Related Resources:

Fight Antisemitism

Explore resources and ADL's impact on the National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism.

An analysis of how friends, family, religious institutions, talk radio, pop culture, politicians and social media predict anti-Jewish and anti-Israel attitudes.

Introduction

In late 2022, the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago (NORC) and ADL surveyed a nationally representative sample of over 4,000 Americans to better understand attitudes toward Jews and Israel. The survey included several batteries of questions, including sections probing general attitudes toward Jews and Israel; questions designed to understand respondents’ level of agreement with both historic and contemporary anti-Jewish and anti-Israel tropes; questions measuring literacy and familiarity with Jews and Israel; several comparative prejudice experiments; and general conspiracy theory belief questions.

This report is the third in a multi-part series using data from the 2022 study.

The first report was published in January 2023 and outlined topline findings, including:

- On average, Americans agreed with 4.2 of the 14 statements in the anti-Jewish question battery.

- 20% of Americans agreed with 6+ of the original 11 statements - the highest level of antisemitic attitudes detected in decades of asking this same series of questions.

- Negative sentiments toward Israel, including anti-Israel sentiments rooted in antisemitic conspiracy theories, were held by broad swaths of the American population; including 23% of respondents who at least slightly agreed that Israel can get away with anything because its supporters control the media and the 18% of respondents who did not feel comfortable spending time with people who openly support Israel.

The second report, published in March 2023, sought to answer the question: if people agreed with more antisemitic tropes or had more negative views on Israel, what else did they think, feel, or know about Jews or Israel? Researchers found that, respondents who agreed with more anti-Jewish tropes:

- Knew significantly less about Jews, Judaism, and Jewish history

- Were somewhat more likely to not have any relationships with Jewish people and/or classify their past experiences with Jews more negatively

- Were significantly less likely to think that Jews face organized hostility or danger for being Jewish, or that Jew-hatred is a serious or growing problem

- Were significantly more likely to believe a range of conspiracy theories, including a conspiracy theory question designed to resemble the Great Replacement Theory

- Additionally, respondents appeared to condemn or condone Israel and its supporters largely independent of their level of knowledge about Israel or relationships with Jews.

This third report focuses on the environments through which antisemitic and anti-Israel attitudes spread. More specifically, it aims to answer two broad questions:

- Where and how frequently are people exposed to antisemitic and anti-Israel rhetoric?

- Which exposures to antisemitic and anti-Israel rhetoric are most predictive of negative attitudes toward Jews and Israel?

Researchers identified two broad answers to these questions.

The majority of exposures to anti-Jewish and anti-Israel comments come from popular culture, politicians, and social media, with friends and family being the least likely sources of anti-Jewish or anti-Israel comments.

However, one’s friends and family appear to be the most significant predictors of one’s own beliefs about Jews and Israel. Broadly, being surrounded by people who dislike Jews or who make negative comments about Jews is a significant factor in one’s own attitudes about Jews and Israel.

A forthcoming, fourth report using data from ADL and NORC’s 2022 study will explore the typologies of different antisemitic beliefs and their prevalence among different groups in American society.

How are people exposed to anti-Jewish and anti-Israel comments?

Researchers assessed how respondents are exposed to anti-Jewish and anti-Israel comments by asking questions that probed how frequently respondents hear this rhetoric across a variety of political, cultural, religious, media, and social sources.

Encouragingly, for all the sources asked about, most respondents stated that they heard anti-Jewish comments either “never” or “rarely.” However, between about a fifth and a third of respondents reported hearing anti-Jewish comments either “often” or “sometimes” from the political, cultural, and media sources in the study (i.e., politicians, TV & movies, social media, news outlets, and talk radio/podcasts). Respondents reported hearing anti-Jewish comments less frequently from their social and religious surroundings, specifically family, friends, and religious organizations.

