Related Content

Online Hate and Harassment: The American Experience 2021

Executive Summary

How safe are social media platforms now? Throughout 2020 and early 2021, major technology companies announced that they were taking unprecedented action against the hate speech, harassment, misinformation and conspiracy theories that had long flourished on their platforms.

According to the latest results from ADL’s annual survey of hate and harassment on social media, despite the seeming blitz of self-regulation from technology companies, the level of online hate and harassment reported by users barely shifted when compared to reports from a year ago.

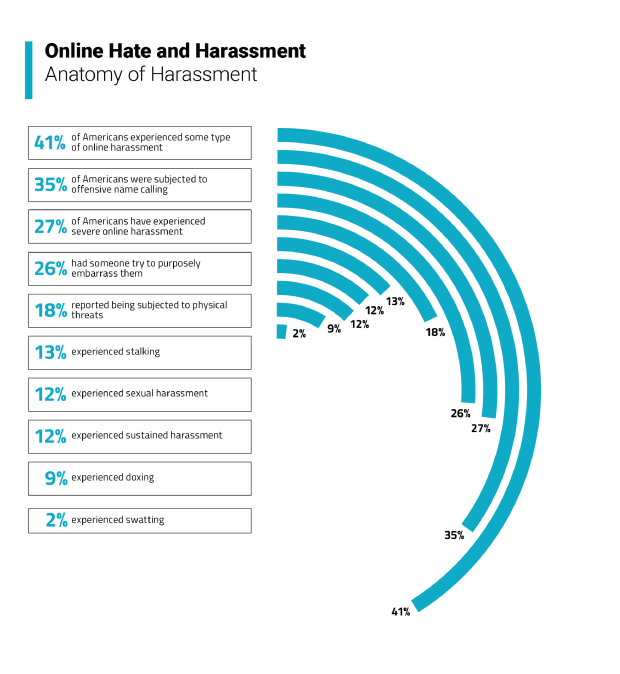

This is the third consecutive year ADL has conducted its nationally representative survey. Forty-one percent of Americans who responded to the survey said they had experienced online harassment in this year’s survey, comparable to the 44% reported in ADL’s 2020 “Online Hate and Harassment” report. Severe online harassment comprising sexual harassment, stalking, physical threats, swatting, doxing and sustained harassment also remained relatively constant compared to the prior year, experienced by 27% of respondents, not a significant change from the 28% reported in the previous survey.

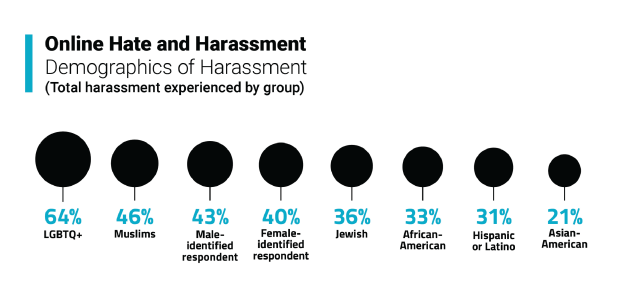

- LGBTQ+ respondents reported higher rates of overall harassment than all other demographics for the third consecutive year, at 64%.

- 36% of Jewish respondents experienced online harassment, comparable to 33% the previous year.

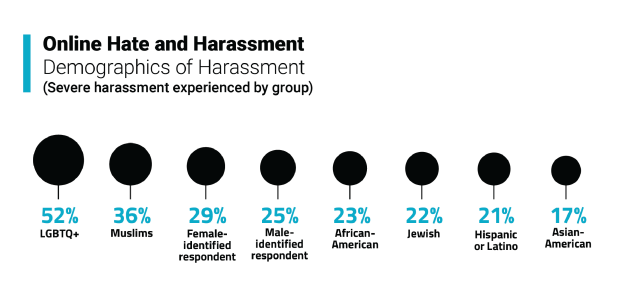

- Asian-American respondents have experienced the largest single year-over-year rise in severe online harassment in comparison to other groups, with 17% reporting it this year compared to 11% last year.

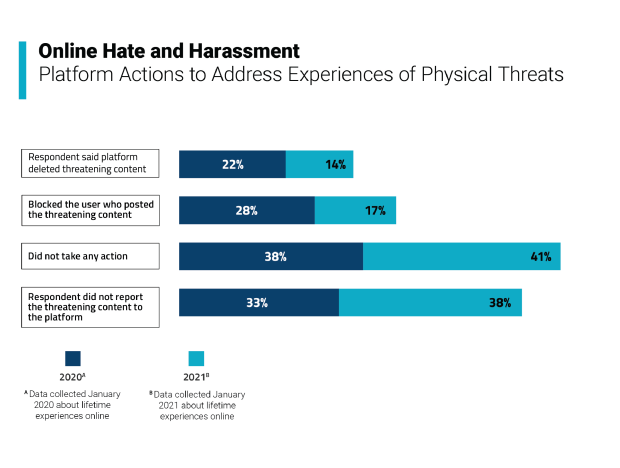

This year, fewer respondents who experienced physical threats reported them to social media platforms than was the case the year before; these users also reported that platforms were doing less to address their safety.

