Introduction

On August 12, 2024, an 18-year-old donned a skull mask, black tactical helmet, gloves and body armor with a prominent sonnenrad patch. Armed with two knives and a hatchet, he stabbed five people at a tea garden near a mosque in Eskisehir, Turkey, leaving two in critical condition. Prior to the attack, the teen also attached a camera to his chest to livestream the stabbings on social media. While Turkish authorities claimed that the attacker, known as “Arda K.” was “influenced by computer games,” an ADL Center on Extremism (COE) investigation found that in addition to authoring a white supremacist manifesto that glorified mass shooters, he also extensively posted extremist and hateful content on Steam, the world’s largest digital PC video game distribution service. Developed by U.S. software corporation Valve, Steam is a storefront for video games and a social networking space for gamers across the globe.

This attack was not the first time that Steam has been linked to the violent and hateful world of extremism. Over the years, ADL and others – including researchers, media outlets, policymakers and governing bodies – have warned about the proliferation of extremist content on the platform.

To understand the scale and nature of hateful and extremist content on Steam, the ADL Center on Extremism (COE) conducted an analysis of public data on Steam Community on an unprecedented, platform-wide scale, analyzing 458+ million profiles, 152+ million profile and group avatar images and 610+ million comments on user profiles and groups.

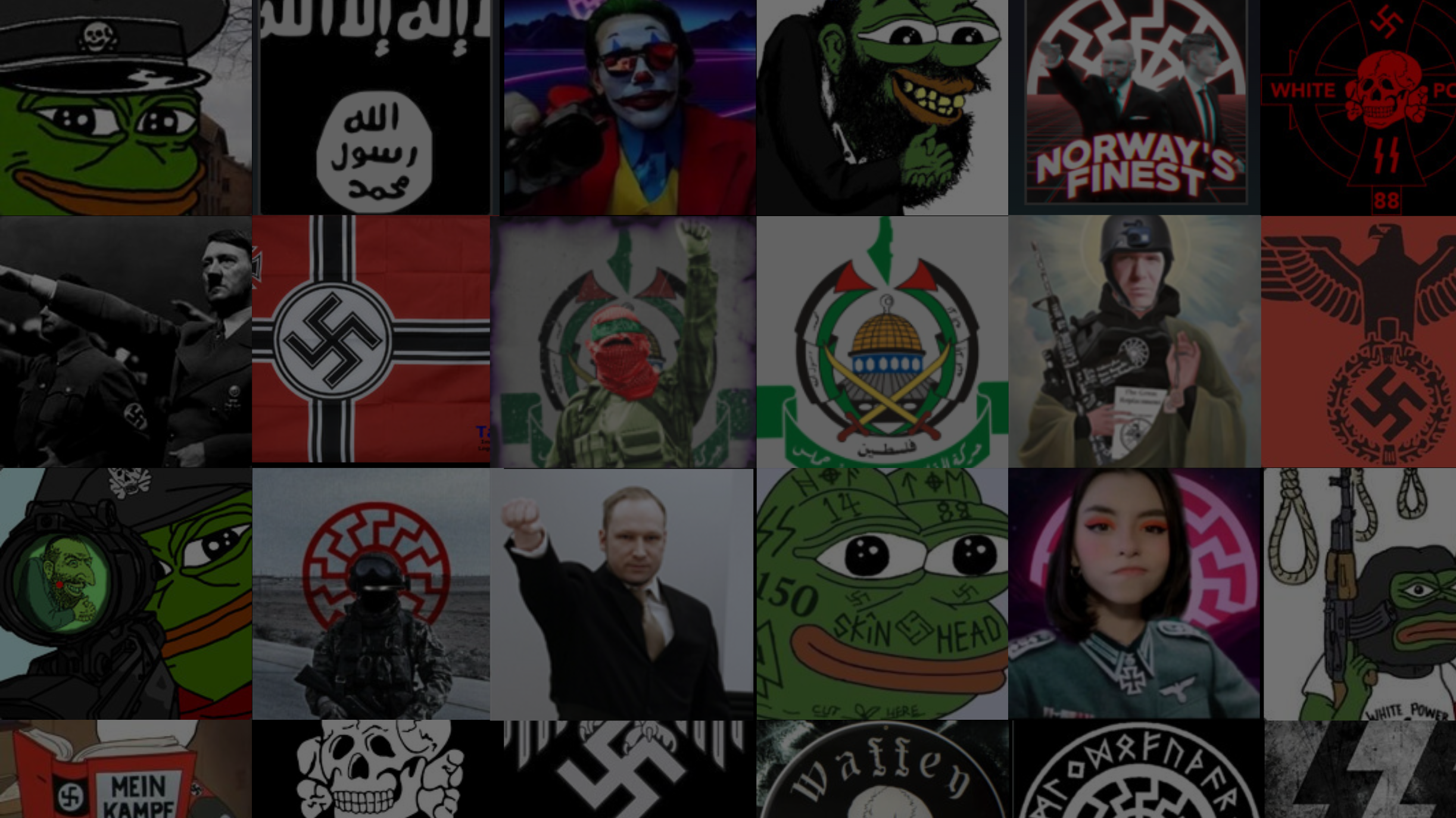

COE found millions of examples of extremist and hateful content – including explicit hate symbols like sonnenrads and “happy merchants,” as well as copypastas (blocks of text that are copied and pasted to form images or long-form writing) shaped into swastikas – on Steam Community, the platform’s social networking space where users can connect, congregate and share content. The clear gaps in Steam’s moderation of this content inflict harm by exposing untold users to hate and harassment, enabling potential radicalization and normalizing hate and extremism in the gaming community. Understanding the extent of extremist and hateful content on the platform is key to fighting the proliferation of hate online.

Key Findings

- Extremist and hateful content – in particular, white supremacist and antisemitic content – is widespread on Steam Community pages. COE identified:

- 1.83 million unique pieces of extremist or hateful content, including explicitly antisemitic symbols like the “happy merchant” and Nazi imagery like the Totenkopf, swastika, sonnenrad and others. This also includes tens of thousands of instances of users expressing support for foreign terrorist organizations like Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Hamas and others.

- 1.5 million unique users and 73,824 groups who used at least one potentially extremist or hateful symbol, copypasta or keyword on the platform.

- Copypastas are a popular method for sharing extremist or hateful content on Steam. COE detected 1.18 million unique instances of potentially extremist and hateful copypastas, 54 percent (634,749) of which were white supremacist and 4.68 percent (55,109) were antisemitic. The most popular copypastas were, by far, variations of swastikas, at 51 percent.

- A significant number of Steam users and group pages use an avatar (profile picture) with potentially extremist or hateful symbols. Multiple users can have the same avatar image. COE identified 827,758 user and group profiles with avatars that contained extremist or hateful symbols. The most popular were Pepe, swastikas, the white supremacist skull or “siege” mask and the Nazi Eagle. COE also found 15,129 profile avatars that contained the flags, emblems or logos of foreign terrorist organizations, the most popular of which was ISIS.

- COE identified 184,622 instances of extremist or hateful keywords on Steam. Of those, 119,018 accounts employed 162,182 extremist keywords in comments or on their profiles. Additionally, 18,352 groups had extremist or hateful keywords on their group profiles. The most used keywords in an extremist or hateful context on Steam Community are “1488,” “shekel” and “white power.”

- COE analysts identified thousands of profiles that glorify violent extremists, like white supremacist mass shooters. These include avatar pictures featuring mass shooters, references to manifestos and stills from livestreamed attacks, like the 2019 Christchurch, New Zealand, shooting. In some cases – like the 18-year-old white supremacist who attacked a café in Turkey in August 2024 – users posting this content on Steam have subsequently committed acts of offline violence.

- While Steam appears to be technically capable of moderating extremist and hateful content on its platform, the spread of extremist content on the platform is due in part to Valve’s highly permissive approach to content policy. In rare notable cases, Steam has selectively removed extremist content, largely based around extremist groups publicized in reporting or in response to governmental pressure. However, this has been largely ad hoc, with Valve failing to systematically address the issue of extremism and hate on the platform.

