Related Content

Disruption and Harms 2020 in Online Gaming Framework

Welcome and Start Here

Introduction

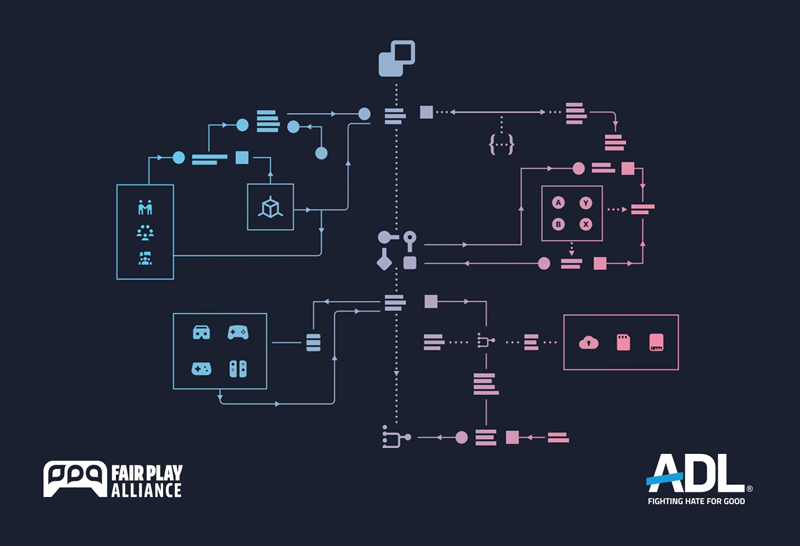

To synthesize our understanding of behavioural issues in gaming today, the Disruption and Harm in Gaming Framework arose through an unprecedented and global collaboration among the gaming industry, with support from leading researchers and civil society organizations. The result is a comprehensive framework detailing what we know about such conduct, including root causes and is the first in a series of resources that operationalise this knowledge.

While it is clear that there is much work ahead as developers, there is also much to celebrate. This project would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of many developers, community managers, and workers in varied roles across the industry to better understand and support players. It also would not exist without the growing number of studio efforts to help change how games are made and to promote safe and positive play environments for everyone.

This iteration of the Framework is the result of input from hundreds of developers and specialists worldwide in the gaming industry, civil society, and academia. Numerous hours have gone into interviews, working groups, research, synthesis, writing and iteration.

To everyone who has helped us get here: Thank you for your dedication to players everywhere.

Our work is far from done. We will continue to identify and lift up our industry's efforts and best practices, develop and share new resources, and iterate and improve the Framework with your help. By striving for a shared foundation, we unlock further collaboration and better alternatives to bring out the best in not just our games and communities, but society overall. Together as an industry, we must continue to create safe, inclusive spaces that allow players to be their authentic selves and celebrate the joy of playing together.

The Audience

Us! This Framework is made in large part by the gaming industry for the gaming industry. While not everyone will want to dive in extensively, we anticipate that anyone working in this space, or making decisions impacted by these issues, will find this framework informative. Given the critical nature of these issues, we hope developers will read this Framework and equip themselves with a deeper understanding of the problems and roles any of us can take to protect, support, and enhance player experiences.

The Authors

Production of this Framework was a collaborative effort between the Fair Play Alliance and the Anti-Defamation League's (ADL’s) Center for Technology and Society (CTS). Together, experts from both organizations strove to capture, catalogue, and synthesize the depth and breadth of behavioural issues that we see in games, known best practices (with more to follow), and incorporate the experience from those in related fields in addressing hate, harassment and antisocial behaviour in digital spaces.

What This Framework Covers

The Framework centres on four key axes of disruptive conduct we see as an industry across our gaming ecosystem:

- Expression—What form does it take?

- Delivery Channel—Where does it happen in and around online games?

- Impact—Who is affected by it, and in what ways? What are the consequences?

- Root Cause—Why does it happen? What does it express?

We are also introducing the first of a series of resources to help developers get started or improve their current practices:

- Assessing the Behaviour Landscape

- Planning a Penalty & Reporting System

- Building a Penalty & Reporting System

- Community Management Guidelines

Our intent is not to be prescriptive but to provide a shared understanding for developers everywhere. By raising awareness of these issues, we can advance a shared language and better inform product decisions, design, and moderation. If collectively taken forward, this Framework will help us ensure that we are comprehensive in building healthy, thriving communities as an industry.

Note: Since the “Disruption and Harm in Gaming Framework” has resisted a fun acronym, we will simply use “the Framework” throughout this document when referring to this initial release and its supporting resources.

How to Use the Framework

- Commit to our Call to Action below. Help us generate momentum across the industry and share back what you learn so we all can grow!

- Encourage key individuals to read the Framework and generate discussion. Be prepared to follow up and facilitate that discussion.

- Identify opportunities to improve player interactions that you may have in your existing or upcoming games and generate an action plan.

- Take advantage of our existing resources (and don’t be shy to request more).

- Join the FPA! We are available for consultation and support on any areas relating to player behaviour and healthy communities. If you are already a member, reach out to your colleagues through FPA channels to ask questions and share your learnings. Our partners at ADL are also available for support and guidance.

Industry Call to Action

This call to action is an important step in highlighting the gaming industry's ongoing efforts and showing our commitment to player health and well-being. By stepping up and showcasing our efforts, we help build confidence that the industry takes these issues seriously and generate momentum and support to help other gaming companies get started.

To participate, please share this Framework with your team and highlight key learnings or opportunities. Then, work with your team to commit to the following:

|

(A) Generate a list of actionable goals for a six-month time frame appropriate for your team and company. If you need help, consider the behaviour landscape assessment tool as a place to get started! (B) Share those goals with FPA members with a commitment to share your learnings publicly within six months. E.g. How are you making the framework part of your company’s process? How are you doing things differently and what are the results? How are you targeting specific behaviours? How have you used the tools provided and what you have learned (and how can we make them better)? |

Together, we can demonstrate the industry’s commitment to players and generate the momentum and support to bring change at scale. Every company’s commitment matters!

Other Ways to Get Involved

In addition to the Call to Action, we invite companies to support in the following ways:

- Reach out to the FPA and share your expertise or commitment to support further research. Do you have a process or recommendation that might help other studios? Are you actively working on a problem space identified here, the results of which you could share?

- Commit to partnering with the FPA to release a new resource in 2021.

Introduction

With the advent of reliable in-home networks and other technologies, online multiplayer games have become an ingrained part of our social tapestry. They enable us to make friends and escape the monotony and stresses of everyday life. Games bring people together through the power of shared experience—we can fight alien invaders, explore distant lands, plant a garden, or push each other in a shopping cart. At their best, games reflect the peak of humanity collaborating with one another, across what might otherwise be vast divides. Anyone can belong in a game, no matter where they are in the world—or if they never leave their home.

But peaceful coexistence can be challenging even in spaces designed for fun. Unfortunately, just as in non-digital life, social and behavioural issues threaten those experiences.

This Framework seeks to produce a unified resource that documents the many efforts of developers and publishers worldwide to understand behavioural issues in games, and the contexts and choices that influence them. We can then apply our skills as game developers to make games and features that foster healthier communities.

It is important to acknowledge that much of the disruptive and harmful conduct we see in games is rooted in deeper causes. The behaviour reflects many of the problems we see today on a societal level and points to a larger gap in our ability to coexist harmoniously in online spaces. And unfortunately, the surge of hate and discrimination we have seen around the world (both online and in the physical world), which seeks to sow division and incite violence has not bypassed online gaming. An increasing attempt to moderate and control behaviour is not a sustainable path.