- 41% of respondents who experienced a physical threat stated that the platform took no action on a threatening post, an increase from the 38% who had reported a similar lack of action the year before.

- 38% said they did not flag the threatening post to the platform, up from 33% the prior year.

- Only 14% of those who experienced a physical threat said the platform deleted the threatening content, a significant drop from 22% the prior year.

- Just 17% of those who experienced a physical threat to the platform stated that the platform blocked the perpetrator who posted the content, a sharp decrease from the prior year’s 28%.

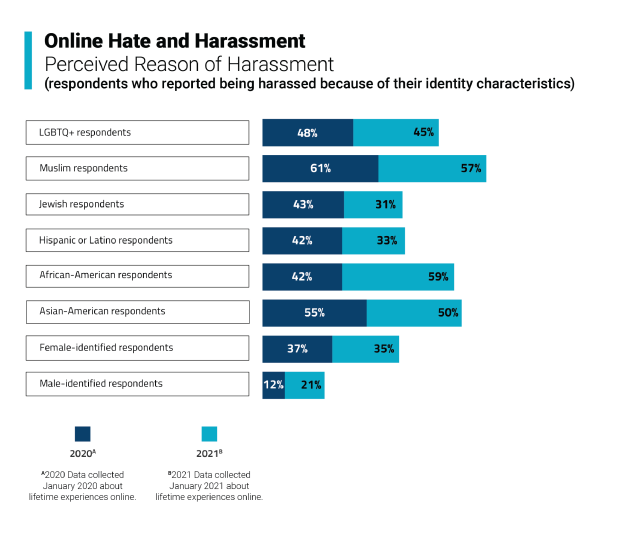

The percentage of respondents who reported being harassed because of their identity[i] was comparable to the previous year.

- 33% of survey respondents reported identity-based harassment this year, not a statistically significant change from 35% last year.

- 28% of survey respondents reported race-based harassment, comparable to 25% recorded a year ago.

- However, African-American respondents reported a sharp rise in race-based harassment, from 42% last year to 59% this year.

There was a relatively small drop in perceived religion-based harassment reported by Muslim respondents from 61% last year to 57% this year. Likewise, Asian-American respondents reported a relatively small decrease in online race-based harassment this year (50% from 55%). Regardless, these levels of harassment remain disturbingly high.

Critics, including ADL, contend that platforms instituted their policy changes after years of ignoring warnings about the rise of misinformation and violent rhetoric.[ii] Encountering hate and harassment online has become a common experience for millions of Americans—and that experience does not appear to be getting safer. Technology companies are not resourcing to handle the magnitude of the problem, regardless of what their public-facing statements say to the contrary.

Introduction

This report’s findings follow a tumultuous period of social unrest. As of March 19, official records report over 535,000 [iii] American deaths from the Covid-19 virus, and accompanying illness and financial catastrophe for many millions more. The May 25, 2020 murder of George Floyd by police officers sparked a wave of massive racial justice protests in which somewhere between 15 and 26 million Americans participated over the next several months—perhaps the largest movement ever in U.S. history.[iv] A long and bitter election cycle further sundered what was already a deeply divided country. For the only time in American history, a president obstructed the peaceful transition of power. [v] And for the first time since 1814, the U.S. Capitol was breached.

Online Hate Speech Moves Offline

Even before the pandemic caused much of daily life to move online for untold numbers of Americans, there was mounting concern over social media abuses and the monopolistic levels of power exercised by the big technology companies, chiefly Facebook, Twitter, and Google, which owns the YouTube platform. These three companies have a large influence over the rules governing online speech for billions of people and incredible power over the experience of vulnerable and marginalized people online. Under their watch, online speech has become rife with hate content, conspiracy theories, and misinformation.

For the past year, ADL has documented the damaging effect hateful content online has on communities.

- The spike in physical violence against Asian-Americans across the nation was whipped up in large part by bigotry and conspiracy theories that grew online, fanned by national leaders, including former President Trump’s incendiary rhetoric blaming China for the pandemic and referring to the virus as the “China plague” or “kung flu.” [vi] ADL researchers saw an 85 percent increase in negative sentiment on Twitter towards Asians following news that he contracted the coronavirus. [vii]

- In October, ADL reported that in the months preceding the 2020 presidential election, Jewish members of Congress faced antisemitic attacks on Twitter, often in the form of conspiracy theories claiming that Jewish people control world governments, the banking system, media and much else.[viii]

- Derogatory posts against African-Americans quadrupled on Facebook pages shortly after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and during the start of Black Lives Matter protests across the country. They stayed elevated until September, when the pace of protests slowed.[ix]