Background

Platform Overview

Valve’s Steam platform is the world's most popular online gaming marketplace. A 2020 industry-wide survey of game developers found that most respondents (around 60 percent) made at least some of their money selling games on Steam. Almost half (41 percent) generated at least some revenue selling games directly to customers, while a third made between 76 percent and 100 percent of their game revenue on the Steam platform. In 2021, Steam’s annual game sales peaked at over $10 billion, accounting for a significant portion of all PC game sales globally.

Steam Community is an optional social media component of Steam. It is a fully functional social media platform, complete with profiles, which users can customize with text and images; groups, where users participate in threaded discussions; and comments, where people can interact with friends.

Extremism and Steam

Steam’s public-facing content policy includes no mention of hate or extremism. In 2018, following controversy over a game that simulated a school shooting, Valve announced it would allow all games on Steam “except for things that we decide are illegal, or straight up trolling.” This is in sharp contrast to the much more comprehensive policies of other gaming platforms and live service providers like Activision Blizzard and Microsoft. Even Roblox, which Hindenberg Research recently called out for their egregious approach to numerous kinds of heinous content, has an anti-extremism and terrorism policy in place.

Methodology

To understand the scope of extremist content on Steam on a platform-wide scale, COE’s quantitative analysis examined three types of media: extremist symbols (in profile and group avatars), copypasta (in multi-line text fields) and keywords (in short and long text fields). Concurrently, COE analysts conducted in-depth qualitative investigative research into users and groups of interest.

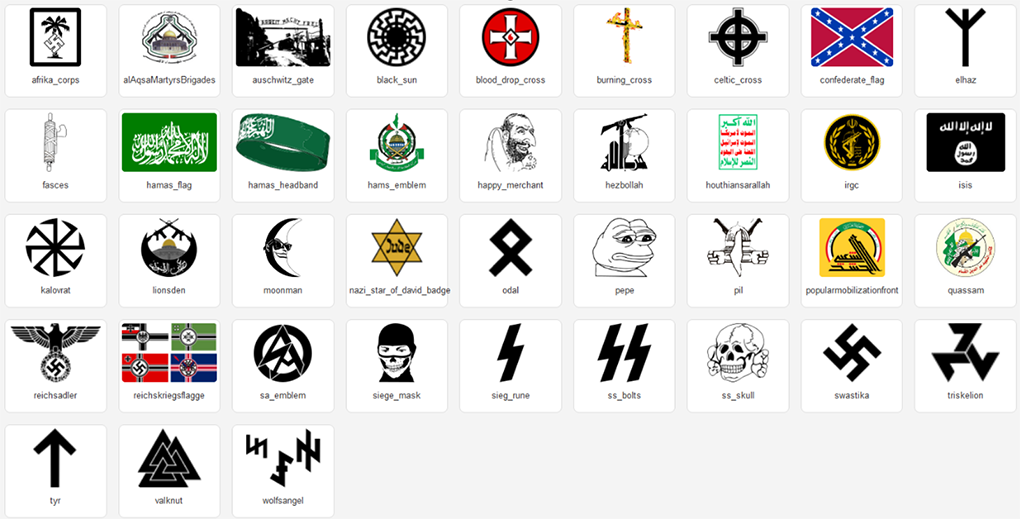

The hate symbol image detection research in this study was conducted using HateVision, a proprietary machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) tool developed by the Center on Extremism. Leveraging cutting-edge computer vision technology, HateVision is trained on a comprehensive dataset of 39 key symbols often used in extremist and antisemitic contexts. This powerful tool rapidly scans and identifies hateful content in images, enabling COE to analyze vast amounts of data and detect hate, extremism and antisemitism with high precision. An exploration of methodology is available at the bottom of this page.

Overall Proliferation of Extremist and Hateful Content

White supremacist, antisemitic and hateful content is widespread on Steam Community pages. Aggregating images, keywords and copypasta content, COE identified 1.83 million unique pieces of potentially extremist or hateful content. 1.5 million unique users and 73,824 groups used at least one potentially extremist or hateful symbol, copypasta or keyword on the platform.

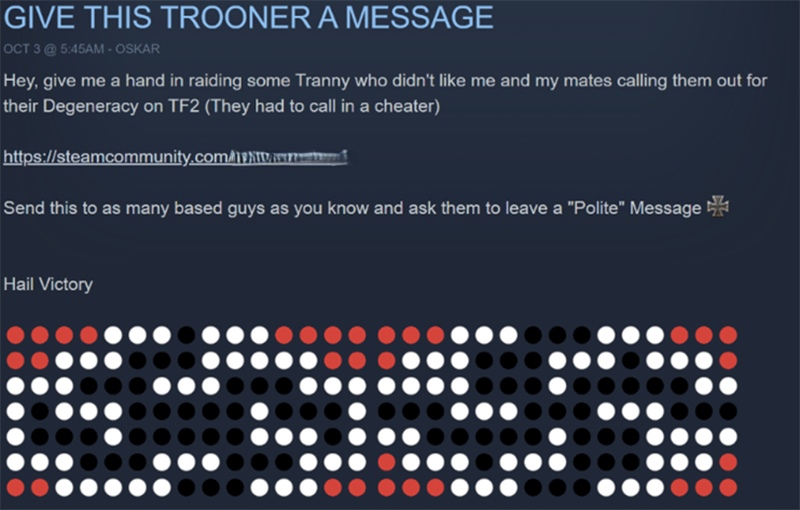

Post on a Steam group page using transphobic slurs, swastika copypastas and the white supremacist phrase, “hail victory.”

Images

Of the approximately 152 million distinct images of Steam profile or group avatars evaluated by HateVision, 493,954 contained potentially extremist symbols. On Steam, multiple users can have the same avatar image. COE found that 827,758 of the approximately 273 million users with custom profile pictures and 57,327 of the around 10.86 million groups with custom profile pictures contained a potentially extremist symbol. Pepe, swastikas, siege masks and the Nazi eagle were the most frequently identified symbols[1].

From left to right: Antisemitic Steam Community avatar with a Nazi-dressed Pepe sniping a happy merchant, suggesting violence against Jews, Steam Community avatar showing Pepe in an S.S. uniform outside of Auschwitz, Antisemitic Steam Community avatar combining the happy merchant meme with Pepe and white supremacist Steam Community avatar depicting Pepe in an S.S. uniform.

Of 493,954 images, HateVision detected 996,808 instances of extremist images on Steam, as multiple symbols can appear within a single image and multiple users can use the same image as their profile avatar. Of the 996,808 detections, Pepe was the most detected symbol, accounting for over 544,267 or 54.6 percent of all symbol detections. The next most common symbols were swastikas (around 90,000, or 9 percent of all detections) and siege masks (over 85,000, or 8.6 percent of detections).

These numbers are likely to be conservative. As discussed in the methodology section of this report, the HateVision model was deliberately trained to optimize precision (the proportion of images the model flags that are actually extremist) rather than recall (the proportion of all extremist images that the model flags). COE also reviewed only publicly available profiles. This means far more profiles likely display extremist symbols than were flagged by the HateVision system.

Group profile with an antisemitic avatar image, displaying the Star of David badge used by the Nazis to identify Jewish people. The Hebrew text reads “Jew” and “Anne Frank, in the attic,” showing clear antisemitic connotations.