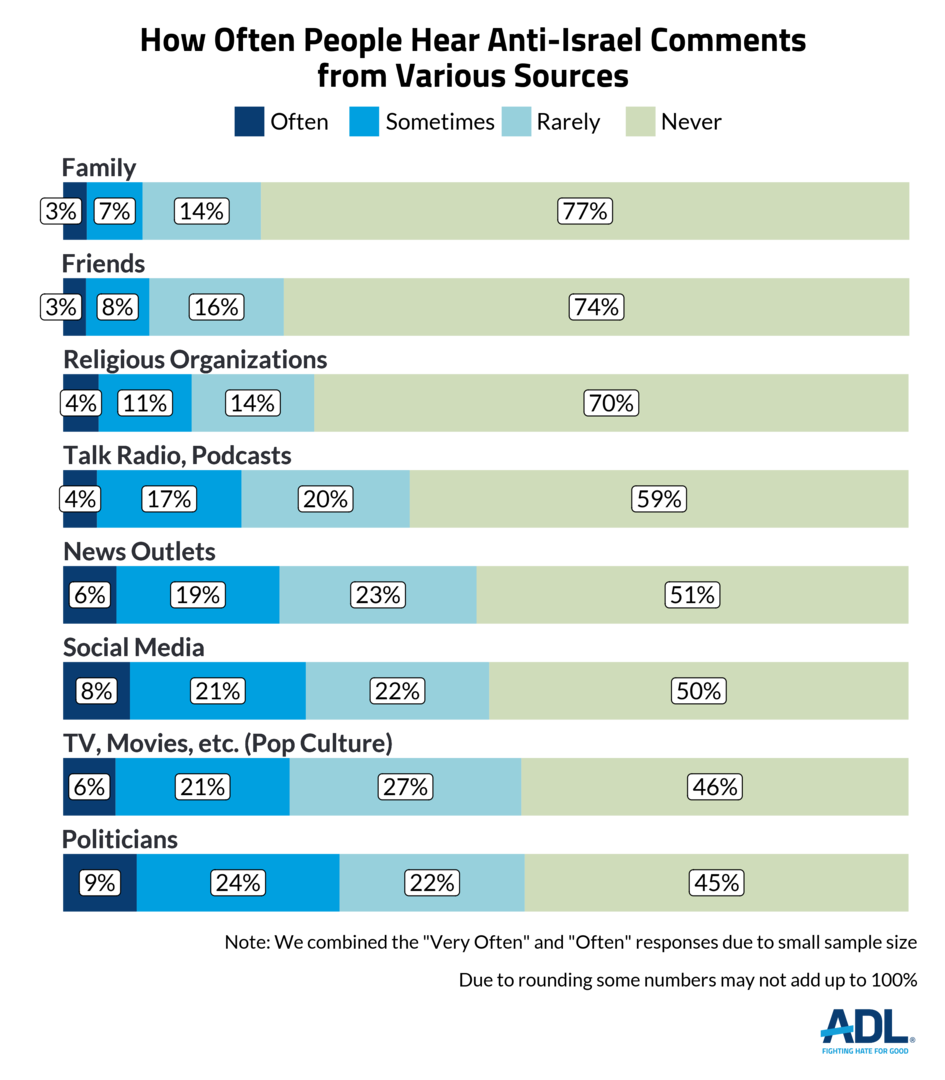

Respondents were also asked how often they hear anti-Israel rhetoric. As with anti-Jewish comments, political, cultural, and media sources were responsible for the bulk of one’s exposure to anti-Israel comments, though politicians surpassed TV/movies as the most frequent source. Between a fifth and a third of respondents reported hearing anti-Israel comments either “often” or “sometimes” from politicians, social media, TV & movies, news outlets, and talk radio/podcasts. Similarly, to anti-Jewish comments, respondents reported hearing anti-Israel comments less frequently from their family, friends, and religious organizations.

Which exposures are predictive of respondents’ anti-Jewish beliefs?

After assessing where and how frequently people were exposed to anti-Jewish comments, researchers then sought to quantify the relationship between these environmental inputs and one’s own beliefs. In other words, which exposures to antisemitic rhetoric were most predictive of negative attitudes toward Jews?