Under the mounting public pressure channeled by advocacy campaigns like Stop Hate for Profit, technology companies instituted a wave of policy and product changes on their platforms. Facebook prohibited Holocaust denial content[x] after years of outcry from ADL and other civil society organizations.[xi] The company took numerous steps to mollify civil rights organizations: it hired a vice president of civil rights;[xii] changed parts of its advertising platform to prohibit various forms of discrimination; expanded policies against content that undermined the legitimacy of the election; and built a team to study and eliminate bias in artificial intelligence.[xiii] Due to pressure from ADL and other civil rights organizations, Twitter banned linked content, URL links to content outside the platform that promotes violence and hateful conduct,[xiv] which led to the permanent banning of former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke for repeatedly violating the company’s hateful conduct policy.[xv] Reddit added its first global hate policy, providing for the removal of subreddits and users that “promote hate based on identity or vulnerability.” As part of this crackdown on hate content, the platform banned 2,000 subreddits—community message boards—including the r/The_Donald subreddit.[xvi] In a move that proved prescient, on June 29, 2020, the livestreaming site Twitch, owned by Amazon, temporarily suspended former President Donald Trump’s channel for hateful conduct after it rebroadcast a video from a 2016 campaign rally where Trump said Mexico was sending criminals to the United States.[xvii]

Twitch’s decision anticipated the decisions later made by Facebook, Twitter,[xviii] and YouTube[xix] to deplatform Trump for using his accounts to share false information and inciting his voter base to violence in the wake of the insurrection at the Capitol. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg posted a statement on the platform explaining the rationale behind this removal:

“Over the last several years, we have allowed President Trump to use our platform consistent with our own rules, at times removing content or labeling his posts when they violate our policies...But the current context is now fundamentally different, involving use of our platform to incite violent insurrection against a democratically elected government. We believe the risks of allowing the President to continue to use our service during this period are simply too great.”[xx]

Technology companies made possible this firehose of hate speech, conspiracy theories, and misinformation through news feeds powered by algorithms that amplified divisive and false content, which in turn kept users on their platforms longer, thereby driving revenue.[xxi] Research has long shown that people tend to spread false information at higher and faster rates than factual information.[xxii] Algorithms feed users tailored content based on their browsing activity and if a user has viewed hateful content or is looking for it, algorithms will serve up more of the same—or worse.

In the case of Facebook, its artificial intelligence engineers tried to reduce polarization by tweaking the platform’s algorithms but their work was reportedly deprioritized when it hindered the company’s goal of maximizing user engagement. Users are drawn to controversial, outrageous content so limiting its spread runs counter to Facebook’s reported ambitions for growth.[xxiii]

Black Boxes

Despite extensive public documentation of their failings, technology companies have for years tried to prove they can oversee themselves. Most of the steps taken came only after intense public pressure and the threat of legislative action. Twitter, for example, banned political advertisements. Facebook created an Oversight Board, a group currently numbering about 20 journalists, politicians and judges, to serve as a quasi-judiciary body to make decisions only on appeals to the platform’s content moderation decisions. This is far too limited a remit. [xxiv] The Board is currently deciding whether to allow the former president back on its platforms.

The big companies remain black boxes regarding transparency. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey admitted in a January 13 tweet that his company fell short on its trust and safety measures: “Yes, we all need to look critically at inconsistencies of our policy and enforcement. Yes, we need to look at how our service might incentivize distraction and harm. Yes, we need more transparency in our moderation operations.”[xxv]

Hiring thousands of content moderators and training artificial intelligence software to remove online hate speech have not worked so far to make social media respectful and inclusive digital spaces. Automated moderation often does not accurately interpret the meaning and intent of social media posts while human moderators often miss important cultural cues and context. Absent comprehensive audits disclosing the working and the impact of algorithms that decides what users see, the public has only a vague idea of how much hateful content exists on platforms and how effective companies really are in enforcing their guidelines, including by removing or otherwise mitigating egregious content.

Methodology

A survey of 2,251 individuals was conducted on behalf of ADL by YouGov, a leading public opinion and data analytics firm, examining Americans’ experiences with and views of online hate and harassment. A total of 847 completed surveys were collected to form a nationally representative base of Americans 18 years of age and older, with additional oversamples from individuals who self-identified as Jewish, Muslim, African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic or Latino, or LGBTQ+. We oversampled the Jewish population until at least 500 Jewish Americans responded. For other oversampled target groups, responses were collected until at least 200 Americans were represented from each of those groups. Data was weighted on the basis of age, gender identity, race, census region, and education to adjust for national representation. YouGov surveys are taken independently online by a prescreened set of panelists representing many demographic categories. Panelists are weighted for statistical relevance to national demographics. Participants are rewarded for general participation in YouGov surveys but were not directly rewarded by ADL for their participation in this survey. Surveys were conducted from January 7, 2021, to January 15, 2021. Data for ADL’s online harassment surveys was collected in December 2018, January 2020, and January 2021.

The surveys asked about respondents’ lifetime experiences online. The margin of sampling error for the full sample of respondents is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points. Unless otherwise noted, year-over-year differences are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level or higher.

Results

Who Is Harassed?

Although technology companies insist they have taken robust action to address users’ safety and remove harmful content throughout the past year, this report finds scant difference in the number of Americans who experienced online hate and harassment.

The survey finds that online harassment remains a common feature of many Americans’ lives. This year, 41% of Americans who responded to our survey said that they had experienced online harassment over the past twelve months. This statistic is comparable to the 44% reported in the previous year’s “Online Hate and Harassment” report. Moreover, LGBTQ+ respondents in particular continued to report disproportionately higher rates of harassment than all other identity groups at 64%, no significant change from the 65% in the previous survey. Following them are Muslim respondents, at 46%, not a statistically significant difference from the already high 42% who reported experiencing harassment during the previous year.