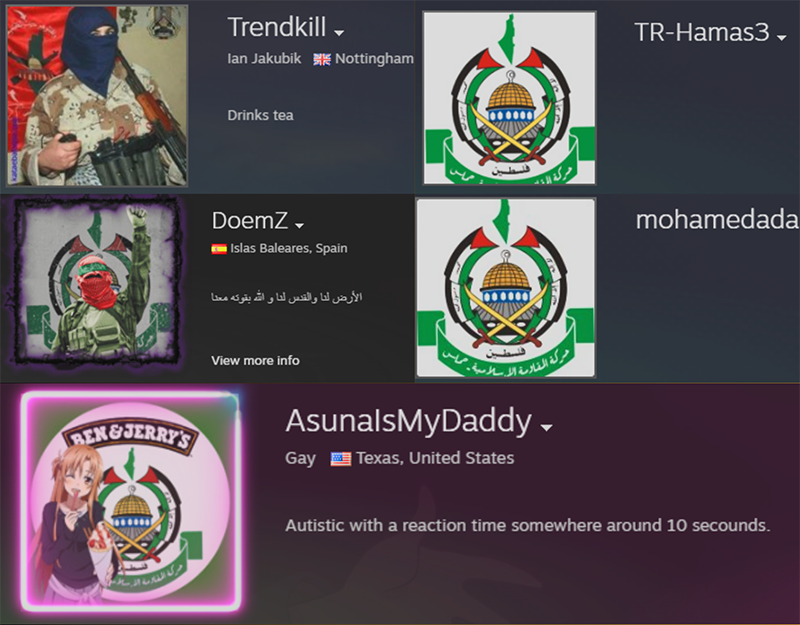

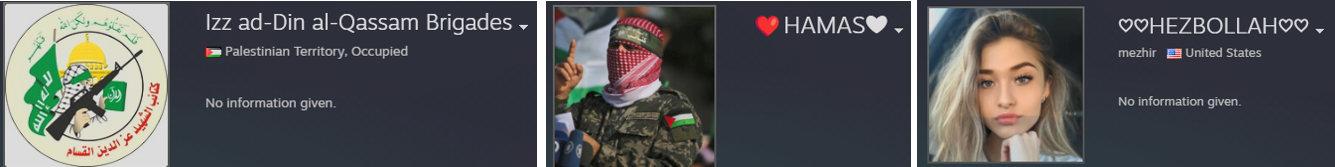

COE also identified tens of thousands of pieces of terrorism-related content on Steam Community, locating 15,129 public accounts with profile pictures containing the logos and flags of foreign terrorist organizations like ISIS, Hezbollah, Al-Qassam Brigades, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), Hamas and others. COE applied the same rigorous effort and attention to identifying terrorism-related content as with white supremacist material, ensuring thorough detection across all forms of extremist content. The number of profiles displaying this type of content via an avatar was lower than the number of profiles elevating white supremacist or Nazi content.

Examples of profile avatars with containing Hamas emblems.

![Examples of the ISIS flag in avatars, with one user named “Ifuckingloveisis [sic]” and another named “isis [sic] enjoyer.”](/sites/default/files/images/2024-11/Steam-Powered-Hate-800-5_0.png)

Examples of the ISIS flag in avatars, with one user named “Ifuckingloveisis [sic]” and another named “isis [sic] enjoyer.”

Copypastas

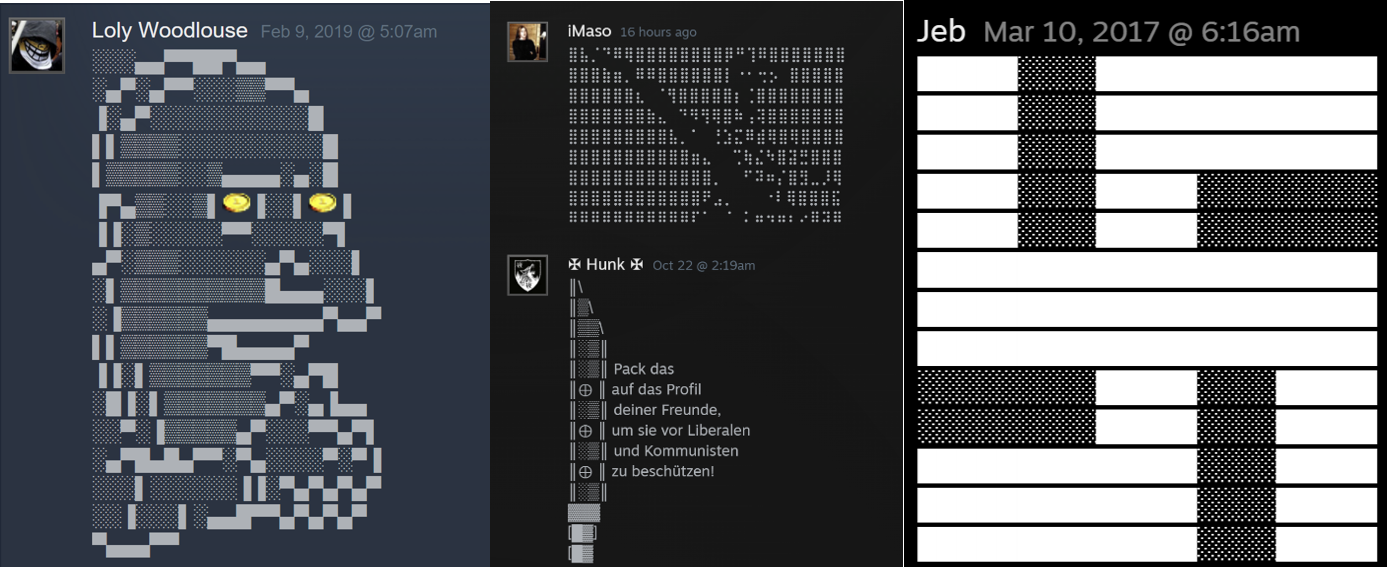

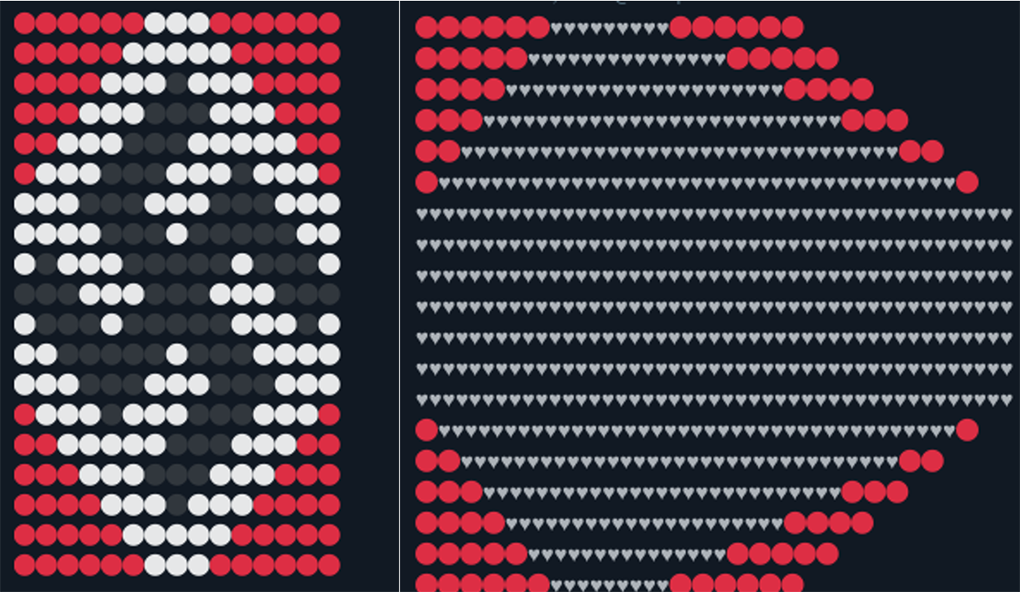

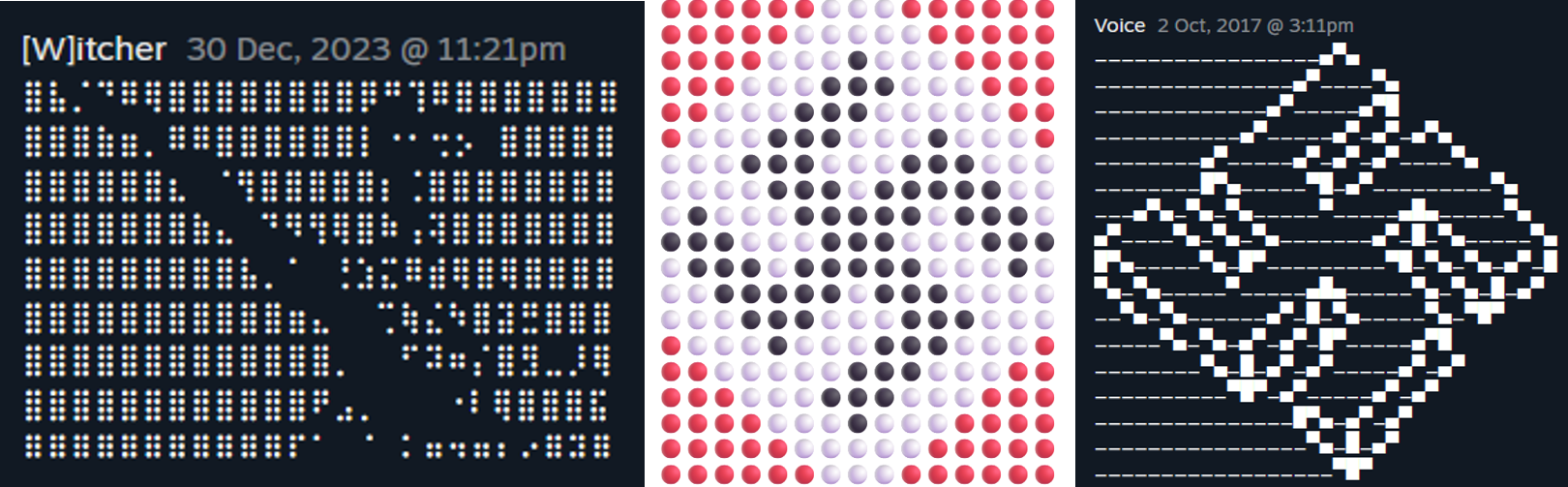

Examples of extremist or hateful copypastas shared on Steam.