Researchers found that a respondent’s social network is predictive of the number of antisemitic tropes with which one agrees.

Although respondents said they heard anti-Jewish comments less frequently from their family and friends than from political, cultural and media sources, one’s social networks were stronger predictors of one’s beliefs. For every level increase in how frequently respondents heard anti-Jewish comments from friends and family, they endorsed 1.53 and 1.36 more anti-Jewish tropes, respectively (on average, Americans agreed with 4.2 of the 14 statements included in the anti-Jewish question battery). In other words, someone who reportedly hears anti-Jewish comments often from friends, endorses 1.53 more anti-Jewish tropes, on average, than someone who hears anti-Jewish comments from their friends only sometimes. In contrast, hearing anti-Jewish comments more frequently from talk radio/podcasts, news outlets, social media, politicians, and TV/movies had a weaker impact (between .25 and .59 more anti-Jewish tropes, on average).

The study also included several questions to quantify how many people respondents have in their in-person and online social networks who dislike and/or like Jews. Encouragingly, most respondents (70%) have at least one friend or family member that likes Jews, and only about a fifth (19%) of respondents have one or more friend or family member who dislikes Jews. A smaller, though still significant, proportion of respondents have at least one person in their online social network who dislikes Jews (12%).

Researchers found that the number of one’s friends and family who like or dislike Jews was strongly associated with one’s anti-Jewish attitudes. People who reported having more friends or family members who dislike Jews predicted, on average, significantly more anti-Jewish tropes. Respondents who reported having 0 friends or family members who dislike Jews believed on average 3.3 anti-Jewish tropes. In contrast, respondents who said that they had 1-5 friends or family members who dislike Jews believed on average 5.5 anti-Jewish tropes. The small percentage of respondents (9%) who said that they had 6 or more friends or family members who dislike Jews believed on average 6.8 anti-Jewish tropes. Researchers found similar associations with online social networks.

While the effect of surrounding oneself with people who like Jews was less pronounced than the effect of surrounding oneself with people who dislike Jews, it still had an impact. Compared to respondents with 0 friends or family members who like Jews, there is not a significant difference among those with 1-5 friends or family members. However, those with 6 or more friends or family members who like Jews endorsed significantly fewer anti-Jewish tropes, endorsing only 2.8 anti-Jewish tropes, on average.

Which exposures are predictive of respondents’ negative sentiment toward Israel?

