Getty Images

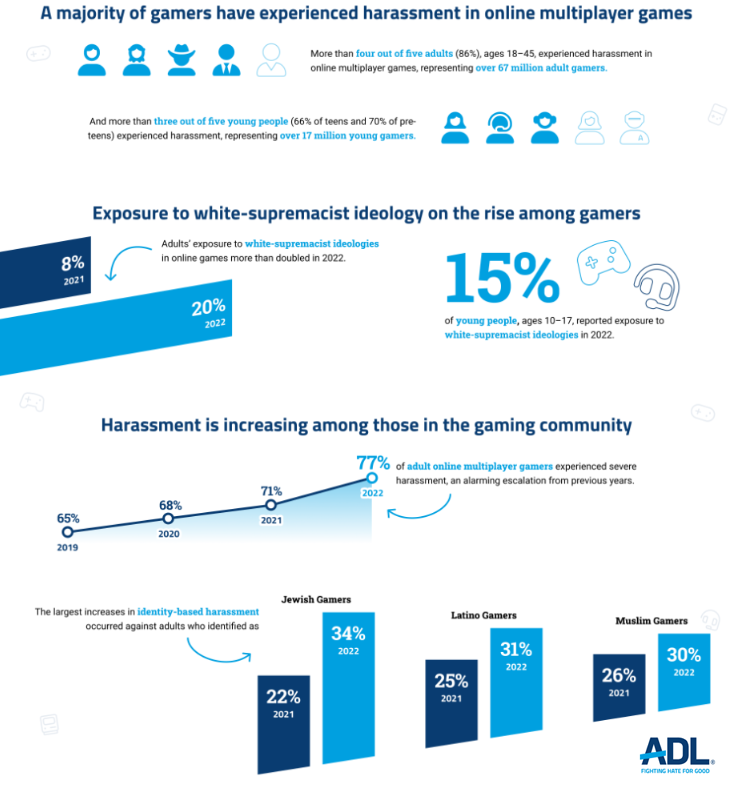

In 2021, ADL found that nearly one in ten gamers between ages 13 and 17 had been exposed to white-supremacist ideology and themes in online multiplayer games. An estimated 2.3 million teens were exposed to white-supremacist ideology in multiplayer games like Roblox, World of Warcraft, Fortnite, Apex Legends, League of Legends, Madden NFL, Overwatch, and Call of Duty.

Hate and extremism in online games have worsened since last year.

ADL’s annual report on experiences in online multiplayer games shows that the spread of hate, harassment, and extremism in these digital spaces continues to grow unchecked. Our survey explores the social interactions, experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of online multiplayer gamers ages 10 and above nationwide.

For the fourth consecutive year, the already-high rates of harassment experienced by a nationally representative sample of nearly 100 million American adult gamers increased. According to the Entertainment Software Association, 76% of gamers in the United States are over 18.

Harassment experienced by teens ages 13-17 increased from last year. For the first time, ADL has collected data on harassment experienced by pre-teens ages 10-12.

The games industry’s progress is slow even when compared to that of social media companies, which are hardly exemplars of user safety or accountability. Only one major games company, Roblox Corporation, has an explicit, public-facing policy against extremism. Earlier this year, Wildlife Studios, a mobile-games company headquartered in Brazil, produced the first gaming transparency report that shares data on how a company acted against hate and harassment in its online games, followed by Xbox in November 2022. Transparency reports and policies banning the expression of extremist ideologies are the bare minimum required to fight hate in online games.

The immense popularity of online games means it is likely that you or someone close to you has experienced hate and harassment. More than two out of three Americans—over 215 million people of all ages—play video games, including both online and offline games. The video games industry is a $203 billion market, with the North American video game market generating over $54 billion in 2022.

In focusing on online multiplayer games, this report offers concrete guidance for the government, civil society, and industry to take meaningful steps in making those games safer for all users, regardless of their age or identity.

On May 14, 2022, a white supremacist extremist committed a mass murder at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, killing 10 Black shoppers and injuring three others. In the logs of his messages on the social platform Discord, the shooter wrote that a game on Roblox was a key vector in his radicalization.

Excerpt from archived version of the Buffalo shooter’s Discord logs referenced by NBC News journalist Benjamin Goggin.