After scanning publicly available group comments and summaries and profile comments and summaries for 177 instances of extremist ASCII[2] art, COE detected 1.18 million potentially extremist copypastas, 1.09 million of which were determined to be hateful or extremist with a high degree of confidence. Of the 1.18 million copypastas COE detected, 55,109, or 4.68 percent, were antisemitic and 634,749, or 54 percent, were white supremacist. The most popular copypastas were, by far, iterations of swastikas.

Swastikas, the n-word, and an antisemitic copyapasta involving a knife (shown below) were the most common copypastas on Steam Community.

Examples of the most popular hateful or extremist copypasta images found on Steam.

COE found that 424,439 users posted 808,629 profile comments with extremist copypastas onto 538,092 users' profiles. Most of these users—418,889, or 98.7 percent—posted an extremist copypasta in a profile comment fewer than 10 times. These users posted 88.0 percent of profile comments with extremist copypastas. The most prolific 1.31 percent of copypasta posters, on the other hand, posted a disproportionate 12.6 percent of all comments with extremist copypasta. The outsized impact of this small number of users plainly displays the relative ease with which Valve could address the proliferation of hate and extremism on the platform by targeting these users.

Keywords

COE identified 184,622 instances of extremist or hateful keywords on Steam. 119,018 accounts employed 162,182 extremist keywords in comments or on their profiles. Additionally, 18,352 groups extremist or hateful keywords on their group profiles. The most used keywords on Steam Community in an extremist or hateful context are “1488,” “shekel,” and “white power.”

Of these 184,622 detections, 33,506 keywords, or 18.6 percent, were antisemitic and 101,288 keywords, or 54.8 percent of all detections, were white supremacist.

The most common keyword was 1488, a white supremacist shorthand for the “14 words” (“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children”) and the abbreviation “HH”—the 8th letter of the alphabet repeated twice—which stands for “Heil Hitler.” COE detected 60,721 instances of 1488, which was 32.9 percent of all extremist keyword detections.

Most popular keywords. Note that semantically similar keywords are grouped for this visualization. For example, “zog” and “zogbot” are counted as instances of the concept “zog” and “juden” and “judin” are grouped as “juden.”

Antisemitic groups detected via keyword queries on Steam Community.

COE also detected thousands of users with profile names dedicated to foreign terrorist organizations, like ISIS, Hamas, Hezbollah and others, as well as the names of known terrorists.

Examples of profile names dedicated to terrorist organizations.

Violent Extremist Content

Through qualitative investigative research, COE analysts identified thousands of profiles glorifying violent extremists. These profiles include avatar pictures featuring mass shooters, references to manifestos and stills from livestreamed attacks. In at least two cases, users posting this content on Steam have subsequently committed acts of offline violence.

Profile Pictures and Names

COE found that many users glorify violent extremists, particularly white supremacist mass shooters, using profile avatars depicting killers or referencing them in profiles names.

Brenton Tarrant, who killed 51 people and injured 89 more in a 2019 attack on a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, and Anders Breivik, a Norwegian white supremacist who killed 77 people in 2011, were particularly popular profile avatars. COE investigators located hundreds of accounts with images of Tarrant and Breivik in their profile avatars.

Examples of Steam user avatars depicting Tarrant (left) and Breivik (right).

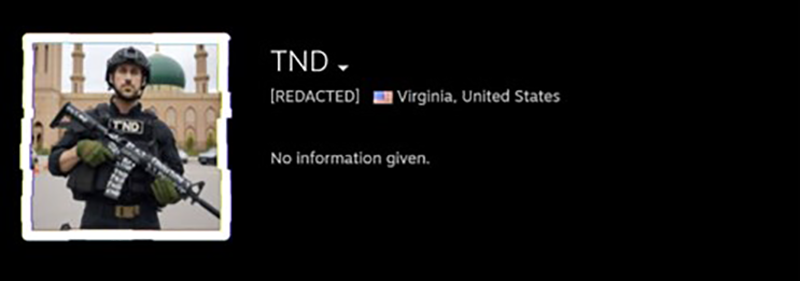

In a particularly disturbing example, one user with a profile name “TND,” referencing a popular white supremacist copypasta meaning “total n****r death,” displayed a profile avatar depicting actor Ryan Gosling as Brenton Tarrant, including a weapon with white script, a helmet and body armor all resembling that which Tarrant used during the attack. Gosling is shown standing outside of a mosque, further referencing Tarrant’s attack.

Steam user TND with an avatar depicting actor Ryan Gosling as Brenton Tarrant.

Hundreds of users used other violent extremists in their avatar images, such as Stephan Balliet, a white supremacist and antisemite who attacked a synagogue in Germany on Yom Kippur in 2019, killing two and injuring two.

Examples of Steam Community avatars depicting Balliet.

Profile names and other customizable text in user profiles also contained thousands of references to violent extremists. Thousands of users named themselves after Tarrant, Breivik and Balliet. Another popular subject for avatars and profile names was Payton Gendron, who attacked the Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York, in 2022.

Showcases

Steam Community profiles also feature a “showcase” section that allows users to post custom content in the form of images. These also proved popular for sharing violent extremist content.

Showcase images showing screenshots from Tarrant’s mass killing, one of which (bottom) includes quotes from his manifesto.

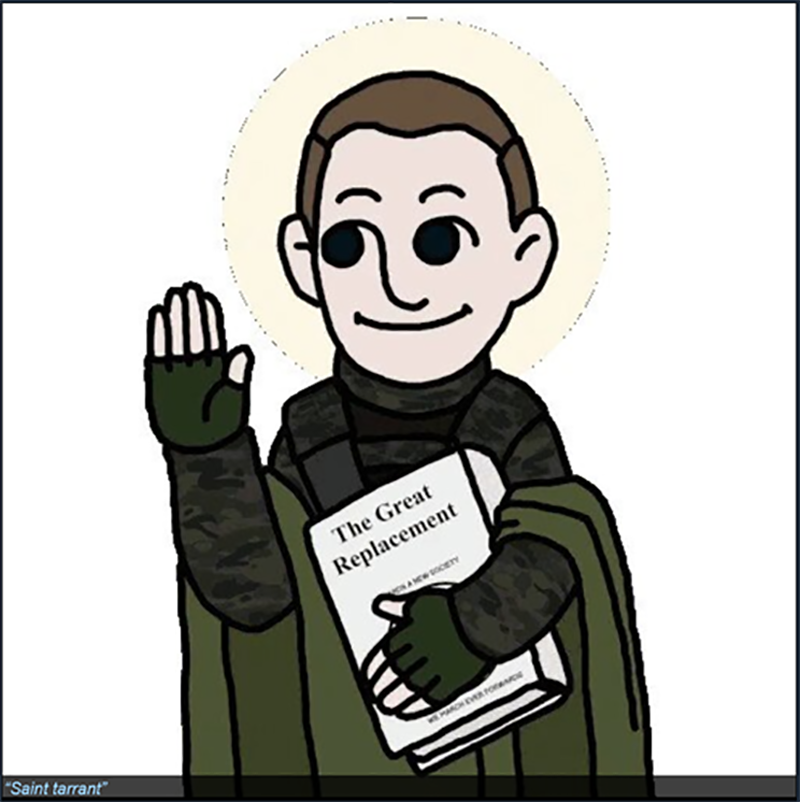

Several users posted screenshots from Tarrant’s livestream of the mosque attack. One user posted to their profile showcase a cartoon depiction of Tarrant holding his manifesto, “The Great Replacement,” like a bible with the caption, “Saint tarrant [sic].” Referring to mass killers as “saints” is common among those who glorify violent white supremacists. The showcase image serves as alternative way of signaling ideology and glorifying Tarrant without directly referencing his act of violence, which may have broader appeal and be less detectable to laypeople.