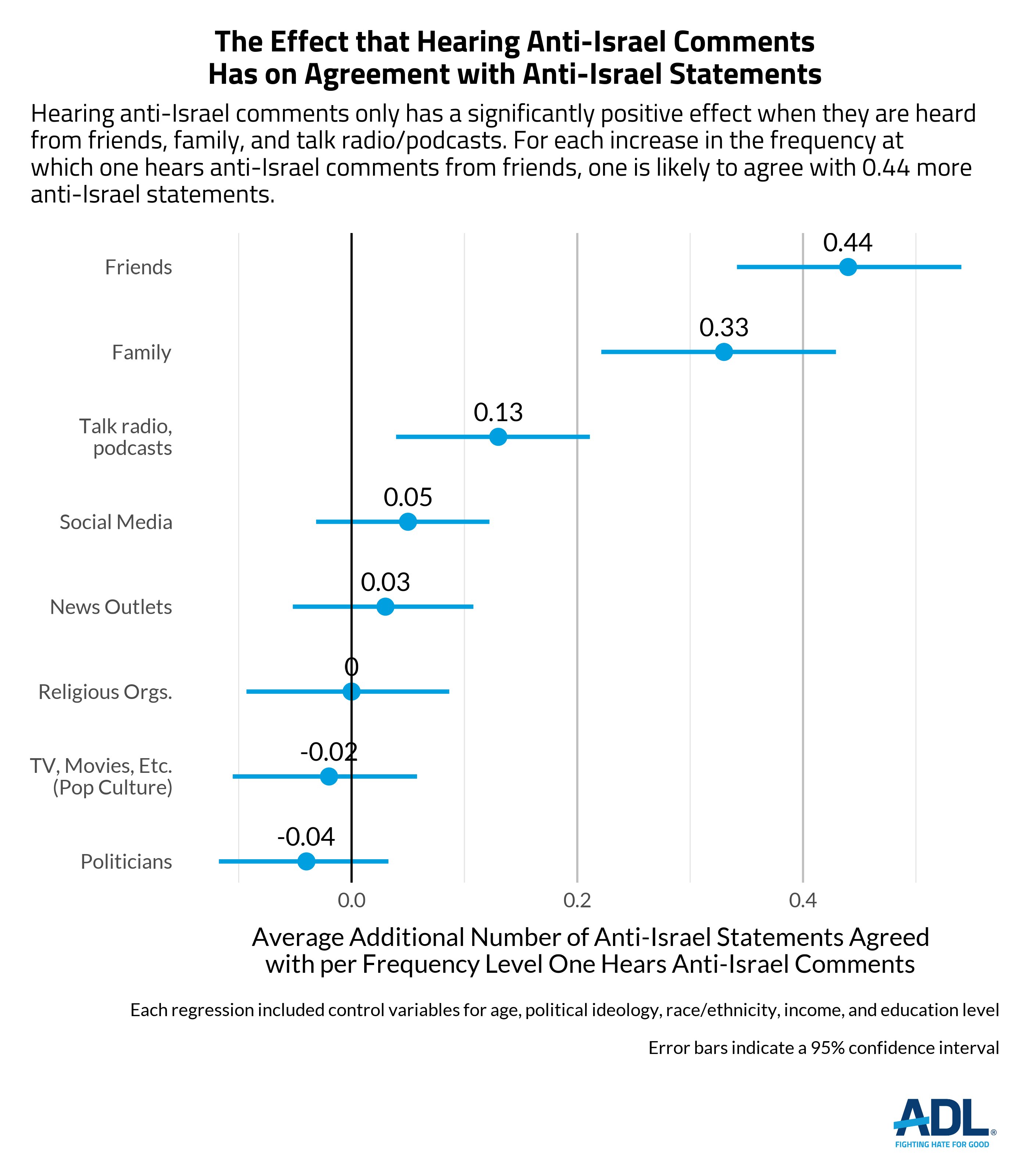

Parallel to the analysis described in Section 2, researchers also explored the relationship between respondents’ levels of negative sentiments toward Israel and their social surroundings. Again, researchers found that a respondent’s social network was a significant driver of one’s level of negative sentiments toward Israel. With that said, the relationship is weaker than for belief in anti-Jewish tropes.

For every increase in the level of frequency that respondents heard anti-Israel comments from friends or family, they carried .44 and .33 more negative sentiments toward Israel on average, respectively. In contrast, there was no statistically significant relationship with one’s negative sentiments toward Israel and how frequently one heard anti-Israel comments from most political, cultural, and media sources (i.e., TV/movies, news outlets, politicians, religious organizations, and/or social media). The one exception was that hearing anti-Israel comments from talk radio/podcasts had a very small (though statistically significant) relationship: each increase in frequency was associated with .13 negative sentiments toward Israel, on average.