Our 2022 survey finds that adult exposure to white supremacy in online games has more than doubled to 20% of gamers, up from 8% in 2021. Among young gamers ages 10-17, 15% have been exposed to white supremacist ideologies and themes in online games. Our results and other research suggest that the inability of the games industry to build safe, respectful spaces for their users has made communities within online game platforms so rife with hate that they rival the worst places on the internet, such as the notorious forum 4chan.

Although the connection between video games and violence has been repeatedly disproven, there is a growing body of research examining the connection between the industry’s negligence in moderating hate within online games and the normalization of extremist ideologies. In October 2021, the Extremism and Gaming Research Network was launched, bringing together various efforts to study radicalization and online games, as a result of increased interest in this arena.

Unfortunately, there is plenty of grist for this research.

The government of New Zealand released a report on the anti-Muslim attack in Christchurch that clearly showed how the shooter’s path to radicalization started in online multiplayer games, where he was able to “openly express racist and far right views” without pushback from the community or the platform. Researchers used anonymized German police case files to investigate the influence of online gaming spaces such as Roblox and gaming-adjacent social platforms like Discord in radicalizing two children under 14. One of the children was drawn to World War II recreations on Roblox, where he befriended someone who eventually invited him to join a far-right Discord server with users who wanted to “liberate the country of all Jews and fags.” The study echoed Wired’s reporting on extremist activity in Roblox, which found the platform was a fertile environment for fascism, hosting recreations of mass murders and games with slavery.

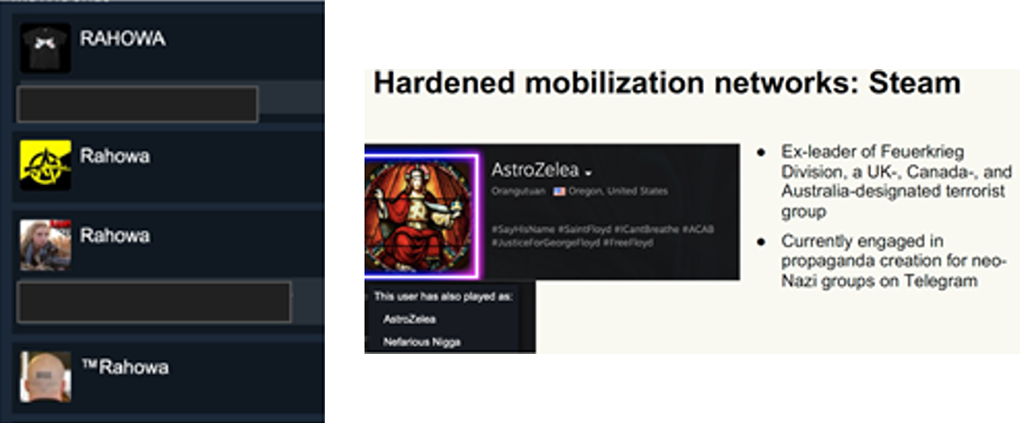

The games industry cannot claim ignorance of disturbing findings related to extremism and online gaming. At the Game Developers Conference (GDC), a major industry event, two researchers, Dr. Rachel Kowert and Alex Newhouse, discussed worrying signs of extremist normalization in the popular game Call of Duty (COD), including the appearance of “RAHOWA,” an acronym for "Racial Holy War” that is used as a rallying cry for white supremacists in usernames on COD’s leaderboards. The researchers also talked about interconnected, openly extremist networks of users on Roblox and Steam, an online games store and forum. They showed the presence of far-right individuals on gaming platforms, including members of the white supremacist group Patriot Front on Roblox and a former leader of the neo-Nazi group Feuerkrieg Division on Steam.

At GDC, Dr. Kowert shared troubling results from her research finding that many people who primarily identified themselves as gamers also strongly agreed with the beliefs of white-nationalist movements. ADL Belfer Fellow Dr. Constance Steinkuehler presented similar results at the Games for Change Festival, another large industry conference. The UN also recently released a report exploring similar connections between extremism, gamers, and online multiplayer games.

Such research is becoming an issue of national security. The Department of Homeland Security awarded a $700,000 grant to Newhouse and Dr. Kowert in September to expand their research into the connection between extremism and online games.

Despite mounting concern, only one major games company, Roblox, prohibits extremism on its platform. Its policy was published only after Roblox faced significant public and private pressure to moderate hateful content and activity discovered on its platform.