More than a quarter of respondents, 27%, experienced severe online harassment over the past year, which includes sexual harassment, stalking, physical threats, swatting, doxing, and sustained harassment.

With the exception of Hispanic or Latino respondents (the survey listed “Hispanic or Latino” identity as a single ethnic category), the amount of severe harassment experienced by groups did not change much. As was the case with overall reports of harassment, LGBTQ+ respondents, at 52%, experienced far higher rates of severe harassment than all other groups. The next highest amount of severe harassment reported was from Muslim Americans, at 36%, comparable to 32% previously. Severe harassment among female-identified respondents stayed relatively stable compared to the prior year, at 29%. Notably in a year of coronavirus-related bigotry and surging physical attacks, the biggest jump in severe harassment was reported by Asian-Americans, at 17%, compared to 11% reported a year ago. Hispanic or Latino respondents had the largest drop in experiences of severe harassment, from 28% to 21%.

Simultaneously, as the incidence of severe harassment did not lessen, respondents reported that platforms did less to address physical threats. Forty-one percent of respondents stated that social media platforms did not take any action on the threatening content, not statistically significant from the 38% reported last year. Over a third of respondents, 38%, did not report the content in question to the platform, comparable to 33% last year. Only 14% of those surveyed reported that the company deleted the threatening content, a significant drop from 22% a year ago. Lastly, 17% stated the platform blocked the user who posted the threatening content, a sharp decrease from last year’s result of 28%.

These results raise questions about why targets of online harassment may choose not to use reporting features on social media platforms, even when faced with threats of physical violence, and whether technology companies are doing enough to keep users safe.

Why Are Targets Harassed?

The survey asked respondents to report whether they were harassed and whether they thought they were harassed because of their identity—their sexual orientation, religion, race or ethnicity, gender identity, or disability. Sexual and religious minorities, as well as people who identify as female and Asian-Americans are justified in their concerns of being harassed online, not to mention their physical safety.

Similar to our findings last year, one in three respondents reported that the harassment they experienced was tied to their identity. Identity-based harassment remains worrisome, affecting the ability of already marginalized communities to be safe in digital spaces. Muslim Americans, African-Americans and Asian-Americans continued to face especially high rates of identity-based bigotry and harassment. Fully 59% of African-Americans reported they were harassed online because of their race in this year’s survey, a sharp increase from 42% last year. There was no statistically significant change in race-based harassment overall, 28% this year from 25% last year. Harassment based on religion did not change, remaining at 21%.

- Respondents said they were targeted as a result of their occupation (14%), disability (12%), or sexual orientation (10%).

- 31% of Jewish respondents reported they felt they were targeted with hateful content because of their religion, a notable decrease from 43% reported last year.

- 45% LGBTQ+ respondents reported harassment based on their sexual orientation, comparable to the 48% reported last year. The percentages are still dismayingly high.

- Women also experienced harassment disproportionately, as 35% of female-identified respondents felt they were targeted because of their gender, no significant change from last year’s survey (37%).

- Nearly half (49%) of all who reported being harassed believed that their political views drove at least part of the harassment, a decrease compared to 55% the previous year.

- 33% of respondents reported harassment due to their physical appearance, not a significant change from the 35% reported last year.

How Are Targets Impacted?

The most prevalent forms of harassment were generally isolated incidents: 35% of respondents were subjected to offensive name-calling, and 26% had someone try to purposely embarrass them. But more severe forms of harassment were also common—27% of American adults reported such an experience, essentially flat to the 28% reported from last year. We defined “severe harassment” as including sexual harassment, stalking, physical threats, swatting, doxing, and sustained harassment.

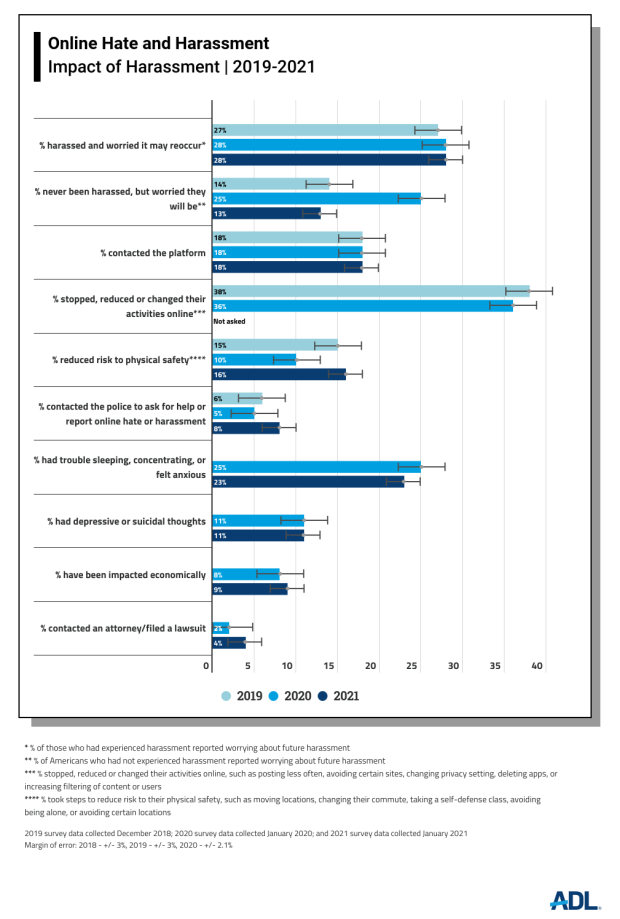

Many respondents who were targeted or feared being targeted with hateful or harassing content reported being affected in terms of their economic, emotional, physical, and psychological well-being.