Showcase image depicting Tarrant as a saint, holding his manifesto like a bible.

Collections and Mods

On Steam Community, members can also publish “collections,” groups of game modifications – commonly called mods – that allow users to alter games or add custom content. COE located many of these dedicated to Tarrant and other violent white supremacists, allowing users to recreate mass shootings in game and otherwise glorify the perpetrators. One user, who named their profile after Tarrant and used an image of the Australian shooter in their avatar, created a collection for the popular game Garry’s Mod called “the Australian Shitposter collection.” The cover image for the collection shows an animated character dressed in the body armor Tarrant wore during the attack, wielding an assault weapon modeled after the one Tarrant used. The image shows the character next to a kebob meat rotisserie, implying the character is killing Muslims as Tarrant did in 2019.

Another user created a collection for Garry’s Mod called the “Brenton Tarrant Pack,” which includes mods that enable users to recreate the Christchurch shooting in the game.

The “Australian Shitposter collection” cover image.

COE also found hundreds of other mods for Garry’s Mod and other games that specifically reference mass shootings. One user alone posted maps – downloadable spaces – for the Christchurch shooting, Columbine, the Tops supermarket shooting and others. Several hundred users celebrated the maps, making comments like, “based,” “sigma map,” “remember lads, subscribe to PewDiePie [a direct reference to Tarrant’s remarks just as he began his attack],” “make synagogue next” and requesting other shootings to be recreated by the modder. The modder also created several detailed models of the weapons and armor used by Tarrant, Gendron, Balliet and several others.

Violent Extremist Content on Steam and Offline Violence: August 2024 Turkey Attack

While the volume of content glorifying violent extremists on Steam is relatively small compared to other extremist and hateful posts on the platform, in one case, a user posting this content on the platform engaged in an act of offline violence.

On August 12, 2024, an 18-year-old man identified by authorities as “Arda K.” conducted a stabbing attack at a café outside of a mosque in Eskisehir, Turkey, injuring five people. A COE investigation found that the attack was fueled by the extremist’s belief in accelerationism and inspired by past mass killers, including white supremacists.

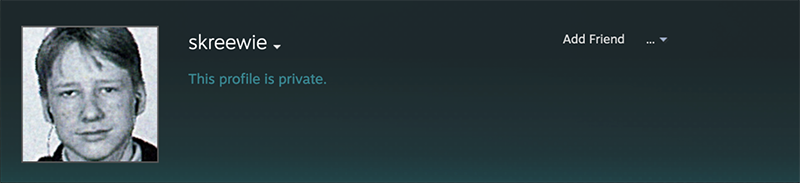

Following the attack, COE identified a Steam Community profile belonging to the attacker with the username “skreewie.” While there is no evidence to suggest that the attacker was directly inspired by extremist content on Steam or that he shared details about his attack on the platform, a review of his account found that prior to the attack (and when his profile was public), he had shared a large amount of extremist content – including using an image of a young Anders Breivik as his avatar – and that he threatened violence on Steam. His apparent radicalization fits what other white supremacists seek to achieve: inspire like-minded people through their violent and hateful content to act in the real world.

The private Steam Community profile COE tied to the Turkey attacker, with a profile avatar image depicting a young Anders Breivik.

Skreewie’s publicly available comments paint a striking portrait of an individual with violent extremist beliefs who, on many occasions, made several direct calls for violence. Since creating his account in 2015, the attacker posted 301 comments on 17 other users' profiles, many of which used explicitly white supremacist accelerationist language. As is common among accelerationists who commit violent attacks, the attacker referred to other mass shooters as “saints,” writing, “Breivik did more to ‘protect and serve’ his people in one afternoon than any police force has in decades... hail saint Breivik.”

He also referenced Pulse nightclub shooter Omar Mateen, who killed 49 people in a 2019 Islamist terrorist attack on a popular gay nightclub, writing, “If Mateen can kill fifty, imagine what you can do.” He favorited a “guide” – a space that, when used as intended, allows Steam members to share tips on games – that consisted of a detailed 5,500-word manual for evading FBI and other government surveillance, suggesting he was interested in the tactical guidance.

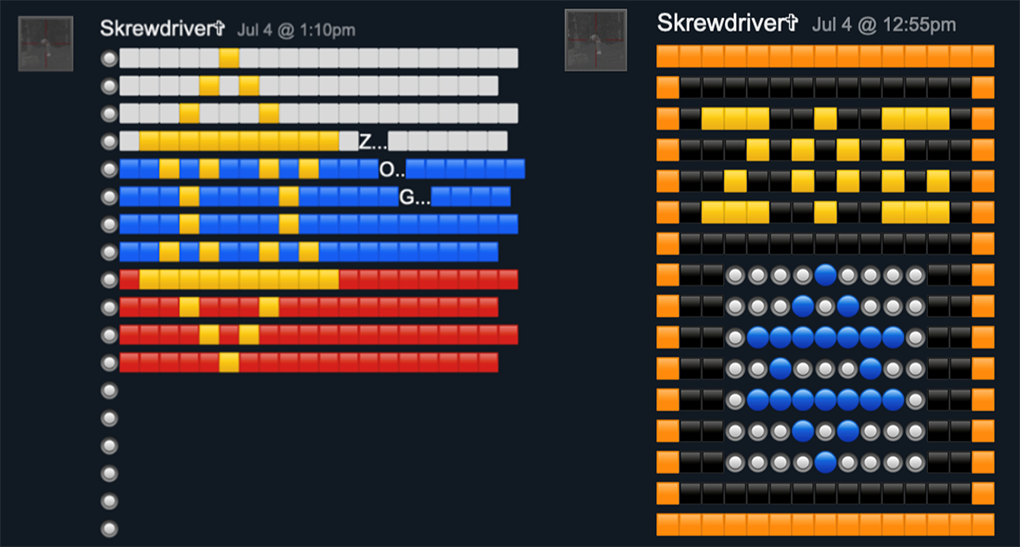

On Steam, the Turkey attacker also posted vitriolic antisemitic comments and copypastas. He made five comments referencing “ZOG,” as well as one mentioning “6 gorillion,” a common white supremacist reference to the approximately six million Jews who were killed during the Holocaust.

Antisemitic “ZOG” copypasta posted by the Turkey attacker to other users’ profiles on Steam Community.

The attacker also created four collections of game modifications. Two of the collections include extremist imagery. The first, a collection the user titled “russia [sic],” has a cover image of a concentration camp gas chamber. Another image associated with the collection shows a 19-year-old Australian man who was arrested in June 2024 for attempting a mass stabbing at the Newcastle Museum after posting a white supremacist manifesto. Another collection features an image of Anders Breivik during his attack in Norway.

![Left: Cover image for the attacker’s Steam collection depicting a Nazi gas chamber used to exterminate Jews during the Holocaust. Center: Image of the 19-year-old Australian who attempted a mass stabbing that the Turkey attacker used in his “russia [sic]” collection. Right: Collection cover image posted to Steam by the Turkey attacker showing Breivik.](/sites/default/files/images/2024-11/steam-powered-hate-800-28-3-1020.png)

Left: Cover image for the attacker’s Steam collection depicting a Nazi gas chamber used to exterminate Jews during the Holocaust. Center: Image of the 19-year-old Australian who attempted a mass stabbing that the Turkey attacker used in his “russia [sic]” collection. Right: Collection cover image posted to Steam by the Turkey attacker showing Breivik.