We must look at how our decisions as designers impact the health and success of the communities we inspire, how we create spaces that foster compassion while better serving our core social needs, and finally, our role in helping the next generation become responsible members of gaming communities and beyond. Just as there has been a movement to create privacy by-design, so too can there be a movement to create “anti-hate” by design, not only without diminishing the competition and collaboration created by online universes in which players immerse themselves, but with the ultimate goal and impact of improving the unique collaboration multiplayer games offer.

This document is not the final word on these issues, but the start of a new conversation creating a clear, measurable pathway towards making online games respectful and inclusive spaces for everyone.

You will find additional resources in Part 3 and linked on the provided websites.

The Problem Space

Game developers are neither new to the interpersonal challenges of online play, nor have we been idle. This document is a testament to the industry's dedication; many companies today are devoting substantial resources to these challenges. However, much remains to be done. It is no secret that gaming spaces continue to be plagued by disruptive and harmful conduct.

ADL’s 2020 survey Free to Play? Hate, Harassment and Positive Social Experiences in Online Games found that 81 percent of adult online gamers in the U.S. experienced harassment in online games, an increase from 74 percent in the 2019 edition of the survey. Sixty-eight percent experienced severe harassment, such as physical threats, identity-based discrimination, sustained harassment, sexual harassment and stalking. Almost one in ten (9%) were exposed to white supremacist ideology.

We need to equip ourselves with an informed, unified language to understand the efficacy of our collaborative efforts. This Framework serves to fulfill that need.

Specifically, this Framework hopes to support developers with the following:

- A comprehensive framework of the disruptive and harmful conduct seen across the industry, including insight into root causes.

- An initial offering of resources that operationalise what we know so far, and lift up best practices for developers across the industry.

The Framework also sets up for future collaboration:

- Open questions and opportunities to address gaps or share additional knowledge that has not yet been covered here.

- Additional resources that help synthesize and share best practices for addressing the issues covered here, including fostering prosocial behaviours, attitudes, and player competencies, and opportunities to support the next generation of gamers.

- Opportunities to support smaller developers.

Part 1: What Do We Call Transgressive Experiences in Gaming?

Game developers most strongly align in protecting players from harm and bringing out the best in our games. Consistently and reliably assessing harm in the context of games, however, is incredibly difficult. There are many ways in which a game or a player’s experience can be disrupted.

At their least harmful, behaviours can be merely distracting or annoying. Such mild transgressions, though seemingly innocuous, are of interest to developers and community moderators. They result in poor experiences for players, disproportionately affect players who belong to vulnerable and marginalised communities, and create the conditions for more harmful patterns as players become frustrated and antagonistic interactions become normalised. At their worst, behaviours are damaging, such as child grooming, extremist rhetoric or potential radicalization, doxing, et cetera. There is no debate on whether these behaviours are acceptable: They’re unequivocally not.

In many other cases, what is acceptable versus what is not, or the level of acknowledged harm, can be at odds. Matters of interpretation, intent, cultural or regional appropriateness, legality, moral alignment, social cohesion, trust, and many more factors can all impact the assessed severity of the situation or even the ability to act.

At present, few terms are used by players, developers, researchers, the press and the public to describe the myriad disruptive or harmful actions a player might engage in or experience in an online game. What follows is an overview of the high-level terms used to describe these phenomena, their advantages and disadvantages, and the reasoning behind them.

In this Framework, we will use the terms disruptive behaviour, harmful conduct and respect to refer to conduct.

From Toxicity to Disruptive Behaviour & Harmful Conduct

Toxicity

In recent years, “toxic” has come to represent concerning behaviours and anything deemed unacceptable by a player or game company. It can ambiguously refer to clever plays against the opponent, ironic wordplay, the ribbing of fellow teammates, as well as more egregious offenses. “Toxic” can also describe the conditions that give rise to certain behaviours or how players think of a community. It can carry an incorrect assumption of fault —in some cases, players use the term to denigrate vulnerable and marginalised people, including women, the LGBTQ+ community and players who are or are perceived to be of certain races, religions or nationalities. The term fails to provide enough actionable information or useful feedback.

The lumping of all undesirable behaviours under a single term is a natural first response and echoes traditional social media's early days, when platforms such as Facebook put a wide variety of distinct behaviours under a single rule (see figure 1). Traditional social media now creates different rules and enforcement mechanisms based on the type of conduct.

It is worth noting that some studios have already defined the term more precisely for their internal use. We choose not to use “toxic” for this document because of the burden of its colloquial use. The goal of the Framework is to describe the granularity of behaviour types that we see; the problems we face are deeper than what the term toxic covers.

Disruptive behaviour

There has been a growing trend within the industry to use “disruptive behaviour” as the encompassing term for conduct that mars a player's experience or a community's well-being. It refers to conduct that does not align with the norms that a player and the community have set. In our conversations with developers, there is general agreement that this term is helpful because it acknowledges that not all disruption is necessarily harmful. It prompts further questions about what is disrupted, how or why the behaviour is disruptive, and the designer's intent for the game.

Using the term “disruptive behaviour” allows us to ask about the nature of a disruption in an experience and whether players' expectations were met, and even if those expectations were reasonable. Positive disruptions, such as exploring new avenues of play, might surprise or frustrate some players but are acceptable ways to engage with the game. Sometimes, they can give rise to whole new genres of play. Nevertheless, it is understandable how a player expecting one type of experience feels disrupted when encountering another.

Disruptive behaviour can arise from mismatched expectations. A group with different assumptions about playing a game unintentionally disrupts another group's experience, such as expecting a high-stakes match versus a causal one. But disruptive behaviour also includes more egregious actions like expressing hate or threats of violence. These actions might require mitigation by community managers, moderators, game developers and law enforcement.

As we look to instill healthier behaviour, we must distinguish between the goals developers have for games versus the existing community norms that inform players’ values and expectations.

Harmful Conduct

“Harmful conduct” is a subset of “disruptive behaviour." It describes behaviour that causes significant emotional, mental, or even physical harm to players or other people in the player’s life such as family and friends. This kind of conduct can ruin the social foundation of a game space. Such conduct can define or overwrite the norms of a community, creating an environment where egregious and damaging behaviors are seen, accepted and repeated in a game environment. If this is done without consequence, it can reach the point that those who are frequently targeted are pushed out of game spaces and those who stay are dragged down with the worst actors.

Harmful conduct can be context-dependent. While certain types of extreme conduct should always be considered harmful (doxing, discrimination based on identity, stalking), behaviours that are sometimes mildly disruptive in one context can be harmful in others. For example, while playing with a friend, it might be appropriate to type “I love you” into a chat. But the same message can become harmful depending on the recipient and the frequency of the action.

It is important not to conflate why a player does something disruptive or harmful (their intent) in an online game space with the impact the action has on a targeted player. Uncovering the intention of a player who engages in disruptive or harmful behaviour is different than supporting a player who experiences that behaviour as unwanted and harmful. We explore this further in the Framework and our supporting resources. In using harmful conduct, we refer less to the intended game experience or the intentions of players who are attempting to disrupt it, and more to the harm as it is experienced by the affected players. In other words, the focus here should be on impact more than intention.