At 23%, a significant number of respondents reported having trouble sleeping, concentrating, and feeling anxiety. Despite reports that fewer platforms took action when harassment was reported, nearly a fifth of harassment targets (18%) contacted the platform to ask for help or report harassing content. Another 16% of respondents took steps to reduce risk to their physical safety that included moving locations, changing their commute, taking a self-defense class, avoiding being alone, or avoiding certain locations. In some cases, these behaviors were coupled with other impacts, including thoughts of depression and suicide, anxiety, and economic impact. Eight percent contacted the police to ask for help or to report online hate and harassment, comparable to 5% a year ago.

- 13% of respondents experienced stalking.

- 12% of respondents were targets of sexual harassment.

- 12% of respondents experienced sustained harassment.

- 11% of respondents had depressive or suicidal thoughts as a result of their experience with online hate.

- 9% of respondents reported experiencing adverse economic impact as a result of online harassment.

- Only 4% contacted an attorney or filed a lawsuit.

One consequence of widespread online hate and harassment is that it leaves people worried about being targeted in the future: 29% of those who had previously experienced harassment and 13% of Americans who had not experienced harassment reported worrying about future harassment.

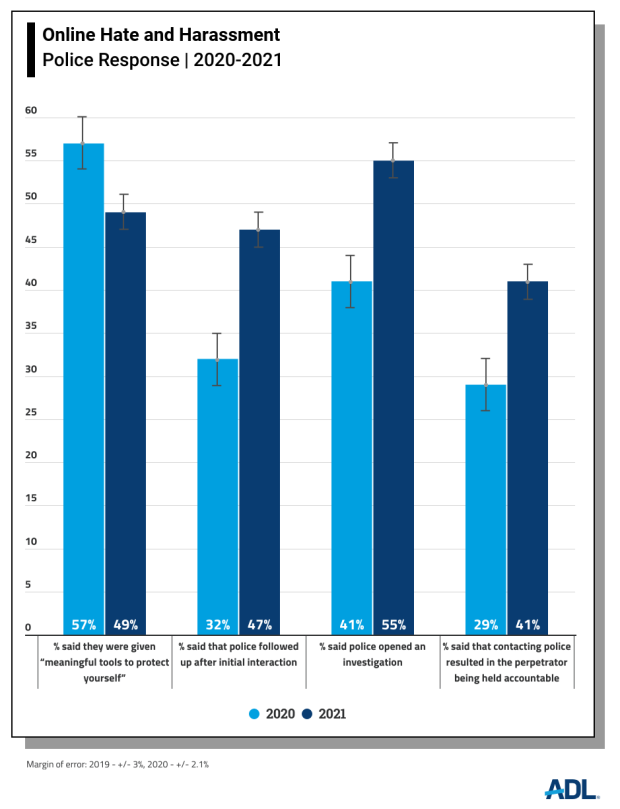

Of the respondents who contacted the police (8%), 49% stated that they were given meaningful tools to protect themselves, not a statistically significant change from 57% last year.

Where Are Targets Harassed Online?

The survey also asked about where hate and harassment had occurred online. Facebook, the largest social media platform in the world, was implicated in the highest percentage of online harassment reports, with three-quarters (75%) of those who experienced online harassment reporting that at least some of that harassment occurred on Facebook. Smaller shares experienced harassment or hate on Twitter (24%), YouTube (21%), Instagram (24%), WhatsApp (11%), Reddit (9%), Snapchat (15%), Discord (7%) and Twitch (6%). (Note: YouTube is owned by Google; Instagram and WhatsApp are both owned by Facebook; Twitch is owned by Amazon.)

Note that the results may underestimate the amount of harassment on the platforms because some targets may have since stopped using a platform for reasons either related or unrelated to the harassment.

What Solutions Do Americans Want?

Given the enormous numbers who experience hate and harassment online, it is probably unsurprising that Americans overwhelmingly want platforms, law enforcement agencies and policymakers to do more to address the problem. Both targets of harassment and those who did not report having been harassed want effective action by platforms and more legal accountability. This suggests that the problem is not only widespread, but recognized to be a serious issue requiring action. Support is strong for these recommendations across the political-ideological spectrum.

- 81% of Americans agree social media platforms should do more to counter hate online.

- 78% of Americans want platforms to make it easier to report hateful content and behavior.

- 80% want companies to label comments and posts that appear to come from automated “bots” rather than people.

- 80% of Americans agree with the statement that police should have more training and resources to help people with online hate and harassment.

- 81% agree that laws should be strengthened to hold perpetrators of online hate accountable for their conduct.