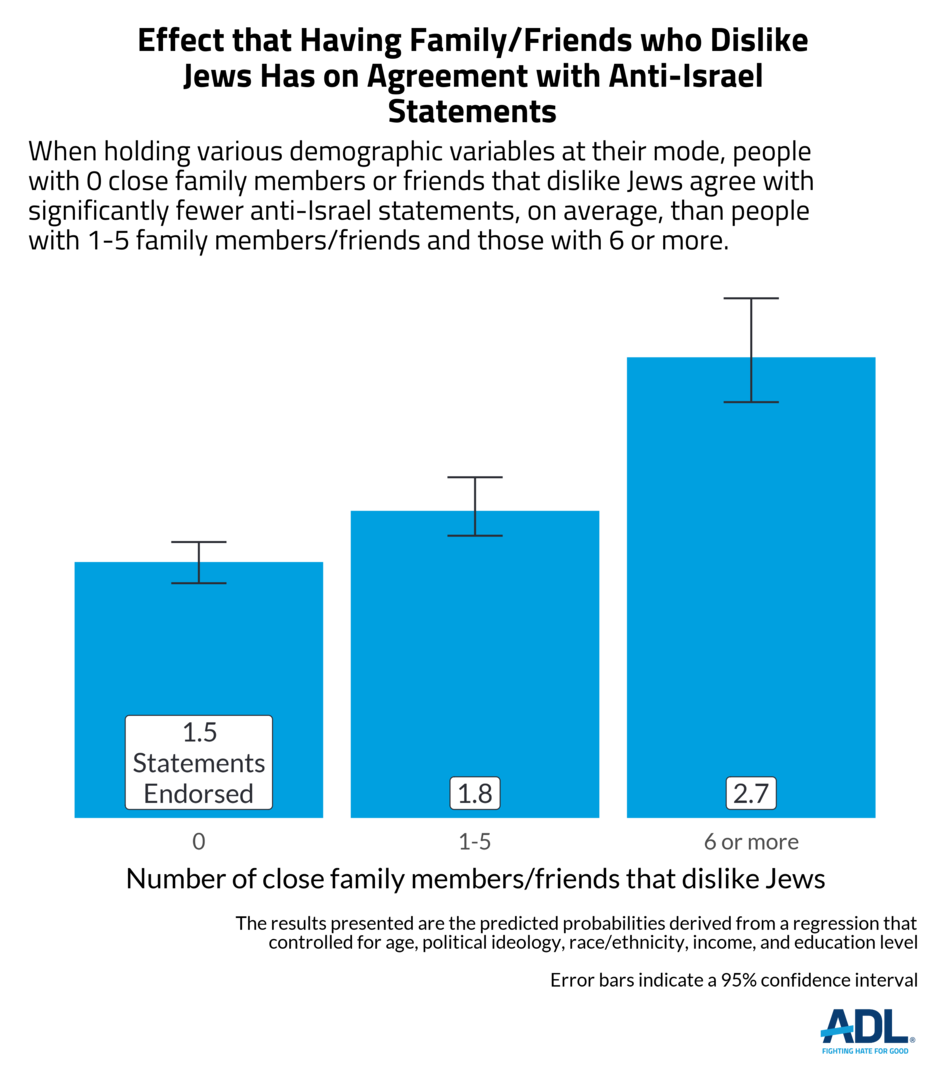

As was the case with anti-Jewish attitudes, researchers found that the number of one’s friends and family who dislike or like Jews had an impact on one’s attitudes towards Israel.

Respondents with more friends or family members who dislike Jews agreed with a slightly higher number of anti-Israel statements. Of the 8 Israel statements respondents answered, people with 0 close family members or friends that dislike Jews agreed with only 1.5 of them. This is fewer when compared to people that have 1-5, who agreed with 1.8, on average. Moreover, people with 6 or more family members or friends that dislike Jews agreed with even more. They endorsed on average 2.7 negative statements about Israel.