From Civility to Respect

Civility

“Civility” is defined variously as “a form of good manners and as a code of public conduct“[ii] and “a polite act or expression.”[iii] “Civility” is often encouraged to improvebehaviour and harmful conduct online. It is desirable when people in digital social spaces give each other the benefit of the doubt and seek to understand each other’s point of view.

Unfortunately, civility implies a shared set of understandings between parties involved in a particular interaction. But who decides what is civil and what isn't? It’s important to consider power dynamics when establishing the vision of what we aspire digital spaces to be. Moreover, it is harmful to ask a person who has a marginalised identity to be civil to someone of privilege; it is emotional labor. The expectation for a person of color to remain calm and respond with civility to those subjecting them to racist abuse during a game is an example of civility's limitations.

Civility in digital spaces can look like “equality," giving people who come from different backgrounds the same opportunities without considering their unique positioning in society and set of lived experiences. Equality falls short of the ideal we should try to achieve in games. We should strive for equity.

Respect

Whereas “civility” can be seen as a version of “equality” in figure [x], “respect” is closer to “equity.” Respect means considering how each individual experiences a particular interaction, taking into account what they bring into the encounter. Respect is when a person feels their lived experience has been valued and appreciated—even if not fully understood. It is harder to give one broad definition to respect; what form it takes can look different from interaction to interaction depending on people's identities and the culture in which they exist, among other considerations.

Setting respect as a goal for online multiplayer games allows the conversation to be fluid about what a good or healthy community looks like: It depends on the players. Respect involves the perspective of the whole community. It allows for a rich exploration of the type of community a game company wants to create: What does respect look like for a team? For players? How do developers create a space that values everyone’s experiences?

Part 2: What Does It Look Like? Breaking Down Disruptive Behaviour and Harmful Conduct in Online Games

With the above context and terminology in mind, the following represents an initial framing of the problem space, focusing on the nature and severity of the occurrence, player motivations, and channels of harm that emerged from our initial interviews and working groups.

We have identified four key elements through which we can practically consider problematic conduct:

- Expression—What form does it take?

- Delivery Channel—Where does it happen in and around online games?

- Impact—Who is affected by it and in what ways? What are the consequences?

- Root Cause—Why does it happen? What is it an expression of?

Each element is complex and dynamic. In these elements we can break down many aspects of problematic conduct, from child safety to mental health and well-being to regional law and beyond. Almost all areas share some degree of overlap with other areas. Conduct emerges across multiple delivery channels and can range from the more common transient or disconnected incidents to strategic, coordinated attacks, such as hate raiding or denial-of-service-attacks, and can even end up impacting the target and people in the target’s life in physical spaces.

We explore each element in detail below.

Expression

In what way does the player engage in disruptive behaviour in and around online games? How is this conduct expressed in a game or game-adjacent setting?

How players express disruptive behaviour and harmful conduct can take many forms in online game environments. We want to describe these behaviours through the lists that follow so that designers can measure their frequency and think of ways to mitigate them.

This section's focus is on the categorical form that disruptive and harmful conduct can take, though you’ll notice some overlap with later sections. Each category is supplied with a series of examples reflecting the output of our industry-wide conversations but is likely not exhaustive.

What We Know

Descriptions of Conduct

Unintended disruption. Disruptive behaviour can be deliberate, for instance, when a player becomes frustrated or acts out of self-defense, but sometimes players are unaware they are ruining others’ experiences. Examples:

Players misunderstand game roles, strategies/tactics, or “metagame,” resulting in contradictory play.

- There is miscommunication due to language or cultural barriers or other communication difficulties.

- Players do not realize a word or phrase they use has an inappropriate or hurtful meaning.

- There are misaligned interpretations of the goal, such as seeking a high “kill count” or score instead of taking the point.

- Players use a game more to hang out versus collectively trying to meet objectives.

- Players reasonably try out a new strategy that other players do not anticipate or opt into.

- A mismatch of skills. Players placed at the wrong skill band who are otherwise trying their best; players at the correct skill band but who are experimenting with a new character or technique.

- There are new players who do not know how to play yet.

- Players not realizing that their actions have a negative impact on other players, such as when the game does not make such interactions or consequences apparent.

Aggravation. Pestering, bothering, annoying, griefing, or otherwise inhibiting another player’s reasonable enjoyment of the game. Examples:

- Loot stealing.

- Intentionally doing something that is counter to the team or party’s intention.

- Nuisance gestures, such as “teabagging,” or saying “ggez.”

- Interfering with a player’s ability to move, such as body blocking or preventing fast travel.

- Relentless pinging or messaging.

Antisocial actions. Often the most difficult to categorize and measure, antisocial actions refer to how certain overly antagonistic, alienating attitudes can manifest in the context of the game. While the individual behaviours might not be as problematic as others, together they negatively impact the health, feel, and cultural norms in and around the game. Antisocial actions and attitudes reduce players’ overall resilience and the broader community, encourage negative behaviour, drive away players, and increase the chance of escalation toward more serious behaviours and risks. The hallmark of such problems is generally captured in how new players are welcomed, how mistakes or undesirable outcomes are treated, and a tendency toward antagonistic or aggressively defensive remarks. Examples:

- The display of negative and unwelcoming behavioural patterns that affect the overall feel of a game and community, such as dismissing new players as “noobs” or suggesting they “git gud.”

- Players who make regular negative comments about the state or skill of the party or team, calls for surrender, or disproportionate responses in the face of hardship.

- Comments on bad plays, offering “advice” in the form of microaggressions.

- Players who generate interpersonal conflict, such as expressing unreasonable expectations of how others should behave.

- Interpretations of otherwise innocuous situations as players being intentionally harmful.

- Players who address pleasantries with hostile responses (e.g. a “hello” on joining a server that is greeted with “f*** you”).

- Players who engage in excessive blaming and show a lack of personal responsibility within a game.

- Players who show a general disinhibition or hostility toward others, such as flaming, insulting, or attacking without reasonable provocation.

Abuse of play/antagonistic play. Any type of play that is antithetical to the game’s intended spirit, and is unprompted or retaliatory (more detail follows in the section on causes).

Note: Some conduct can be misinterpreted as abuse, but can stem from a misunderstanding of the game’s rules or expectations, a lack of clarity of what is expected by the game itself, or rigidity among members of the community regarding “how to play.” See Unintended Disruption.

Examples:

- Trolling—deliberate attempts to upset or provoke another player, or inject chaos.

- Sabotaging—the failure to play, stalling, wasting time or roping (running down the clock), intentionally losing/dying, abandoning all or in part of a game, disclosing information to give an advantage to the other team.

- Spoiling—ruining in-game moments for other players, such as revealing the plot or other surprises intentionally.

- Abandoning a match, including ‘rage quitting’ (losing your temper and leaving) or quitting to deny a player their victory. Many games will default to a victory for the remaining player when possible, but they are still denied the experience of playing and the value of their time spent in the queue.

- Game mechanic exploitation to harass or grief another player—body blocking, spawn camping, banning a character another player wants to play, refusing to heal, loot stealing, or destroying ally resources.

- Abusing emotes, pings, or other expressive mechanics with the intent to annoy or disrupt other players.

- Smurfing—a player creates a new account to dominate inexperienced players (often called “steamrolling”). Smurfing is often accompanied by other forms of expression intended to intimidate or harass. Note: There are legitimate reasons that a player creates a new account, so exercise caution before concluding they wish to smurf.