There is also a significant interest in greater transparency from social media platforms, higher than reported in the last survey. Americans want a clearer picture of the scope of online hate and harassment than that which social media platforms typically provide. They want higher degrees of accountability and transparency. Users also want to understand which communities are affected by online hate.

- 77% of respondents want platforms to provide greater transparency on how their algorithms order, rank, and recommend content.

- 72% of respondents to the survey want platforms to report on the incidence of hate for different communities in their transparency reports (for example, report the number of pieces of content removed for anti-LGBTQ+, antisemitism, anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant hate). This is a significant increase in a number that was high even a year ago, at 64%.

- 69% of respondents want platforms to have outside experts and academics independently report and research on the amount of hate on their platform.

An overwhelming majority of respondents (78%) want platforms to give users more control over their online space by providing them with more sophisticated blocking features such as IP blocking, which involves blocking the identity of certain addresses from accessing their services. Finally, a large percentage of respondents (74%) also want platforms to remove problematic users.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has underscored many long-existing fissures within American society and one of them is the potential of social media platforms to cause great harm. With people spending even more time online during this fraught time, it has never been clearer that while the internet connects people in ways we could not have imagined just 25 years ago, it also sows hate, harassment and violence, often at warp speed. The people most affected by conspiracy theories, hate speech and misinformation online tend to be those who live with it offline, people who have historically faced heightened levels of discrimination and bigotry. These users do not feel safe online. This survey shows that the widespread abuse on social media platforms intensifies their struggles.

Big technology companies have taken only piecemeal approaches to solving the problems of hate and harassment on their platforms because their business models thrive off them. The more hate that exists on a platform, the longer users stay, and the higher the advertising dollars. Substantive regulation may be finally coming and for people of color, religious and sexual minorities, and women, it is overdue.

Recommendations

This report's findings show that the vast majority of the American public — across demographics, political ideology and experience with online harassment — want both government and private technology companies to take more action against online hate and harassment.

For Technology Companies

This survey highlights a consistent demand by users (81% of respondents) for technology companies to do more to counter online hate and harassment. An overwhelming majority of respondents also agree with recommendations for increased user control of their online space (78%), improved tools for reporting or flagging hateful content (78%), increased transparency (77%), and accountability in the form of independent reports (69%).

a. Ensure strong policies against hate

As a baseline, technology companies should ensure that their social media platforms have community guidelines or standards that comprehensively address hateful content and harassing behavior, and clearly define consequences for violations. This should be the standard for all platforms active or launching in 2021 and beyond. While some platforms have comprehensive policies at present, not all do. Platforms that do not have robust policies show indifference to addressing the harms suffered by vulnerable and marginalized communities.

b. Enforce policies equitably and at scale

Technology companies must regularly evaluate how product features and policy enforcement on their social media platforms fuel discrimination, bias, and hate and make product/policy improvements based on these evaluations. When something goes wrong on a major social media platform, tech companies blame scale. Millions, even billions, of pieces of content can be uploaded worldwide, shared, viewed and commented upon by millions of viewers in a matter of seconds. This massive scale serves as the justification for “mistakes” in content moderation, even if those mistakes result in violence and death. But scale is not the primary problem—defective policies, bad products and subpar enforcement are. When it comes to enforcement, platforms too often miss something, intentionally refrain from applying the rules for certain users (like elected officials), or have biased algorithms and human moderators who do not equitably apply community guidelines. Companies should also create and maintain diverse teams to mitigate bias when designing consumer products and services, drafting policies, and making content moderation decisions.

c. Design to reduce the influence and impact of hate

Technology companies should put people over profit by redesigning their social media platforms and adjusting their algorithms to reduce the impact of hate and harassment. Currently, most platform algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement to keep users logged on for as long as possible to generate advertising revenue. Too often, those algorithms recommend inflammatory content. Questionable content shared by users who have been flagged multiple times should not appear on news feeds and home pages even if the result is decreased.

d. Expand tools and services for targets of harassment

Given the prevalence of online hate and harassment, technology companies should ensure their social media platforms offer far more services and tools for individuals facing or fearing an online attack. Social media platforms should provide effective, expeditious resources and redress for victims of hate and harassment. For example, users should be allowed to flag multiple pieces of content within one report instead of creating a new report for each piece of content. They should be able to block multiple perpetrators of online harassment at once instead of undergoing the laborious process of blocking them individually. IP blocking, preventing users who repeatedly engage in hate and harassment from accessing a platform even if they create a new profile, helps protect victims.

e. Improve transparency and increase oversight

Technology companies must produce regular transparency reports and submit to regularly scheduled external, independent audits so that the public knows the extent of hate and harassment on their platforms. Transparency reports should include data from user-generated, identity-based reporting. For example, if users report they were targeted because they were Jewish, that can then be aggregated to become a subjective measure of the scale and nature of antisemitic content on a platform. This metric would be useful to researchers and practitioners developing solutions to these problems. In addition to transparency about policies and content moderation, companies can increase transparency related to their products. At present, technology companies have little to no transparency in terms of how they build, improve and fix the products embedded into their platforms to address hate and harassment. In addition to transparency reports, technology companies should allow third-party audits of their work on content moderation on their platforms. Audits would also allow the public to verify that the company followed through on its stated actions and to assess the effectiveness of company efforts across time.