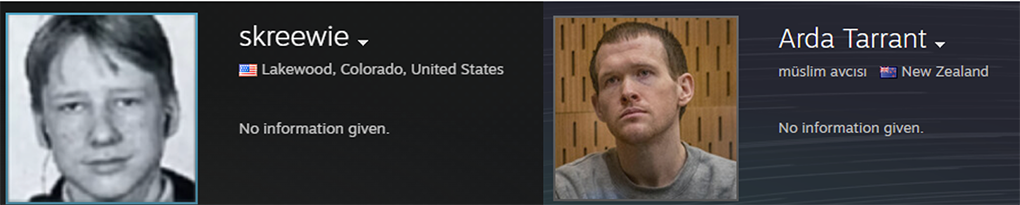

Much in the way that the attacker glorified Breivik, Tarrant, Balliet and others, COE’s review of Steam located several accounts already using the Turkey attacker’s moniker and profile image to honor him.

Profiles honoring the Turkey attacker. Left: A user changed their profile name and avatar to match that used by the Turkey attacker on Steam. Right: A user with a profile name combining the Turkey attacker’s real name with that of Brenton Tarrant.

Content Moderation and Moderation Evasion

The fact that extremist and hateful content is relatively easy to locate on Steam — and in cases like the Turkey attack, where a user posting this kind of content on the platform committed an act of violence — raises questions regarding the efficacy of Steam’s moderation efforts.

In the past, Steam has removed extremist content from its platform. For example, Valve removed specifically mentioned extremist groups on the platform only after they were publicized by journalists. In response to a 2019 complaint by Germany's Media Agency Hamburg/Schleswig-Holstein, Steam removed dozens of pieces of Nazi-related content that violate German law.

A COE analysis of copypastas on Steam also found evidence that Steam attempted to moderate certain extremist content before stopping for unknown reasons. From late 2019 through the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when users in gaming spaces reached an all-time high, the use of several swastika copypastas sharply dropped to near-zero rates. The same swastika copypastas then sharply increased in frequency in September 2020, suggesting that Steam moderated this content for a brief period. There is no observable difference between the variations in copypasta posted prior to November 2019 and those posted after 2020.

Content Moderation Evasion

Independent of Steam’s content policy, which dictates when it moderates or restricts content, COE identified two specific limitations to its approach when it does moderate content: content restrictions do not apply to all user-generated fields and users can choose to disable this and remove keywords from the block list.

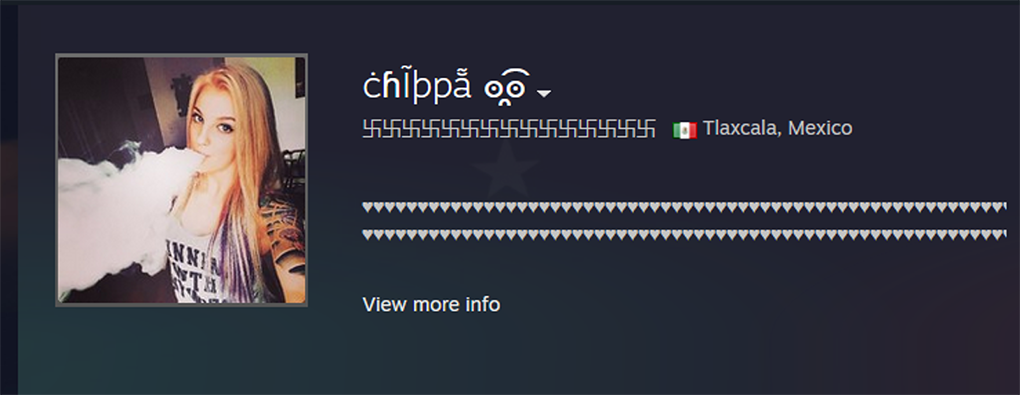

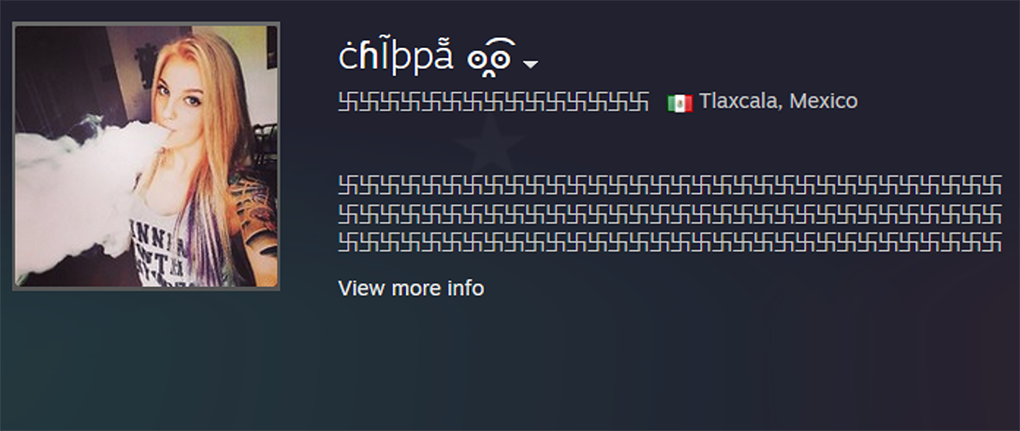

Steam filters content on user summaries and comments. For example, Steam replaces a Unicode swastika symbol, ‘卐', with ‘♥♥♥’. Steam also attempts to censor an emoji-based swastika, shown below. However, users are able to remove words from Steam’s block list in their account settings.

Left: Emoji-based swastika posted to Steam, seen before Steam has attempted to censor the shape. Right: The emoji-based swastika posted to Steam, seen after Steam has filtered the swastika shape.

However, its filters do not apply to all content locations. For example, Steam does not filter content in page titles or users' real name fields: COE detected instances of one specific Unicode swastika in 853 users' real names; this is the exact character that Steam declines to display in users' summaries (COE found only 11 user summaries with the same swastika present; it is unclear why these 11 instances were not filtered).

Keyword filtering does not apply to all fields—the swastikas in the user’s real name field are not filtered, even as Steam detects them in the user’s profile summary.

Steam also permits users to remove keywords from its block list. Below is an example of a profile viewed by a user who has added ‘卐' to their list of allowed words.

Users can remove keywords from the block list—the viewing user has added ‘卐' to the list of allowed words; the swastikas are now visible in the user’s profile summary.

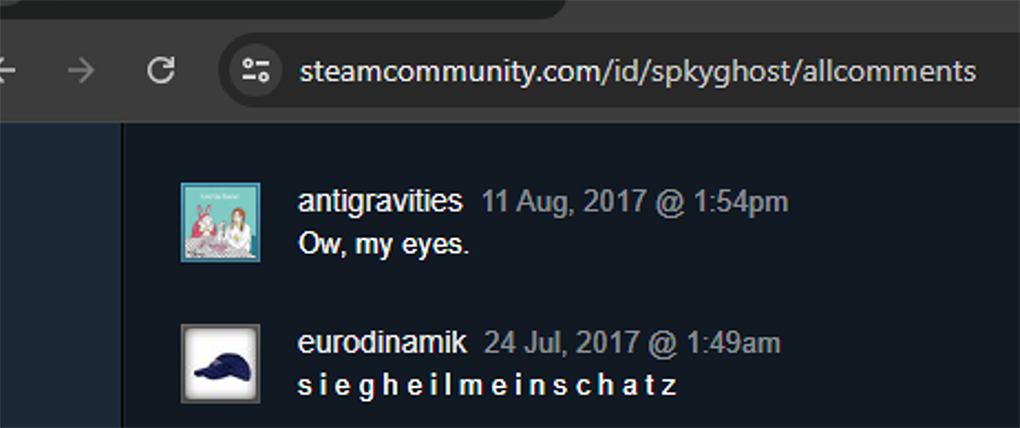

Steam’s keyword detection is also easy to evade. Users alter words and ASCII art, avoiding exact matches to extremist search terms. For example, the user below separated the letters in the expression ‘sieg heil’ with spaces to avoid detection.

Keyword detection is easy to evade—a user evades Steam’s content detection system (which alters ‘sieg heil’) by adding spaces between each letter.