Cheating. Exploiting the rules of the game to gain an advantage or disrupt play. This includes individual cheating and leveraging AI to cheat at scale. Examples:

- Bots, including aim bots, wall hacks, and GPS bots.

- Manual or automated farming or leveling, including boosting, deranking, and the sale of accounts.

- Director problem (exploiting the limited player pool at the highest tiers of play to force certain matchups).

- Manipulating ping or net code (playing at a high ping so it is hard to be targeted).

- Loot/item finders.

- Hacks that defeat enemies automatically or remove them from a level or quest.

- Exploiting a cheat code or other “back door” to manipulate game stats or settings.

- Data scraping, such as targeting servers or decompiling game code to compile game details that should not otherwise be known.

Harassment. Seeking to intimidate, coerce, or oppress another player in or outside of a game. Note: While not all harassment is hate-based, there is often significant overlap with hate as an expression. Examples:

- Hostage taking, such as “do this or else I’ll throw the game,” or someone threatening to harm themselves if another player does not abide by their wishes.

- Baiting players to misbehave, such as “say X 5 times or I’ll throw this game” in order to trigger a key-word detector.

- Instructing others to self-harm.

- Mobbing (a group bullying one or more individuals).

- Gaslighting. Intentionally undermining another’s sense of reality, causing them to question their thoughts, memories, and interpretation of events.

- Negging. Back-handed compliments or comments that may contain a compliment, but critically are framed in a way that calls someone’s value or worth into question. E.g. “Playing that character you didn’t suck as much as usual”, “You did OK for a girl”.

- Abuse of personal space (especially in virtual reality).

- Rules policing or enforcement, such as harassing someone for playing “incorrectly,” playing poorly, or justifying the use of harassment because of someone’s poor play.

- Harassment offline based on a game someone played (this can be worsened when players cannot reliably opt out of revealing when they’re online).

- Identity-based harassment (this overlaps with hate, described below)

- Developers, moderators, community managers, influencers or professional players who behave inappropriately or unfairly in their responsibilities, such as rallying their audiences to harass players or developers.

- Benevolent harassment, such as helping another player who identifies as female ostensibly with good motivations but in reality because they do not view that player equitably.

- Defending the exclusionary nature of a game or denying access to certain social groups or marginalised communities. For example, by asking inappropriate and personal questions or displaying unwelcoming conduct.

Hate. Verbal or other abuse, including intimidation, ridicule, “hate raiding/mobbing,” or insulting remarks based on another player’s actual or perceived identity (e.g. race, religion, color, gender, gender identity, national origin, age, disability, sexual orientation, genetic information, disability). This can include “dog whistles,” defined as the use of subversive or coded messaging around hateful activity to avoid detection from game developers or moderators.

Extremism. A religious, social or political belief system that exists substantially outside of belief systems more broadly accepted in society (i.e., “mainstream” beliefs). Extreme ideologies often seek radical changes in the nature of government, religion or society. Extremism can also be used to refer to the radical wings of broader movements, such as the anti-abortion movement or the environmental movement, but in a contemporary context often refers to White Supremacy. ADL’s 2020 survey found that nearly one in ten (9%) of adults who play online multiplayer games are exposed to discussions of white supremacist ideologies.

Dangerous speech. As defined by researcher Susan Benesch and the Dangerous Speech project, this is content that increases the risk that its audience will condone or participate in violence against members of another group. Examples:

- Content that dehumanizes members of a group (comparisons to animals or insects, etc.).

- Content that portrays the target group as violating the purity of the intended audience of the content, making violence a necessary method of preserving one’s identity.

Inappropriate sharing. Any sharing of information or content that is uninvited. Examples:

- Memes with hateful or discriminatory content.

- Sowing disinformation or information intended to mislead.

- Posting inappropriate links, including malware, dangerous websites, advertising exploits, etc. Many companies do not allow players to text links as a preventative measure.

- Spamming, such as excessive sharing of a phrase, link, or emoji to promote disruptive or harmful conduct.

- Using bots to facilitate inappropriate sharing or circumvent preventive measures.

Criminal or predatory conduct. Conduct that should be escalated to law enforcement and have criminal repercussions. Examples (not meant to be comprehensive):

- Stalking (including cyberstalking).

- Identity theft.

- Threats of violence.

- Redirection of civil services (including law enforcement) to harm others, such as swatting.

- Grooming.

- Intentional sharing of personal information to incite injury, harassment or stalking, i.e. doxing, or calls to dox.

- Blackmail or soliciting information with the intent to harm or coerce.

- Fraud or scamming, including phishing, account stealing, bad trades, and theft.

- Deception or impersonation, such as pretending to be game company staff.

- Organized harmful conversations and some forms of dangerous speech (see above).

What We Don’t Know

Where is the line?

With some exceptions, the line between a non-harmful disruptive expression and harmful expression depends on context: Where did the communication take place? Between whom? At what frequency? In what kind of game? What cultural expectations have been set by the game developer?

Take, for instance, discovery and building games, celebrated for fostering creativity, constructive thinking, and teamwork. These games give players the freedom to build their dream creations; they also permit players to create objects of hate. Companies must swiftly address hate, but questions arise. Do developers take away the creative core of the game to address hate? What if those objects are in a private setting with no exposure to other players? What if those creations are exposed through external social tools?

Players have expectations for games. If a player shows up to a basketball game only to throw the ball out of bounds, other players will reasonably want that player removed—that person’s conduct disrupts the game. Sometimes, game rules can reassure players' expectations will be met, but the inherently creative and often personal nature of games can make anything except the most obvious rules impossible. In the basketball example, what if the players had all agreed to play by alternate rules?

Every game genre carries different expectations. What is considered acceptable “smack talk” among players of fighting games is very different from the acceptable interactions in social-simulation games—even subcommunities within a genre sometimes differ in their expectations. It is not uncommon for player subcommunities to arise as safe spaces for marginalised groups because they use a different parlance not accepted by the broader community. Players new to any game or genre might unintentionally violate these norms, and are likely to adapt quickly to whatever is dominant to fit in, making community expectations often self-sustaining.

Drawing strong lines in the face of harmful conduct can be difficult and frustrating. We need to continue identifying and assessing behaviours and think about how we develop healthier communities in the first place. The line developers draw as to what is acceptable in games should be carefully considered, in consultation with internal experts, researchers, and civil society. It should be reevaluated as language and expressions evolve, norms change, and online game communities grow. We must remain conscious of our own biases as developers and how we best tune into player needs.

Delivery Channel

What channels are in use for a harmful or disruptive activity? How do players encounter this conduct in a game or game-adjacent space?

Disruptive or harmful expression can occur anywhere in or adjacent to a game environment, so it is important to consider the delivery channel and how that affects its presentation. If we only look for hate and harassment in text logs, for example, we miss other critical channels such as voice, game mechanics, or user-generated content. Understanding where players show disruptive behaviour will help us create better tools for detection and monitor our communities' health and well-being. The line is not always clear where an Expression ends, and its Delivery Channel begins. This section aims to highlight areas to be mindful of when assessing your game or planning for future games.

What We Know:

Vectors of Disruption and Harm

In-game communication

- Text chat (open game, team-based, guild-based, lobby, individual).

- Voice chat (it is not recommended to have voice on by default among strangers).

- Emotes, pings, stickers.

In-game mechanisms

- Game mechanics (e.g. body blocking, sabotage).

- Game manipulation or cheating.

- Character-as-proxy (e.g. “teabagging,” or invading personal space in virtual reality).