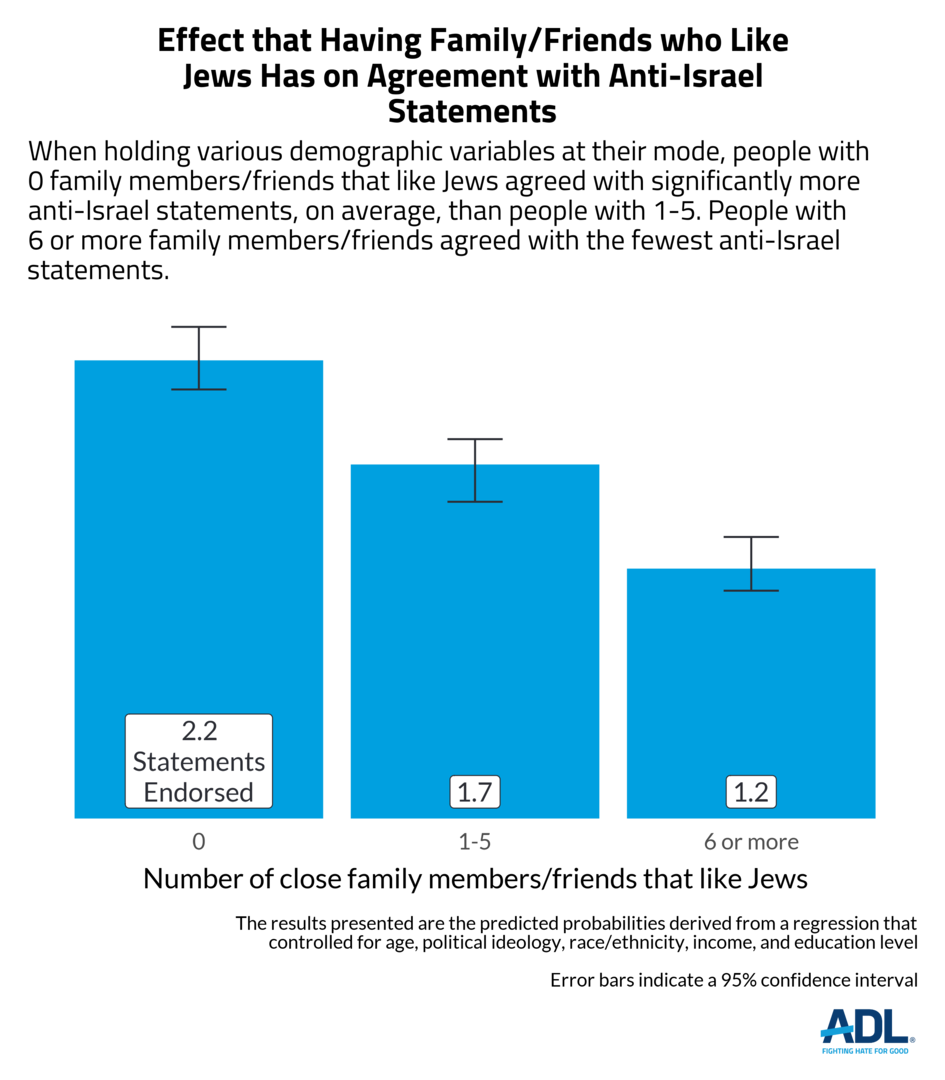

Similar to endorsement of anti-Jewish attitudes, people who report having family members that like Jews also tend to have more positive views of Israel. People with 0 close family/friends that like Jews agreed with the most anti-Israel statements, averaging 2.2 out of the 8 statements measured. This is significantly higher than people with 1-5 family members/friends who like Jews, who endorsed 1.7 statements. Those with 6 or more endorsed the fewest, averaging only 1.2 statements.

Conclusion

In sum, researchers found that one’s relationships with friends and family seem to play a highly significant role in driving one’s attitudes towards Jews and Israel. Although people report hearing anti-Jewish and anti-Israel comments from their friends and family less frequently than from other sources, these exposures appear to be the greatest predictors of one’s own beliefs and attitudes.

While this finding confirms much of the existing research on prejudice, it does have two intriguing implications worthy of further study. The first is that it appears far easier for people to label the comments of those most distant from their immediate social circle and least popular (e.g., politicians) as anti-Jewish than their family and friends. The second is that, despite this, the very act of labeling a friend or family member as someone who dislikes Jews is not enough to limit the predictive power of one’s own antisemitic beliefs. In other words, being aware that someone in your close social circle dislikes Jews and even reporting that on a survey is not enough to mitigate its predictive association.

Acknowledgments

The continued partnership of the One8 Foundation.

Research support provided by Graham Wright and Leonard Saxe of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University.