In addition to extremism, another form of hate has flourished for years in online games: misogyny. For the fourth year in a row, our survey shows that gender was the most frequently cited reason for identity-based abuse. At Games for Change, Dr. Steinkuehler noted, “In broader national movements, it is typically antisemitism that lies at the root of white supremacy movements; in games, it is misogyny.”

The misogynistic culture of online games is not accidental; one can argue it begins with company culture.

Carlos Rodriguez, the CEO of gaming company G2 Esports, was seen partying alongside noted misogynist Andrew Tate while celebrating the company’s world-championship event. Tate was deplatformed by all mainstream social media companies for repeatedly promoting violence against women and perpetuating rape culture, though he was allowed back on Twitter in November 2022 following Elon Musk’s takeover of the company. Outrage over the event spread online, and Rodriguez initially refused to disavow his association with Tate. After public pressure, Rodriguez apologized, was suspended from running his company for eight weeks, and subsequently stepped down.

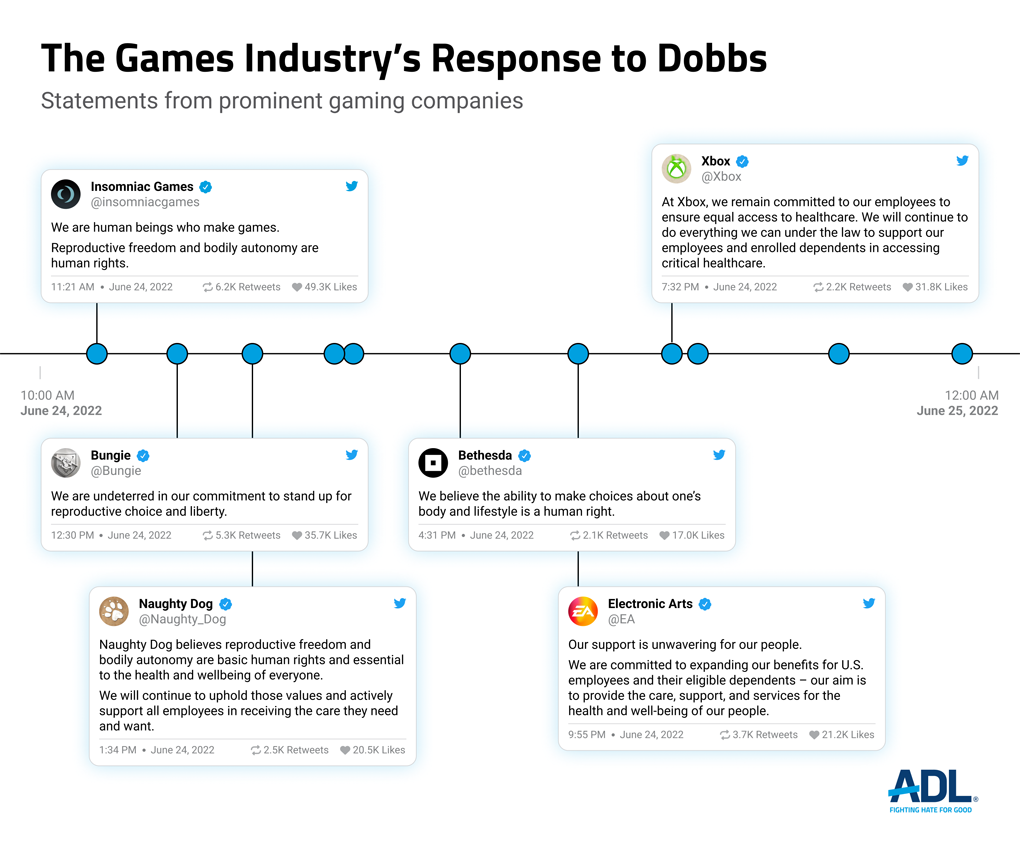

Such an incident points to the glaring hypocrisy of the games industry, where public statements often serve as performative gestures. Misogyny in online games continues unabated, although games companies spoke out against the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade and expressed support for their employees’ right to bodily autonomy. For this year’s survey, we tracked the timeline of public statements by the games industry relative to the gutting of Roe.