- In-game objects and imagery, including avatars and UGC.

Meta-game systems. Any conduct within the non-gameplay aspects of a game, such as the progression system, store, guild, etc., and is not separately called out elsewhere

- Bots/automated systems.

- Fake or malicious reporting, abusing tools or services with the potential to disrupt or harm another (e.g. abusing vote-to-kick).

- Using game channels to advertise or monetize inappropriate technology or exploits.

- Stream sniping (attempting to join an actively streaming game to harass a streamer).

- Guild-on-guild harassment or antagonism through guild features.

- Harassment via the “friend” ecosystem.

- Inappropriate player, team, or guild names.

Broader ecosystem. This includes the larger gaming ecosystem outside of the direct game or meta game, including streaming and community websites.

- Social media (e.g., stream sniping, mobbing)

- Live streaming and accompanying social features (e.g., chat, other feeds)

- Manipulation of civil services, including law enforcement (e.g., swatting)

- Direct harassment out of a game (e.g., email, texting, traditional mail)

- Networked harassment (e.g., organizing swarm effects or mass harassment).

- Player support or customer service

- In-person events (e.g. competitions, conventions)

Direct targeting of a studio, employee, or game service

- Review bombing

- Social-media bombing

- DDOS attacks

- Hacking or malware

- Doxing

- Stalking

- Physical harassment or threats to physical safety

What We Don’t Know

What can game developers do for spaces related to their games that are not directly within the games themselves?

While online games are social spaces in and of themselves, there are many other spaces related to online games where disruptive and harmful experiences can occur, many of which are listed above. These range from community forums to in-person events, such as fan conventions or competitions, to various social media platforms and more. While it is clear that we should uphold the values we want to see within our communities, what is less clear is a path to doing so when many of these spaces are out of our control.

Healthier game environments will come from stronger alignment and ongoing efforts throughout the industry to establish expectations. The industry should adopt a firm stance against hate and harassment. Universal access to tools and platform-level resources could help detect and address issues. Being intentional about fostering respectful communities in and around games can set expectations that then inform the broader ecosystem.

It is worth considering how much moderation should come from community managers and developers, and how we equip communities to self-moderate. What tools do we need to provide? What does good self-moderation look like? How do we sustain a healthy community? When, if ever, should out-of-game conduct result in in-game action by the company?

Finally, there is much to be done to address the issues we see on a societal level systemically. As developers, we can better support players' well-being through schools and community programs while continuing to create digital spaces that meet our need to play and socialise.

The hope is this Framework will support these efforts, as will our resources (such as the Behaviour Landscape Assessment tool).

Impact

What is the impact of these behaviours? Who is disproportionately affected? What are the short- and long-term consequences of this behaviour for players? How can we better assess harm? How can we better understand players?

Disruptive behaviour can alter an online multiplayer game's social dynamics in ways that developers never intended, bleeding into other online or offline spaces. The behaviour impacts whether someone continues playing a game. It can affect a player’s personality, emotional state, and their safety. It can also impact their financial status, their family and their career and future employment opportunities.

There is often a gap in understanding the nature or severity of the harm. Conduct can harm the player or players targeted, and manifest directly or indirectly. Established community norms mask problematic behaviours if players become acclimated to them or drive away those who speak up.

An individual player's context and well-being also increase the risk of harm, highlighting an opportunity to introduce mental health resources to players across the industry.

|

Look for opportunities to destigmatize mental-health problems and direct players to resources in their area. In general, it is good practice to provide links to resources for players who need mental-health support and prepare for support tickets that require escalation to assess the risk for self-harm. Consider the excellent work of organisations like Take This, a nonprofit promoting players' mental health in games. |

This section summarises many of the impacts as we know them today. We cannot reasonably address all of them, but we agree that we want to fix the ones we can, and support those affected. These are the right things to do, and they will help us all grow successful businesses.

What We Know

Who can be impacted by disruptive behaviour or harmful conduct in online games?

Potentially Impacted

Disruptive or harmful conduct does not only affect players. As developers, we need to think about how our efforts might impact different groups:

- Players

- Content moderators

- Developers

- Game companies

- Community managers

- Influencers

- Media

- Parents, teachers, caregivers

- Friends and family

- Potential players

- Employers and Collleagues

Potential Target Vectors

A player may be exposed to the impact of disruptive behaviour or harmful conduct for several reasons. The following are particularly common:

Identity. Individuals can be targeted because of their actual or perceived age, race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, national origin, disability.

Game-related roles. Certain jobs have more exposure to disruptive behaviour and harmful conduct in online games such as community managers, content moderators, journalists, and influencers. We need to think about how we best support people in these roles (see Out-of-Game Consequences below for more information).

Skill. Players often target other players based on their skill in a game, especially if that skill level is perceived as sub-par. On the other hand, extremely skilled players are given a pass even when engaging in disruptive behaviour or even harmful conduct.

Radius of Impact

Direct

- Immediate target

- Co-located bystanders

Indirect

- Indirect bystanders (exposed via media, clips, news coverage)

- Non-players, like caregivers, family, friends, employers, colleagues

- Developers

- Frontline support (e.g. player support, community managers, moderators, tech support, regional company representatives, event staff)

- Audience (players for whom the game is targeted or not)

Aggregate/norm setting

- Over time, players who are impacted by online hate and harassment make play decisions based on their experiences or the reputation of a game community, such as only playing with friends, single-player modes, or never using voice chat. These patterns can become the dominant playing style and are hard to change even once the root cause is addressed.

- A studio's or game's reputation that influences player behaviour (e.g. “X game is toxic,” “X game has the worst players”).

- Cultural, genre, and game norms shape thinking and expectations that impact a game even before launch, or reinforce an outdated reputation.

- The studio's understanding or expectation of its target audience can inadvertently drive norms, such as misidentifying a target audience and then making decisions that create a limited audience (a “self-fulfilling prophecy” effect).

- The playing community's environment can significantly influence norm setting, such as how parents or the media project their views onto this community and its active participants.

Gameplay-Related Consequences

Manage community of play. Some players prefer to only play with someone they know, possibly due to previous experience with disruptive behaviour from unknown players and a lack of trust in online game experiences.

“I exclusively play with groups of gamers I’ve built up trust with and if they invite someone new in, I’m generally mute.”[i]

Quit or avoid playing certain game modes or genres. Some players decide to stop playing certain games or game modes, or switch to single-player games exclusively. Others avoid games or genres due to their reputations, creating situations where the players who remain become hardened or desensitized through exposure, making it challenging to change those patterns or invite disaffected players back. For online games to continue growing, it is crucial to find effective ways to support targets of disruptive behaviour before these situations occur, especially if they belong to traditionally marginalized communities.

Change engagement or communication patterns. Players respond to disruptive behaviour by altering their modes of play. Voice chat reveals details about a player's identity, and they might decline to use the function out of fear of being harassed.

“I don’t talk on the mic, I just play… I just stopped talking cuz they’d be like, ‘oh that’s a girl, let’s harass her or ask for her number or something.’”[ii]

Out-of-Game Consequences

Psychological and emotional. Experiences of disruptive behaviour in online games can inflict psychological harm on players of all ages. Players socialise less, feel isolated, and have depressive or suicidal thoughts.[iii] Incorporating research on how to help players struggling with their mental health is worth considering.