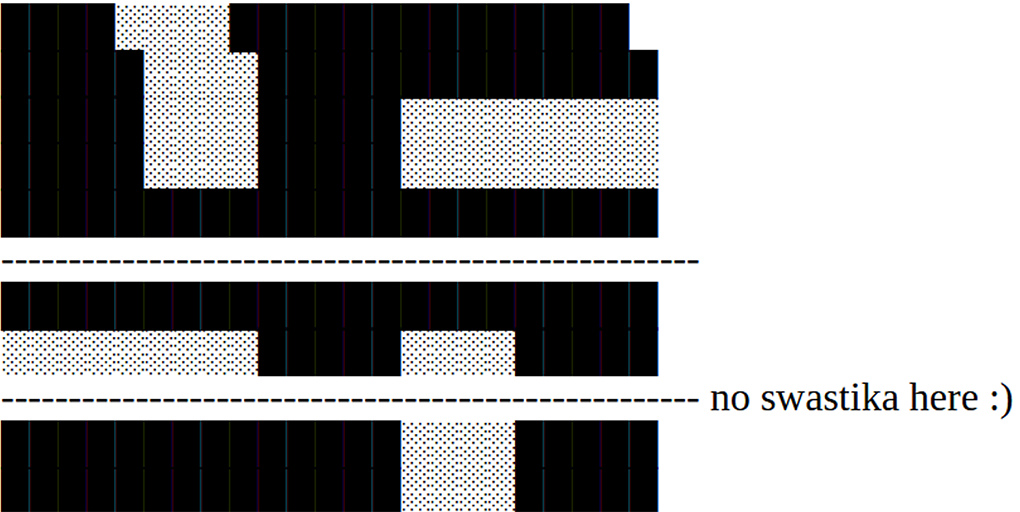

In the image below, a user added lines of dashes to a swastika copypasta to avoid censorship, even writing, “no swastika here :).”

An ASCII art swastika posted on Steam; it has been altered, seemingly with the intent to evade detection.

Recommendations

For Valve

As ADL has said previously, Valve needs to make significant changes to their approach to platform governance both in terms of policy and practice to address the ways in which hate and extremism have proliferated on the Steam platform.

We urge Valve to:

- Adopt Policies Prohibiting Extremism. Currently there is no policy on Steam that prohibits the presence of known extremists, extremist recruitment, the celebration of extremist groups and movements or even the expression of the hateful ideologies that animate extremists. While the game industry is in general behind social media in addressing the abuse of their products by extremist actors, we have seen some progress in the last year. ADL reviewed the recent progress and wrote about three current models for game companies to potentially implement anti-extremism policies.

- Adopt Policies Prohibiting Hate. Steam must have clear policies that address hate and clearly define consequences for violations. Moreover, their platform policies must state that the platform will not tolerate hateful content or behavior based on protected characteristics (race, ethnicity religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin). Most every major social media and gaming company has a policy prohibiting this kind of content—it is time that Valve followed suit.

- Enforce Policies Accurately at Scale. Valve needs to take greater responsibility in enforcing their policies on Steam, once expanded, and do so accurately at scale. They need to utilize both a user flagging and complaint process along with a proactive, swift and continuous process to address hateful content using a mix of artificial intelligence and human monitors who are fluent in the relevant language and knowledgeable about the social and cultural context of the relevant community. Valve should work with trusted industry partners and extremism experts, such as ADL, to ensure these policies’ effective design and implementation across their platforms.

- Audit and Red Team Content Moderation Practices to Close Loopholes. The loopholes to evade content moderation on Steam listed above are likely only a few of many ways bad actors are finding to evade detection and enforcement. In addition to closing those specific loopholes, Valve should undertake a large-scale audit of how bad actors are avoiding detection at present and undertake a company-wide Red Teaming effort to simulate additional ways bad actors might abuse the platform and take learnings from both exercises to improve content moderation on Steam.

- Engage with Civil Society, Academics and Researchers. In establishing and updating their policies, Valve should consult regularly with civil society groups, academics and researchers from a broad cross section of positions, including civil rights and civil liberties groups, and especially seek out and use their advice and expertise to shape platform policies that may impact the experience of vulnerable and marginalized groups.

For Policymakers

As ADL has stated previously, policymakers must demonstrate their commitment to disrupting hate and harassment in online multiplayer games. While government is necessarily focused on the dangers posed by social media and AI, policymakers must also pay attention to the immediate threats pervasive in online gaming environments. ADL recommends different stakeholder groups take the following steps to play an active role in promoting online safety and mitigating the risk of these dangers and their impact on users:

- Prioritize transparency legislation in digital spaces and include online multiplayer games. States are beginning to introduce, and some are successfully passing, legislation to promote transparency about content policies and enforcement on major social media platforms. Legislators at the federal level must prioritize the passage of equivalent transparency legislation and include specific measures for online gaming companies. Game-specific transparency laws will ensure that users and the public can better understand how gaming companies are enforcing their policies and promoting user safety.

- Enhance access to justice for victims of online abuse. Hate and harassment exist online and offline alike, but our laws have not kept up with increasing and worsening forms of digital abuse. Many forms of severe online misconduct, such as doxing and swatting, currently fall under the remit of extremely generalized cyber-harassment and stalking laws. These laws often fall short of securing recourse for victims of these severe forms of online abuse. Policymakers must introduce and pass legislation that holds perpetrators of severe online abuse accountable for their offenses at both the state and federal levels. ADL’s Backspace Hate initiative works to bridge these legal gaps and has had numerous successes, especially at the state level.

- Establish a National Gaming Safety Task Force. As hate, harassment and extremism pose an increasing threat to safety in online gaming spaces, federal administrations should establish and resource a national gaming safety task force dedicated to combating this pervasive issue. As with task forces dedicated to addressing doxing and swatting, this group could promote multistakeholder approaches to keeping online gaming spaces safe for all users.

- Resource research efforts. Securing federal funding that enables independent researchers and civil society to better analyze and disseminate findings on abuse is vitally important in the online multiplayer gaming landscape. These findings should further research-based policy approaches to addressing hate in online gaming.

Full Methodology

Image Detection

The hate symbol image detection research in this study was conducted using HateVision, a proprietary computer vison AI model developed by the Center on Extremism. Manually reviewing the 152.2 million group and profile avatar images collected from Steam was not feasible. Instead, to find extremist symbols in user and group profile images, COE trained a cutting-edge hate symbol detection machine learning model, to detect 39 different symbols pulled from COE’s Hate on Display hate symbols database. There are some symbols, like caricatures and faces, that are symbols of hate but that were not detectable using our approach. See Appendix III: HateVision Limitations for a discussion of these symbols.

Potentially white supremacist, antisemitic and extremist symbols HateVision is trained to detect

Because some of the symbols included in this analysis are also used in non-extremist contexts or are visually similar to non-extremist symbols, we sought to prevent false positives by training only on extremist instances of these symbols. See Appendix III: Labeling Procedure for more information on how we distinguished between extremist and non-extremist instances of these symbols.

After training the HateVision on 65,954 instances of these symbols, the model identified 78.7% of extremist symbols in the test dataset (recall), and 97.1% of the symbols it classified as extremist were actually extremist (precision). We prioritized precision to minimize false positives, ensuring the model does not mistakenly label benign symbols as extremist or hateful. However, this approach likely leads to an undercounting of extremist instances, as some true instances may not be captured due to the focus on precision over recall.

Precision is the proportion of symbols the model classified as extremist that actually contain that symbol. Recall is the proportion of total extremist symbols the model identified. In fine-tuning this model, we prioritized precision over recall to minimize the frequency of false positives. mAP is mean Average Precision, which considers both precision and recall. mAP50 considers clear-cut detections, while mAP50-95 also includes edge-case detections.

As a second step to ensure HateVision accurately detected extremist and hateful symbols, COE randomly sampled 1,100 of the 493,954 images the model identified as containing extremist or hateful symbols. The sample size of 1,100 was determined through a statistical sample size calculation, providing a 3% margin of error at a 95% confidence level. Manual inspection showed that the model correctly classified 1,081 of the 1,100 randomly sampled images and incorrectly identified the remaining 19 images as containing a symbol when they did not (false positives). Based on this representative random sample of images HateVision detected as containing extremist symbols, HateVision’s precision in detecting hate symbols was 98.2% with a margin of error of 3% at a 95% confidence level. We are highly confident HateVision performs robustly on Steam Community profile images and that the extremist symbol detections we report are accurate.