Additionally, when asking about various controversial topics related to extremism and disinformation, this year’s survey asked about the degree to which players experienced discussions of anti-abortion extremism and language connected to the “manosphere.” Nearly one in ten adults (7%) were exposed to discussions of these topics that included expressions such as “femoids will pay” or “abortions for black women will help the white birth rate.”

The results of this year’s survey are more dire than ever. The growing investment of civil society, research, and government in examining the relationship between extremism and online games stands in stark contrast to the industry’s refusal to address extremism and misogyny. Extremist activity has grown sharply over the past few years. Democratic institutions are in peril. Thus, all societal actors must act swiftly to stem the tide of hate that afflicts our country.

Hate and Harassment in Online Games

Twenty-five million out of 28 million gamers ages 10-17 in the U.S. play online multiplayer games. Our second year of data on young people ages 13-17 showed a 6% increase in harassment of young people from 60% in 2021 to 66% in 2022. Our first year of data on preteens ages 10-12 shows that nearly three out of four (70%) experience harassment in online games. Overall, 67% of young people ages 10-17 experience harassment in online multiplayer games.

As a result of being targeted by hate in online games, 30% of young players said they always hide their identity when playing online (an increase from 25% last year), while 42% said they sometimes hide their identity, consistent with last year’s results.

Exposure to Extremist White Supremacy

We asked young gamers about their exposure to extremist white-supremacist ideologies in various contexts, including online multiplayer games. Specifically, after explaining to respondents the hateful, racist, and antisemitic nature of these ideologies, we asked if they were exposed to people who “believe that white people are superior to people of other races and that white people should be in charge.”

We found that 15%, or nearly two in ten, young gamers ages 10-17 were exposed to white-supremacist ideologies in the context of online multiplayer games. The other results presented here pertain to young people ages 10-17 who play online games but encountered white-supremacist ideologies in other contexts.

Ally Behaviors

This year we asked young people what actions they or others took when they experienced hate and harassment in online multiplayer games. Most often, they either stood up for themselves or ignored the comment. Least often, other people stood up for the target or reached out to them after they were harassed.

The Impact of Hate and Harassment

The harassment that young people experience in online multiplayer games affects their online and offline lives. Continuing the trend from last year, over a quarter of young people who experienced harassment in online multiplayer games quit specific games.

In-game harassment has offline consequences for young people. One in ten young gamers in the U.S. reported that they treated people worse than usual due to harassment in online gaming, while nearly that many (8%) reported that their school performance declined.