“I don’t care [pauses]. Well, let me rephrase that. I mean, I cared about it for too long. . . . Ignorance is exhausting to deal with. . . I’ve heard it for so long, and I harbored a lot of resentment against these strangers I would never meet in my life. I had to make it stop hurting.”[iv]

“My self-esteem is already so low so I couldn’t handle talking and then the abuse that would happen” (post number 132)[v]

The inability to fully automate assessment, and the imperfect nature of automated systems, means that content must be reviewed by a person or go unaddressed. In addition to the players who are targeted and impacted, content moderators experience a disproportionate amount of troubling content and player abuse. The psychological toll of content moderation is enormous, ranging from desensitization to self-harm, and might not be immediately apparent. Stress suffered by content moderators is not unique to gaming—the lessons from other online platforms, such as social media, serve as stark warnings.[vi],[vii].

Relational. Disruptive behaviour hurts players' relationships with others in the game community and outside of it. Personal relationships are affected, a person's behaviour changes, or there are troubles at school or work.

“When I grief, it is usually act [sic] of revenge. If someone does shit to me and I clearly see it was not an accident, I will surely retaliate.” -Otto[viii]

Physical safety. In the most extreme cases, players targeted by disruptive behaviour (crossing the line into harmful conduct) feel physically at risk and need out-of-game support to assure their safety. Players who have these kinds of experiences sometimes take steps to protect themselves and their loved ones, such as changing the locks or installing a security system or contacting the police. Developers must do everything we can to protect players and remove them from risk.

Retaliatory or defensive behaviour. Players retaliate if they feel they have no other recourse or believe it is an acceptable way to address problems. Retaliation can increase harmful conduct.

What We Don’t Know

How do we best measure impact? What are the long-term implications for players and games? How can games support targets of disruptive behaviour and harmful conduct?

Assessing impact can be difficult. Not all players are willing or able to report on their experiences, and we often lack reliable measures to understand these impacts at scale. A decrease in player reports, for example, may falsely indicate an improvement in the overall well-being of a community. In reality, however, it could be that players do not trust the reporting tool, do not believe their report will matter, or those affected are taking extended breaks or leaving the game altogether. It is always important to consider the bigger context in which a game is played and develop more comprehensive measures that look for indirect signals. A combination of measurements—reporting rates, qualitative assessments, actual incidents, the impact of exposure to incidents—gives developers a much clearer picture of problems that drive away players.

Categorizing how online game spaces impact people does not address the long-term effects and implications. It is unclear how many gamers have quit or potential gamers have never played because of the prevalence of disruptive behaviour and harmful conduct. We neither know the impact of incidents on players after they leave nor the severity of negative experiences in online games compared to similar situations in other digital social spaces.

Community moderation remains predominantly focused on perpetrators. It is unclear what mechanisms most improve a player's experience once they have been targeted in an online game. What will keep them feeling safe in a game community or help them regain a sense of safety? How do we nurture robust communities with stable norms that prevent abuse? How do we promote character development among young players so they show greater empathy and respect toward others? More research is needed to find these answers.

The industry should be aware of the disproportionate impact on marginalised groups since existing metrics can fail to capture the harm done to those communities in game spaces, as well as inadvertently reinforce bias among both staff at game companies and players in game environments. For example, if some such groups are overlooked as a potential target audience by developers for a game or genre, it can result in pushing that community further away from a game or genre, due to previous experiences of mistreatment through and by games. This oversight shrinks our potential audience and hinders our ability to foster healthy, inclusive communities.

We must quantify and communicate the impact of harmful conduct on business; it affects retention, lifetime value (LTV), and player acquisition, among other metrics indicating success. It can be difficult to assess the extent of the impact and to determine its causes, thus it is necessary to track incidents and see what happens to victims. Do they mute their audio in this or future sessions? Do they change their play patterns, such as a longer delay before playing again after exposure? Or cease playing the game?

The general public, not only game developers, needs to understand the long-term impact of online abuse. Mounting evidence shows the lasting negative effects of this abuse on mental health and feelings of safety. The trauma suffered from harmful experiences hurts an individual's ability to be successful in online spaces, critical to how we interact with each other today.[ix]

It must be a high priority for the industry to develop and share best practices to identify the impact of and reduce online abuse. Engaging with researchers is an excellent opportunity to establish such standards.

Root Cause

What do we understand about the conditions driving these behaviours? How can this understanding inform our ability to reduce harm?

Fostering healthy communities should not be reduced to an enforcement enforcement arms race where we focus only on increasing content moderation. Perhaps the most critical task ahead for our industry is to understand why these issues surfaced in the first place. When we developers can identify root causes, we gain insight into how we influence player interactions and spot the challenges ahead. As a result, we can design spaces that serve our core human needs and set up the next generation to flourish in online spaces and beyond.

A game's environment influences behaviour. As diagram [n] illustrates, players are affected by various factors such as developer interaction, community boards, or a game's level of friction. The player's life outside of games matters, too. Their mental health, maturity, resilience, and access to a supportive environment all exert a role.

Developers might have to spend extra effort to offset behavioural patterns encouraged by the game's style or intent. That’s not to say that developers should avoid designing these games altogether, but it is useful to understand the patterns in order to prevent disruption and help players maximize their enjoyment.

The following is an overview of root causes and the contexts that drive them.

What We Know

Many factors contribute to why disruptive conduct occurs or becomes normalised. Game developers cannot address all the factors, but we can contribute to more effective responses.

In-Game Factors

Game design and affordances. Games can have mechanics that are antagonistic or antisocial. Recognising these aspects can direct developers on where to put in extra effort to smooth over player interactions or understand how problematic patterns emerge so we can intervene[x]. Considerations include:

- Competitive games tend to foster an antagonistic attitude or negative interpretation of others’ actions.

- Unnecessary sources of conflict, such as zero-sum resources, generate antagonism between players rather than enhance the game experience—especially problematic for strangers who have no pre-existing trust or shared understanding that would facilitate a more peaceful resolution.

- Games incentivise exploitation and pushing limits. Developers often create situations that encourage players to optimise their play, yet punish them when they do so (such as spawn camping, or smurfing). A difficult tension arises, and not everyone can equally opt into the playing experience (such as those being camped).

- Developers need to set players up for success in games and help them develop healthy habits.

- Mechanics or objectives that interfere with other players either intentionally or through their regular use.

Behaviour expectations. A player’s understanding of what is expected of them and their peers in a game space influences their behaviour. For younger players, this includes the ability of their caregivers to support their personal growth. Considerations include:

- Inconsistent enforcement. Consistency of enforcement across all players, regardless of status, is important in setting expectations and avoiding double standards.

- Accessibility of reporting functionality, choice of reporting categories, and surrounding language all inform player expectations. Show players that their reports matter.

- Inconsistent messaging in player communications, reinforcement of poor behaviour through direct and indirect reward mechanisms, and the absence of channels to report can tacitly approve of transgressive behaviour.

- The Code of Conduct, including accessibility and presentation, can provide a path to consistent enforcement through a shared language for expectations among players and staff.

- Providing specific, actionable feedback to players in warnings or penalties increases individual player accountability, reduces appeals, and lowers recidivism.

- Community and genre norms influence what is deemed acceptable or necessary to fit in. We must increase the diversity of gaming spaces while leaving room for self-expression and bonding (see also Out-of-Game Factors).

- Aim to capture the spirit of a rule with a few illustrative examples, rather than attempting an exhaustive list of exactly what to do or not to do. Help players understand what expectations and what they can do differently in the future if they do something wrong.

