Jewish population) and sentiment toward Israel. Further, the relationship between the number of Jews one knows and one’s attitude toward Israel was not statistically significant. Researchers also found no statistically significant association between one’s sentiment toward Israel and respondents’ perceptions of Jew-hatred, whiteness, or level of conspiratorial thinking.

Paralleling the question asked regarding self-perceived knowledge about Jews and Judaism, researchers also asked respondents how much they thought they knew about Israel, its history, and the people who live there.

The statistical relationship between self-perceived knowledge about Israel and level of agreement with anti-Israel statements was weak, as one’s level of self-assessed knowledge about Israel and Israelis was statistically significant only on the extremes of the scale after demographic controls were taken into account. In other words, respondents felt able to condemn or condone Israel and its supporters regardless of how much they thought they knew about Israel. Indeed, almost 40% of respondents do not think Israel is a country in the Middle East, and, further, knowing that Israel is in the Middle East is not at all related to sentiment toward Israel.

Researchers did find that the more positive one’s past experiences with Jews, the more comfortable they were spending time with supporters of Israel, and the more they thought Israel makes a positive contribution to the world. In general, though, the relationship between the different sentiments about Israel included in the study and the positivity of past experiences with Jews was not particularly

Overall, people’s views on Israel appear less dependent on their personal experience and knowledge of Israel or Jews. Instead, views of Israel appear to depend more on several demographic variables, including one’s age, political orientation, and racial/ethnic background. Future reports will further explore which demographic subgroups harbor more or less antisemitic and anti-Israel sentiments.

Conclusion

Researchers explored a variety of topics to better understand which factors are linked with holding greater numbers of anti-Jewish and anti-Israel attitudes. Overall, the study revealed that people who believe a higher number of anti-Jewish tropes tend to: 1) know little about Jews, Judaism, and Jewish history; 2) not have any relationships with Jewish people and/or describe their past experiences with Jews negatively; 3) not think that Jews face hostility or danger in the United States today; and 4) show a general disposition toward conspiracy theory thinking. Researchers also found that being told someone is Jewish (and from Israel) increases the likelihood of perceiving that person as racially White. Understanding the relative predictive power of each of these variables will have significant implications in developing strategies aimed at ameliorating antisemitism.

In contrast, there was a weak statistical relationship between these variables and one’s level of anti-Israel attitudes. In fact, people’s attitudes towards Israel and Israelis seem to be shaped largely independently of one’s level of knowledge or relationships, with the important exception that the negative experience does appear to somewhat affect agreement with a few negative sentiments toward Israel. This finding raises important questions around how best to address anti-Israel sentiments.

Forthcoming reports will use additional data from ADL’s 2022 research study to explore how and why anti-Jewish and anti-Israel attitudes spread, as well as in which demographic subgroups anti-Jewish and anti-Israel sentiments are most common.

Appendix

Sample

The sample contains 4,007 respondents from the National Opinion Research Center’s AmeriSpeak panel surveyed from September through October of 2022. Since its founding by NORC at the University of Chicago in 2015, AmeriSpeak has produced more than 900 surveys, been cited by dozens of media outlets and become the primary survey partner of the nation's preeminent news service, The Associated Press. AmeriSpeak was chosen for this study because of its scientifically rigorous panel and its strong representation of hard-to-reach populations, including low-income households, less educated persons, young adults, rural households, persons who are less interested in the news, and social and political conservatives.

Indeed, careful attention was paid to ensure the probability sample included a broad swath of respondents from a range of socio-economic, political and ethno-racial backgrounds. This is a weighted, representative sample of Americans generally, and of the sub-populations that researchers oversampled: those between the ages of 18 and 30 (1,292 respondents), those on the political Right (420) and political Left (663), Black Americans (578) and Hispanic Americans (626). 15,862 respondents of the AmeriSpeak panel were invited to take this survey, of which 4,007 completed the instrument.

The study was registered with the University of Chicago’s Institutional Review Board for the Ethical Treatment of Human Subjects. The data are weighted to represent the general population of the United States in addition to the aforementioned subpopulations using the benchmarks of the demographic profile of the National Opinion Research Center’s AmeriSpeak panel and its 2021 General Social Survey.

ADL and its partners seek to ensure the data and methodology are transparent and shared with the public. To that end, the data will be released through ICPSR at the University of Michigan.

Survey

The survey questionnaire was designed as a large-scale collaboration between the staff at the ADL Center for Antisemitism Research, NORC, the One8 Foundation, Jewish communal and civil rights leaders, and an academic advisory board of scholars. Wherever possible, researchers incorporated questions that had been asked and validated elsewhere (such as the statements related to Israel) or had been asked previously by ADL (such as the ADL Index of anti-Jewish tropes).

Decades-long studies, such as the ADL Index, must balance continuity around measures while updating methods to ensure greater rigor and modern practices. Researchers opted to use the same 11 classic statements that probe, in particular, authoritarian anti-Jewish conspiratorial belief. In addition, researchers added back in a predictive statement that, while asked in the original 1964 study, had been dropped more recently. Further, researchers added two positively phrased statements in order to ensure greater rigor in the presentation of the attitudinal battery.

In some cases, researchers made changes based on methodological best practice. For example, for the current survey, researchers opted to remove the “Unsure/Don’t Know” option for anti-Jewish tropes, considering it a crucial adjustment to the rigor of the study. While it is important to retain the “Unsure/Don’t Know” option for fact-based questions (some people just do not know a fact), for opinion-based questions, it is broadly better to compel some meaningful selection. Accordingly, the “Do not know” option was available for the fact-based questions about the size of the Jewish population in the US and the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust.

In addition to the historical measures of antisemitism, researchers added questions aimed at a contextual understanding of antisemitism vis-à-vis a broad worldview. Accordingly, researchers added questions about conspiracy theories not directly related to Jews, as well as questions on knowledge about Jews and Israel, perceptions of Jewish privilege and several experiments. Future reports will include analysis of the variables not addressed in this report.

Frequency Plots of Each Variable

Acknowledgements

The continued partnership of the One8 Foundation.

Research support provided by Graham Wright and Leonard Saxe of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University.