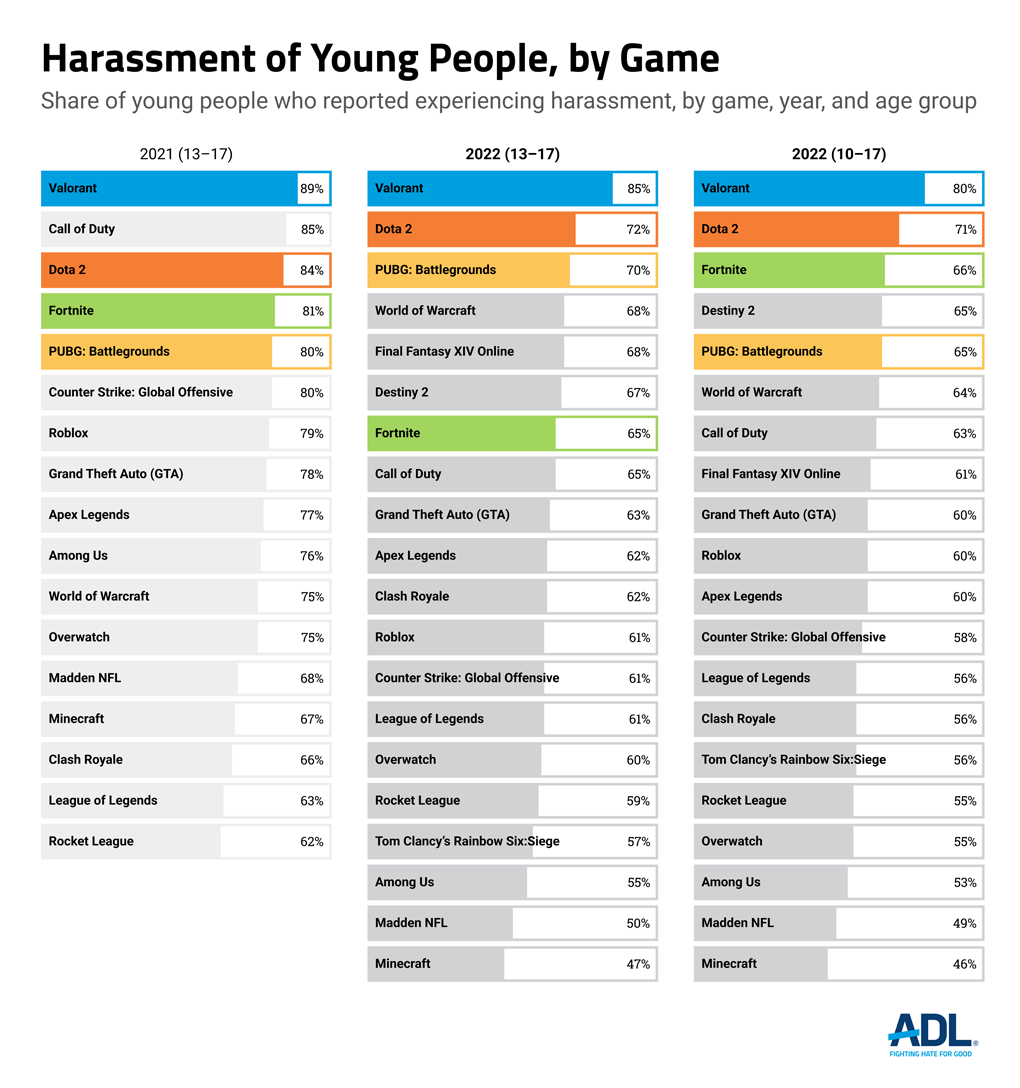

Harassment by Game

At least 47% of young gamers experienced harassment in every game we included in this survey.

Hate and Harassment in Online Games

For the fourth consecutive year, harassment in online games has not decreased. More than four out of five adult gamers experience harassment in online multiplayer games—over 67 million American adults.

Among adult online multiplayer gamers, severe harassment increased from 71% to 77%, with roughly 60 million American adults reporting experiences including physical threats, stalking, and sustained harassment.

For the 2022 study, we continued the methodology of the last two years to collect granular and accurate data regarding swatting and doxing. As in the past, our survey defined “doxing” more broadly than the law does because at present there is no consistent legal standard. In our questions, we provided the following broad definitions of doxing and swatting:

We then asked respondents who experienced either scenario to describe what happened. In our total figures for swatting and doxing, we included the responses of some players who reported something similar to either behavior or preferred not to elaborate. We removed descriptions unrelated to swatting or doxing from our final numbers. Based on this methodology, 17% of respondents were doxed, and 12% were swatted. While the number of gamers that experience swatting remains constant within the margin of error, the number of adult gamers that experience doxing increased by 6%.

“I had my address and personal phone number leaked to a group of players in the game.”

--20-year-old nonbinary Jewish white bisexual gamer

“I had a person take a picture off my post and use it in a game that I was playing. It was sexually humiliating.”

--43-year-old female white disabled heterosexual gamer

“Having weapons drawn on me when the police believe I have a hostage situation is very scary.”

--24-year-old male Asian American Buddhist heterosexual gamer

“It was regular, honestly, playing games and this one dude had told me straight up he was gonna make the call and I didn’t believe him until people were at my door.”

--22-year-old male Latino Muslim disabled heterosexual gamer

Identity or Hate-Based Harassment

Hate-based harassment is defined as disruptive behavior that targets players based at least partly on their actual or perceived identity, including but not limited to their age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, religion, or membership in another protected class.

While identities across the board faced a similar or somewhat increased level of hate in 2022 compared to 2021, the group that experienced the largest year-over-year increase in harassment was Jewish online multiplayer gamers, with a 12% increase from 22% to 34%. In the previous three years of this survey, hate targeting Jewish gamers decreased or remained static, making these results even more troubling.

“I stupidly said I was Jewish and they started the myth jokes.”

--42-year-old Jewish white male heterosexual gamer

“People were saying the holocaust didn’t happen. It was pretty upsetting seeing as my ancestors went through the unfortunate event.”