- Some behaviours are too ambiguous to label as acceptable or problematic. There is a blurry line between activism and harassment, banter among strangers versus friends, or joking and abusive taunting based on the kind of game played. For example “smack talk” is acceptable in fighting games but offensive in first-person shooters.

Game theming and tone. People absorb their social surroundings. Thus the tone and setting of a game will influence community patterns and how to approach antisocial behaviour. Considerations include:

- Games designed around behaviours such as raiding, theft, ambushing, or cheating can make it harder for players to relate to each other. In contrast, games with more prosocial and empathetic themes expose players to healthier habits.

- Characters with antisocial personalities can influence a player’s thoughts.

- Overrepresentation or underrepresentation of characters. A subgroup's preponderance in games encourages gatekeeping, sending an incorrect message on who belongs in gaming communities.

Out-of-Game Factors

Social, cultural, or civil context. Games do not exist in a vacuum. A player's social context matters. The transactional nature of games, pressure to react swiftly to a situation, or the blurring of political or cultural boundaries can lead companies to set precedents with unintended consequences. Considerations include:

- Cultural clashes—regional differences, conflicting beliefs or values, words with different meanings.

- Nationalism/patriotism can lead to an “us vs. them” attitude.

- Extremism and understanding how extremist ideologies manifest in a particular social and cultural context.

- Legal, political, or cultural stances regarding vulnerable and marginalised communities

- Inequality or power imbalances.

- Current events, especially civic unrest, and the growing presence of activism in games.

- Shifts in meaning due to world events. Consider pre-9/11 versus post-9/11, pre-Covid-19 versus post-Covid-19, or imagery adopted by hate groups, such as Pepe the Frog.[xi]

- Gender, the norms of which vary considerably from region to region.[xii]

Power dynamics. The power dynamics among players and developers influence game interactions. Not all freedoms and privileges are shared equally, so people in positions of privilege fail to recognise their views do not represent other perspectives. Abuse of power is when a person’s status harms or further disadvantages others. Considerations include:

- The form that harassment takes changes relative to the position of power.

- Top player or influencer privilege—how popular you are affords certain advantages, including protection from the rules in some cases, creating a dangerous inconsistency.

- As the makers of games or platforms, developers hold a position of power relative to players. We are likely to make assumptions about the experiences of players and show bias against subsets of players.

- Certain choices, such as using nationalities as identifiers in games can exclude players.

- Imbalanced relationships. One-sided relationships form around well-known players or influencers, leading to problematic conduct among fans who harass celebrity players or celebrities who abuse their position.

- Underrepresentation, especially of vulnerable and marginalized communities, through characters, settings, and player avatar options.

- Violations of the contract of play can arise from power imbalances. For example, trolling other players as a motivation of play.

Note: Developers can model healthy behaviour and compel others to do the same, such as coaches, influencers, and pro players.

Compatibility. The compatibility of players is a predictor of successful interactions. It determines player reciprocity, alignment on expectations in playing a game, and what players think of each other. Considerations include:

- Factors like age, personality, experience, skill, maturity, or social norms.

- Familiarity. Do players know each other? Is this a friend group with a pre-existing way of communicating? Are there outsiders in the party, but not in the friend group?

- Matchmaking uses skill or availability to select players. Opportunities exist to provide richer environments that help players get to know one another and make informed choices on whom they pick.

Health, well-being and personal development. Fundamental aspects of human psychology and sociology predispose us toward certain behaviours. A player's well-being, plus the health of the surrounding community, determines their attitude. Players who turn to games for solace might find the opposite waiting for them if disruption and harm are present.

Players’ ability to thrive

- Physical and mental health.

- Agency, resilience, social and emotional competence.

- Self-actualisation and general success in life.

- Love, trust, support, and a sense of belonging.

- Individual perceived agency and motivation.

Mentality/attitude

- Cognitive biases[xiii] (e.g. Dunning-Kruger effect, fundamental attribution error).

- Perceived threat or reactance, such as resistance to being told what to do.

- Defeatist attitude, or believing you are in some way disadvantaged or do not possess the skills to overcome adversity.

- Attention seeking, which can come at the expense of others.

- Divisive or domineering personalities who invite drama or overtly push their point of view.

- Fear, such as not wanting to risk the place you feel safe, or your standing in that space.

- Quickness to anger, defensive attitude.

- Social pressures, such as the desire to conform or status-enhancing behaviours.

Interpersonal maturity

- Can digest information in a productive way.

- Can respect different perspectives and understand the impact of one’s actions in a broader cultural context. Failure to do so can be seen when an individual claims an inappropriate statement was “just a joke” or otherwise denies its impact. It’s worth noting that when such behaviour is called out it can trigger individuals to react defensively, meaning the choice for how and when to give feedback can impact its outcomes (more detail is covered in Building a Penalty & Reporting System).

Community well-being, including resilience and social cohesion.

- Low resilience or cohesion, which leads to a loss of solidarity among members, or a tendency to be easily influenced by negative forces.

- Willingness to welcome new members and meet their needs.

- Entrenched attitudes and behaviours patterns will influence a community’s capacity to change. In some cases, change is not feasible and thus fostering a new community built on healthier foundations is best.

Societal health and well-being

- Systemic hate, civic unrest, and other problems within a game can manifest as a result of societal issues. These sociological factors will provide the backdrop to any behaviour efforts and their impact must be considered.

- Societal systems (education, health, and local community services) and how they are equipped to meet current player needs (and those of their broader community) can predict the stability and health of a gaming community.

Mechanisms of Identity. Identity plays a vital role in how we relate to one another and how we form connections; it can also be a channel for harm in unexpected ways. Developers need to think carefully about how we support player identity, lift up underrepresented voices, and keep players safe.

- The role of identity terms. Terms can be important to a community, but abused by people outside that community. How developers treat these cases can impact how safe players feel as members of marginalised communities.

- Players with multiple marginalised identities experience compounded harm (i.e. women of color)[xiv].

- Identity is forced as the subject of conversation or aspects of one’s identity are revealed inappropriately.

Game/company reputation and player trust. The reputation of a game or studio can significantly impact the expectations players bring to a game. A lack of trust influences a player’s behaviour and motivation to report other players. Considerations:

- Rare yet conspicuous behaviours give the impression that such conduct is frequent or acceptable. Failure to address such cases can lead players to think developers are not doing enough.

- The absence of tools to address unhealthy behaviour, or allowing it to spread, can make it feel acceptable. Failure to install tools prevents change and does not compel players to use tools that could be introduced later. Players do not think the behaviour is a problem because they are so accustomed to seeing it.

- Past statements or choices by a developer causes players to interpret an intervention as ineffective or insincere. For example, the misconception that a company is doing nothing when behind the scenes, it is working hard to deal with problematic behaviour.

- Inconsistent enforcement. If a company supports players who are being harassed, but does not hold sponsored influences accountable for harassment, this will significantly undermine the efficacy and authenticity of its efforts.

Limits of Digital Spaces

The relative newness of digital spaces has meant social protocols within games have not developed on par with face-to-face communication, where norms and standards developed over decades or centuries, though they may seem strained today. These gaps reduce players' self-regulation, introduce misunderstandings, and bring about antagonism. Voice chat can worsen power dynamics, leaving many players no choice but to exit. Familiarity and trust lessen the impact of these communication gaps; among strangers, breakdowns are almost inevitable.