For Government

A large portion of survey respondents agreed that the government has an important role in reducing online hate and harassment. Eighty percent of Americans agree there should be more police training and resources to help people with online hate and harassment. And an overwhelming majority of respondents agree that laws should be strengthened to hold perpetrators of online hate accountable for their conduct (81%). Further, officials at all levels of government can use their bully pulpits to call for better enforcement of technology companies' policies.

Government can address online hate and harassment through legislation, training, and research:

a. Prioritize regulations and reform

Platforms play an active role by providing the means for transmitting hateful content and, more passively, enabling the incitement of violence, political polarization, spreading of conspiracies, and facilitation of discrimination and harassment. Unlike traditional publishers, technology companies are largely shielded from legal liability due to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA 230). There is a lack of other legislative or regulatory requirements even when companies’ products, actions or omissions may aid and abet egregious civil rights abuses and criminal activity. Oversight and independent verification of the claims technology companies make in their transparency reports and related communications are not in place because there are no independent audits of their internal systems.

Governments must carefully reform, not eliminate, CDA 230 to hold social media platforms accountable for their role in fomenting hate. Reform must prioritize both civil rights and civil liberties. Free speech can be protected while taking care not to cement Big Tech’s monopolistic power by making it too costly for all but the largest platforms to ward off frivolous lawsuits and trolls. Many advocates and legislators have focused on reforming CDA 230 in search of a nonexistent one-stop solution, but it is important to acknowledge that ratcheting back CDA 230 is a single step in a much larger process. Reforming CDA 230 to make platforms liable for unlawful third-party content is unlikely to affect much of the “lawful but awful” hate that saturates the internet because that speech is often protected by the First Amendment in the United States. Thus, the government must also pass laws and undertake other approaches that require regular reporting, increased transparency and independent audits regarding content moderation, algorithms and engagement features.

b. Designate appropriations to increase understanding and mitigate online hate

To adequately address the threat, the government must direct its resources to understanding and mitigating the consequences of hate online. To do so, all levels of government should consider designating funding, if they do not already do so, to ensure that law enforcement personnel are trained to recognize and to effectively investigate criminal online incidents and have the necessary capacity to do that work. Additionally, the federal government has yet to invest meaningfully in examining the connections between online hate speech and hate crimes. Congress should task relevant federal agencies, including the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice, with funding civil society organizations to conduct research, and to catalog and share data with authorities, about those cases in which hateful statements in digital spaces precede and precipitate hate crime. The federal government should also ensure the availability of financial support or incentives for nonprofits, researchers affiliated with universities, and other private sector entities to develop innovative methods of measuring online hate, mitigating harassment in online gaming spaces, and altering product designs to ameliorate hate.

The federal government also possesses the necessary resources and reach to develop educational programming on digital citizenship, the harms of cyberharassment, and accurate identification of disinformation to prevent the spread of extremism. It should leverage its position by funding public awareness campaigns with partner organizations to build resilience against hate online.

c. Strengthen laws against perpetrators of online hate

Hate and harassment exist both on the ground and in online spaces, but our laws have not kept up. Many forms of severe online misconduct are inadequately covered by cybercrime, harassment, stalking, and hate crime laws currently on the books. State and federal lawmakers have an opportunity to lead the fight against online hate and harassment by increasing protections for targets and penalizing perpetrators of online abuse. Legislators can make sure constitutional and comprehensive laws cover cybercrimes such as doxing, swatting, cyberstalking, cyberharassment, non-consensual distribution of intimate imagery, video-teleconferencing, and unlawful and deceptive synthetic media (sometimes called “deep fakes”). One way to achieve this is by improving and passing the Online Safety Modernization Act at the federal level. Appropriations are also necessary, as legislatures and executive branches must resource to the threat.

d. Improve training of law enforcement

Law enforcement is a crucial responder to online hate and harassment, especially when users feel they are in imminent danger. Increasing training and resources for agencies is essential to ensure law enforcement personnel can better help people who have been targeted. Additionally, better training and resources can support more effective investigations and prosecutions for these types of cases. Finally, the training and resources should also include ways in which law enforcement can refer people to non-legal support in the event that online harassment cannot be addressed through legal remedies.

e. Commission research on tools and services to mitigate online hate

Users, especially those who have been or are likely to be targeted, rely on platforms to provide them with tools and services to defend themselves from online hate and harassment. Congress should commission research that summarizes platforms’ available tools to their users to protect themselves. The review process should also assess users’ needs and include a gap analysis of available tools and services.

f. Investigate the impact of product designs and implementations

Much of the emphasis has been on the role of platform policy in addressing hate and harassment on digital social platforms, but government actors do not have a solid understanding of the role of product design. Government agencies must support research into how product design and implementation play a role in amplifying and encouraging the spread of hate, harassment, and extremism and making the content and behavior involved in these activities accessible to the public. Governments should also commission a third-party audit of product systems related to product design as a means to hold technology companies accountable in terms of how or whether they are implementing anti-hate by design to address online abuse.