--21-year-old Jewish white female bisexual gamer

Extremism, Conspiracy Theories, and Disinformation

Our results found that exposure to white-supremacist ideologies in online games has more than doubled in the last year, from 8% of adults in 2021 to 20% of adults in 2022.

It is important to note that within the context of this survey, we are not referring to “white supremacy” as the historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of white dominance and privilege in the U.S., which enables and maintains systemic racism throughout all segments of society. Rather, ADL uses the term “white supremacy” here to specifically refer to the collection of extremist ideologies and groups undergirding the beliefs that white people should dominate in all ways and exercise power over other identities, that there should be a “whites-only” nation, and that “white culture” is expressly superior to other cultures and must be supported at the expense of other cultures. Here, we specify white-supremacist ideology as a symptom and an outgrowth of systematic white supremacy.

Similar to what we found in the past two years of the survey, some descriptions of players’ experiences in online games are consistent with what ADL would call explicit white-supremacist ideologies, while others are hateful experiences that do not refer to the explicit beliefs of white supremacists. Explicit white supremacy:

“I was playing with some random people online and they initiated a conversation about how other races are supposed to be slave's to the supreme white race.”

--20-year-old male white protestant heterosexual disabled gamer, playing Call of Duty

Hateful experience:

“They where calling people n***** and chanting trump 2024.”

--29-year-old male Black or African American gay Protestant gamer, playing Grand Theft Auto

Hate may be motivated by an offending player’s belief in white supremacy or aspects of white-supremacist ideologies, which are antisemitic, anti-Muslim, racist, sexist, and homophobic at their core. But without more information about the motivation behind hateful remarks, it is difficult to be sure. We decided to include such experiences in our tally, deferring to players’ reported experiences of white supremacy. Furthermore, our total included respondents who opted not to share their experiences due to their sensitive nature.

Additionally, our survey asked players about their exposure to disinformation or hate targeting the Asian American community and its alleged connection to COVID-19 as well as disinformation related to the 2020 election. We also asked about antiabortion and extremist misogynist ideologies. Finally, we asked about the prevalence of players’ exposure to conversations about Holocaust denial.

Given the growing concern over the problem of white-supremacist extremism in online gaming, we decided to further expand the questions in our survey around this topic. For the first time, we also asked players to state the specific game in which they had experiences with white-supremacist ideologies. While this method cannot ascertain the scope of the problem with extremism in any of the games we list here, we believe it sufficient to state that experiences of white-supremacist extremist ideologies are not specific to any one genre or game title, much as this survey has found regarding hate and harassment in the past.

The games where players most often encounter extremist white-supremacist ideologies are Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, Valorant, World of Warcraft, Fortnite, and PUBG: Battlegrounds.

Harassment by Game

ADL and Newzoo chose to analyze players’ experiences of harassment in several popular online multiplayer games. The increase in harassment among these titles this year is particularly concerning. In 2021, our survey found that the game where players most often experienced harassment was Valorant, with 79% of players reporting an experience of harassment in that game. In our 2022 survey, more than 80% of players reported experiencing harassment in six of the titles we asked about: Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (86%), Valorant (84%), PUBG: Battlegrounds (83%), Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege (81%), League of Legends (81%), and Call of Duty (80%).

The Impact of Hate and Harassment on Players

Our survey looked at the impact harassment in online games had on players and how their experiences affected their gameplay. The number of players who quit playing specific online multiplayer games because of harassment increased for the fourth consecutive year.

The impact of harassment in online games affects how people play. Out of the 67 million American adults who experience harassment in online multiplayer games, only 19% stated that it had no impact on how they play, meaning that harassment shapes the gameplay of over 54 million American adults.

Ally Behaviors

This year we asked adults what actions they or others took when they experienced hate and harassment in online multiplayer games. The most common actions were that people either stood up for themselves or ignored a comment, while among the least common actions were other people standing up for the target or reaching out to them after being harassed.

Responsibility for Addressing Hate and Harassment in Online Games

As part of our 2022 survey, we asked gamers for their opinions on different statements regarding how to address hate and harassment in online multiplayer games.

We also asked respondents who they felt should be responsible for addressing hate and harassment in online games.