Inadequate social tools. Games do a poor job of helping players build connections, experiencing empathy, and fostering trust. Communication by text is unnatural and interrupts gameplay, and there is often little opportunity to clarify intent. Language barriers or differences in communication norms exacerbate these problems.

Verbal communication is not enough. Much of healthy communication is nonverbal. In a game, however, we can neither simply smile at another player nor see the impact of our actions when saying something potentially harmful.

Note: The individual player mechanics that we provide in game serve as digital proxies for body language. They help players communicate nonverbally and instill greater empathy in strangers before engaging more openly in text or chat.[xv]

We don’t get to know one another. Players struggle with empathy if they cannot relate to one another. Games are rarely designed for repeat encounters so players have a chance to become acquainted. If you want to play with someone again, the only option is to “friend” them, but you’ve only just met and in the first stages of building trust. Furthermore, it adds noise to your friends list, which becomes a messy combination of friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

Trust is key. Games push players past their trust limits by putting them in battles and competitions, where a mistake can negatively impact someone they’ve only just met. In general, interactions quickly degrade to antagonism with minimal to no provocation without the benefit of trust to encourage charitable interactions.

Inadequate tools for addressing problems. The lack of tools to respond to uncomfortable situations, such as reporting or shields against further abuse, can generate tacit acceptance of disruptive or harmful conduct. Bystanders can become unintentionally complicit when they do not have a sense of agency or feel pressure not to intervene. If disruptive behaviour is normalised, a player is less likely to stand up to a perpetrator for fear of becoming a target.

Anonymity and social consequences. When players do not face social consequences, they are less apt to feel inhibited in behaving poorly. Anonymity can cause players to wrongly assume similarities or shared views within their immediate group, exacerbate a lack of empathy, and devalue individualism.

Other Factors/Forces

Intent. Understanding why a player thought what they were doing was acceptable can help identify and reduce avenues that support antisocial or antagonistic play patterns. Reasons include:

- Lack of awareness related to cultural differences or immaturity.

- Trolling (expressing antisocial ideology or emulating others who are doing so).

- Conformity.

- Unconscious habits absorbed from community norms or echoing the game itself, such as repeating character voice lines.

- Retaliation, such as “griefing for revenge,” or players believe that they must take matters into their own hands.

High exposure. Whether desired or unwanted, notoriety can be a source of disruptive behaviour, affecting not only the players themselves but their followers and gaming communities.

Note: We should be careful drawing attention to players and influencers. Despite good intentions, we can cause harm by directing unexpected or unwanted attention to streamers, for example. Ideally, we should seek streamers' permission when calling attention to them.

Indirect exposure/privacy. Players find themselves harassed by players able to look up their play statistics or other information. Third party sites scrape data or have access to company-provided APIs and expose player information.

Exposing software specifics. Exposing the granular details of behaviour software, such as penalty systems, can invite players to test the limits of what the software can handle, and can lead to players weaponizing such systems to harass others or creating automated systems for scaled attacks.

Other biases. There can be other biases within a game ecosystem that we may not be aware of. For example, less experienced or new players can tend to attract more blame as their actions stand out more, or it can simply be assumed that they’re the ones “making mistakes.”

Evolutionary/normalising behaviours. Expressions in game evolve. Sometimes this can reduce or eliminate the source of harm or signal the behaviour has become deeply ingrained as part of the culture—consider the evolution from “kill yourself” to “KYS.”

Punishing players we seek to protect. We can inadvertently make things harder for players who are suffering the consequences of disruptive or harmful conduct. Systems that penalise players for leaving a game or dropping out of matchmaking can unfairly punish them and send the wrong message that a game is more important than their well-being.

Blanket restrictions. Words that appear to merit restrictions have broader consequences for individual players and subgroups. A word filter is the lowest common denominator for moderation—a restricted word might be an essential way for players with a particular marginalised identity to relate to each other. Banning an otherwise appropriate word like “gay” to address its abuse in user names constructed to harm or harass is one such instance. Universal restriction of such a term to protect against abuse cases burdens that subgroup.

Education. How we teach children to behave and the examples we set for them significantly affect our ability to coexist in digital spaces. Young people must be encouraged to show respect and compassion toward others, manage their frustrations, and value teamwork in online games while being given a safe space to talk about what they encounter online.

What We Don’t Know

How do we best use this information? What’s next?

Whether we ask the right questions to build features and assess their efficacy presents some of the most challenging work we face as developers. Understanding the root causes of conduct allows us to refine our approaches to designing games and address behaviour within our games and society.

Part 3: What Do We Do About Harmful Conduct?

Using the Framework, we can now focus on systematically addressing disruptive behaviour. Thanks to many developers and researchers, there is a growing collection of knowledge and techniques for developing games that foster healthier interactions. In addition to highlighting that work, this section marks the beginning of a series of resources that help developers confront the issues called out in the Framework.

If you or your studio would be interested in contributing to future versions of these resources, would like help getting started, or have questions on applying these resources, please contact info@fairplayalliance.org, or visit our website for more information.

What Does “Good” Look Like?

People will convey their beliefs whether shared or welcome and they will test limits, so tempers inevitably flare. We cannot entirely eliminate the “human condition” from games because they are digital expressions of society. We cannot entirely eliminate the “human condition” from games because they are digital expressions of society. The real goal is to create spaces better suited to how players interact while taking a strong stance against harmful conduct.

Over time we all evolve different ways of interacting within a gaming community and among our friends to gain a sense of belonging and forge connections with others. Friends and colleagues use banter to bond, but it might be insulting or disempowering for strangers as the banter can interfere with the game's spirit. How do we build inclusive spaces and permit players to express themselves not at the expense of others? How do we stop the bad actor who arrives with the intent to destroy players' positive experiences?

Developers do not want to make all games appropriate for all ages by reducing the variety of content or insisting that all players should somehow get along. What "good" looks like are games and ecosystems that allow players to co-exist more successfully. Getting here is where our work truly begins.

Where we go next

Understanding and addressing disruptive conduct is a natural part of what it means to make a multiplayer game. We can neither put off attending to the problem of disruptive behaviour until we ship, nor can we provide quick fixes and move on. Rather, we must continue to invest in assessment and intervention during the lifetime of a game, from conception to sunset.

We now see the impacts all around of not taking a proactive and human-centric approach to crafting digital spaces more broadly. We have an opportunity to create a better future for gaming spaces, but it will take a concentrated and collaborative effort across the industry beyond what we have done so far if we are to do so.

With the creation and release of this Framework, there are some clear next steps as an industry:

- Develop reliable measures of disruption and community health and share this methodology:

- Assess the conditions within our gaming communities and play spaces: How often does disruptive and harmful conduct occur? In what forms? Who is affected, and how?

- How do we increase transparency and accountability across the industry? How do we share our efforts and outcomes with players and other interested groups? How are we performing as an industry?

- Invest in best practices regarding prosocial design that fosters empathy, trust, connection, and well-being within games.

- Work more closely with game researchers to study the impact and implications of disruptive and harmful conduct, develop better measures, and unlock future opportunities.

- Celebrate the best examples of the values we want to see in games and promote underrepresented voices.

- Finally, explore how to ensure the next generation of gamers thrives in future online communities.

Metrics and Assessment: Getting to a Methodology

The industry lacks transparency when it comes to measuring disruptive behaviour and harmful conduct. One reason is the lack of clarity on how these issues manifest, which this Framework will hopefully illuminate.