Addendum

ADL has conducted its Online Hate and Harassment survey in collaboration with YouGov for three consecutive years, releasing a report on those results in 2019, 2020 and 2021. As technology companies continue to provide inadequate data about the prevalence and impact of hate and harassment on social media platforms, we believe tracking yearly trends via this survey is an important means to help the public understand the experience of Americans online.

The following addendum contains several charts that aggregate year over year results from ADL’s Online Hate and Harassment survey where a comparison is possible. All of the charts contain at least two years of data for year over year comparisons, while some contain three years of data for comparison. For the charts where there are only two years of comparison, we are not including the third year due to a change in survey methodology that would make comparisons between the first year of the survey and subsequent years inaccurate.

Endnotes

[i] Includes race or ethnicity, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability

[ii] Kari Paul, “'Four years of propaganda': Trump social media bans come too late, experts say”, The Guardian, January 8, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/07/donald-trump-facebook-social-media-capitol-attack

[iii] COVID Data Tracker, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

[iv] Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May be the Largest Movement in U.S. History”, The New York Times, July 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html

[v] David S. Cloud and Eli Stokols, “Trump is throwing a wrench into what is usually a seamless transfer of power”, Los Angeles Times, January 20, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2021-01-20/trump-disrupts-seamless-transfer-of-power

[vi] BBC, “President Trump calls coronavirus 'kung flu'”, June 24, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-53173436

[vii] “ADL Report: Anti-Asian Hostility Spikes on Twitter After President Trump's COVID Diagnosis”, October 9, 2020,

[viii] “Online Hate Index Report: The Digital Experience of Jewish Lawmakers

https://www.adl.org/online-hate-index-digital-experience-of-jewish-lawmakers

[ix] ADL, “Computational Propaganda and the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election: Antisemitic and Anti-Black Content on Facebook and Telegram”, October 21, 2020, https://www.adl.org/resources/reports/computational-propaganda-and-the-2020-election

[x] Facebook corporate blog post, “Removing Holocaust Denial Content”, October 12, 2020, https://about.fb.com/news/2020/10/removing-holocaust-denial-content/

[xi] https://www.stophateforprofit.org/

[xii] Facebook corporate blog post, “Roy Austin Joins Facebook as VP of Civil Rights”, January 11, 2021, https://about.fb.com/news/2021/01/roy-austin-facebook-vp-civil-rights/

[xiii] Casey Newton and Zoe Schiffer, “What a damning civil rights audit missed about Facebook”, The Verge, July 10, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/interface/2020/7/10/21318718/facebook-civil-rights-audit-critique-size-congress

[xiv] Twitter corporate blog post, “Our approach to blocking links”, July 2020, https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/phishing-spam-and-malware-links

[xv] Oliver Effron, “David Duke has been banned from Twitter”, CNN Business, July 31, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/31/tech/david-duke-twitter-ban/index.html

[xvi] Reddit corporate blog post, “Update to Our Content Policy”, June 29, 2020, https://www.reddit.com/r/announcements/comments/hi3oht/update_to_our_content_policy/

[xvii] Jessica Bursztynsky, “Amazon’s video site Twitch suspends Trump’s channel, citing ‘hateful conduct’”, CNBC, June 29, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/29/amazons-video-site-twitch-bans-trump-for-hateful-conduct.html

[xviii] Twitter corporate blog post, “Permanent suspension of @realDonaldTrump”, January 8, 2021, https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/suspension.html

[xix] Joe Walsh, “YouTube Says ‘Risk Of Violence’ Is Still Too High To Lift Trump’s Ban”, Forbes, March 4, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/joewalsh/2021/03/04/youtube-says-risk-of-violence-is-still-too-high-to-lift-trumps-ban/?sh=647a382177bb

[xx] Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook blog post, January 7, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10112681480907401

[xxi] Jeff Horwitz and Deepa Seetharaman, “Facebook Executives Shut Down Efforts to Make the Site Less Divisive”, The Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-it-encourages-division-top-executives-nixed-solutions-11590507499

[xxii] Sinan Aral, Deb Roy and Soroush Vosoughi, “The spread of true and false news online”, Science, March 9, 2018, Vol. 359, Issue 6380, pp. 1146-1151, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6380/1146

[xxiii] Karen Hao, “How Facebook got addicted to spreading misinformation”, MIT Technology Review, March 11, 2021, https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/03/11/1020600/facebook-responsible-ai-misinformation/

[xxiv] Emily Bell, “Facebook’s Oversight Board plays it safe”, Columbia Journalism Review, December 3, 2020, https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/facebook-oversight-board.php

[xxv] Jack Dorsey, tweet posted on January 13, 2021, 7:16 P.M., https://twitter.com/jack/status/1349510777254756352

Donor Recognition

Anonymous

Anonymous

The Robert Belfer Family

Dr. Georgette Bennett

Catena Foundation

Craig Newmark Philanthropies

The David Tepper Charitable Foundation Inc.

The Grove Foundation

Joyce and Irving Goldman Family Foundation

Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation

Walter & Elise Haas Fund

Luminate

One8 Foundation

John Pritzker Family Fund

Qatalyst Partners

Quadrivium Foundation

Righteous Persons Foundation

Riot Games

Amy and Robert Stavis

Zegar Family Foundation