ADL, in collaboration with Newzoo, a data analytics firm focused on games and esports, designed a nationally representative survey to examine Americans’ experiences of disruptive behavior in online multiplayer games. We collected responses from 2,134 Americans who play games across PC, console, and mobile platforms, including 1,931 responses from people who play online multiplayer games. For young people ages 10-17, we also collected responses from their parents or guardians as part of the screening process.

We oversampled individuals who identify as LGBTQ+, Jewish, Muslim, Black or African American, Asian American and Hispanic/Latinx. We collected responses for the oversampled target groups until at least 125 Americans were represented in each group. Surveys were conducted from June 21 to July 7, 2022. The margin of error based on our sample size is generally 2 to 3 percentage points, though this may be slightly higher when looking at smaller sample sizes.

We asked adult respondents ages 18-45 whether and how often they experienced “disruptive behavior” including:

We also asked young people ages 10-17 about their experiences of disruptive behavior but altered the categories slightly. We changed the wording in some cases to focus on disruptive behaviors young people may be most familiar with, and we limited questions about other behaviors to avoid subjecting young participants to additional harm. For example, we did not ask young people about their experiences with threats of physical violence or sexual harassment. We asked teenagers and preteens if they had:

In the analysis provided in this report, we refer to the forms of disruptive behavior experienced by adults or young people, as described above, as harassment.

Harassment by Delivery Channel

Our survey also examined the delivery channels within online games where young people reported experiencing harassment.

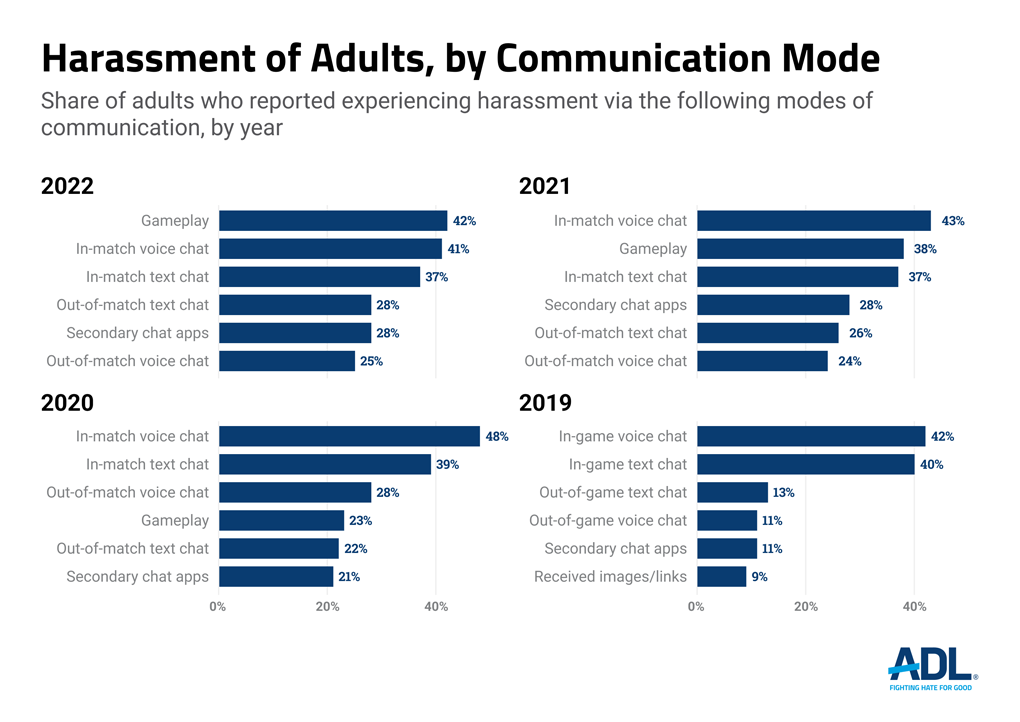

Harassment by Delivery Channel

To learn more about the environments in which online multiplayer gamers experienced harassment, we asked players about the delivery channels they used. More players reported harassment through voice chats than text chats for both in-game and out-of-game channels.

This work is made possible in part by the generous support of:

Anonymous

The Robert Belfer Family

Dr. Georgette Bennett and Dr. Leonard Polonsky

Craig Newmark Philanthropies

Electronic Arts

Joyce and Howard Greene

Hess Foundation, Inc.

Modulate

Righteous Persons Foundation

The David Tepper Charitable Foundation, Inc.