Copypasta Detection

Steam Community users also post copy-and-pasted text-based content known as copypasta. There are two types of copypasta, ASCII art and natural language copypasta. Unlike other social media platforms, Steam Community does not permit users to upload images to text fields like comments. Instead, users create text-based visual art to long-form text fields like comments and user and group summaries. This art may be composed of alphanumeric characters, other symbols, or emojis; for simplicity, we refer to these varieties of these text-based images as ASCII art. Users also post natural language memes or messages that are clearly copy-and-pasted from other sources; these copypasta are not visual.

We scanned over 610 million public comments, which were posted by over 40 million users and are displayed on over 41 million user profiles and 2 million groups. We provide several examples of detected extremist ASCII art and natural language copypasta below.

Examples of Examples of extremist ASCII art detected on Steam Community.

We scanned profile comments and summaries for 177 examples of extremist ASCII art. Because users may inadvertently (during the copy-and-paste process) or intentionally (to evade detection) alter copypasta, we used a fuzzy-matching algorithm to detect exact and highly similar instances of copypasta. The fuzzy-matching algorithm introduces a risk of false positives—that is, we risked mistakenly identifying non-extremist text as extremist copypasta. We took two steps to minimize this risk. First, we used a conservative matching logic which is likely to produce far more false negatives (missed identifications of actual extremist copypasta) than false positives (mistaken extremist identifications of non-extremist text). We also randomly sampled the results of our detection process to visually inspect them for false positives, finding no false positives. Because most examples we detected are exact duplicates of one another, we were able to visually inspect over 90% of the examples our detection system identified as extremist by examining only distinct examples.

Keyword Detection

Extremist content also appears in text; a user might include the words “h1tl3r” or “klux” in a comment or in their username. We constructed a list of 236 search terms by exploring data, adding terms from ADL’s Glossary of Hate, and the input of Center on Extremism subject matter experts.

Detecting hateful keywords is not just a matter of searching for a word in text—the meaning of potentially hateful keywords is highly context-dependent. For example, a group summary might use the number “1488” to communicate white supremacist sentiment; “1488” is often used to represent the 14 Words (“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.") and the 8th letter of the alphabet (HH, or “Heil Hitler”). However, a group’s use of the number “1488” does not independently indicate its ideology; it could be part of a longer number.

We considered any detection of slurs to be true positives. But most keywords, even when properly detected, are used in a variety of contexts. A user might mention ‘auschwitz’ with benign historical intentions, or with the intention of questioning or undermining facts about the Holocaust. For these keywords, we also considered context. In long-form fields, such as comments and user summaries, we considered candidate matches to be true positives only when the user expressed support for the concept (in the case of an extremist or hateful individual or organization) or criticism for the group (in the case of ‘jevvs [sic]’, for example). In short-form text fields, like usernames, we considered any uncritical use of keywords to be true positives (because calling one’s profile ‘himmler’ implies support for the individual).

To prevent false positives, or detection of extremist keywords used in non-extremist contexts, we repeatedly adjusted the matching logic for each keyword until we eliminated false positives from our results. For keywords with fewer than 10,000 detections, we reviewed each detection for false positives; for keywords with greater than 10,000 detections, we repeatedly randomly sampled the detections, ultimately reviewing at least 10,000 results for all keywords. In the case of the keyword “1488,” our matching logic ultimately excluded all instances in which “1488” appeared next to other digits. After multiple iterations, we removed 33 keywords that returned a significant amount of noise, resulting in a final set of 203 keywords.

We ultimately searched for 203 extremist or hateful keywords in multiple user-defined text fields, including users' usernames, real names, summaries, and vanity URLs; groups' names, tags, summaries, and vanity URLs; and profile and group comments.

Dataset

To better understand the full scope of extremism on the platform, COE collected information on all public profiles, friendships, groups, group memberships, and comments through the middle of 2024. The dataset we created is far-reaching; it includes over 458 million profiles, over 152 million images, and over 30 million groups.

COE collected the data in two stages. In late 2023, we collected information on all public profiles, profile comments, groups and group comments created up until the end of 2023. In summer 2024, we updated our data to include profiles, profile comments, groups and group comments created between January 1, 2024, and July 25, 2024. Our data collection covers all publicly available content on the platform at the time we collected the data, reaching back to the earliest retrievable data for each section. This includes user profiles dating back to September 2003, profile comments from April 2009, and groups created from August 2007, reflecting the platform’s gradual rollout of features and capturing its entire publicly accessible history. We believe our dataset to be a comprehensive snapshot of every publicly visible user, group, profile comment and group comment on Steam Community at the time of data collection. Below, we describe what information we did and did not collect.

See Appendix I: Approach to Data Collection for a more detailed explanation of our data collection process.

COE collected descriptive information about each Steam Community user, including their profile pictures, usernames, friendships, and profile summaries to the extent they were publicly available.

An active user’s profile, with a summary, showcase, badges, and groups.

At the time of data collection, Steam Community had 458.32 million users. Of these, 418.4 million were public profiles and 39.68 million were private profiles (even if a profile was private, there was certain related information that was publicly available).

Many of Steam Community’s 458.32 million users have not customized their accounts extensively. Only 7.4% of public profiles have a summary, Steam Community’s equivalent of a social media bio. 41.8% of profiles use Steam community’s default profile picture, making it the most common avatar on Steam, present on 191.2 million profiles.

Most Steam Community users are also not particularly active. One proxy for activity is player level, which users can increase by activities such as buying games or collecting trading cards while playing games on Steam. Among the 91.69% of Steam Community users who publicize their level, the average level is 2.8 and the median level is 0.0 (the maximum level observed was 5,001). Our detections should be interpreted with this context in mind.

Defining Extremist Content in the Context of Steam Community

We scanned content on Steam Community for 203 keywords (down from initial 236), 177 ASCII art examples, and 39 symbols. Some of these, like the “Happy Merchant” meme, are antisemitic or otherwise extremist or hateful in all cases. The meaning of others, like some of the runes we detected, vary depending on context.

Because we were unable to manually review the 1.83 million fields we flagged across all three detection methods, it was instead necessary to assign 1) thematic descriptions and 2) signal strengths to each keyword, copypasta, and symbol. We separated each into one of 8 categories: antisemitic, Nazi or white supremacist, other hate (which included smaller quantities of anti-Black, homophobic, incel, and anti-Muslim content), content related to 9/11 conspiracies, Pepe content and a miscellaneous category. In cases where content spanned multiple categories, we assigned it to the most precise classification available based on HateVision inference results. For instance, while a Holocaust-themed copypasta could be broadly labeled as Nazi or white supremacist, we categorized it as antisemitic due to its specific targeting of Jewish people.

We also classified the signal strength of each keyword, copypasta, and symbol. Signal strength is an indication of how likely a given example is to be used in an extremist context. We assigned one of three tiers, low, medium, or high, to each example. This classification is qualitative; it is based on ADL’s prior reporting on symbols and other content, not a quantitative review of detected examples. Below, we provide an example of a symbol or copypasta with each signal strength.

Unless otherwise specified, in this report we use specific language to describe specific categories of content:

- “Extremist” or “hateful”—Examples with high signal strength belonging to one of the following categories: antisemitic, Nazi or white supremacist, terrorist, or other hate content (which includes homophobic, anti-Black, anti-Muslim, and incel content).

- “Potentially extremist” or “potentially hateful”—Examples with any signal strength belonging to any of the categories we detected.

Appendices

Appendix I: Approach to Data Collection

In 2024, the ADL Center on Extremism (COE) conducted an exhaustive data collection of all publicly visible users and groups on the Steam Community. This platform-wide effort captured the entirety of publicly available profiles, groups and associated content, and only the profiles, groups, and associated content that were publicly available at the time of data collection. The dataset includes over 458.32 million user profiles, 152.2 million profile and group avatar images, and 610.6 million comments. We believe our study to be the most comprehensive snapshot of all Steam Community users and groups to date. Our approach was designed to ensure that no publicly accessible data was overlooked. This thorough dataset forms the basis for our analysis of extremist and hateful content on the platform.

Appendix II: Data Collection Limitations

Due to the vast scale of Steam’s data, we focused on collecting key data fields rather than capturing every publicly available detail for all users and groups. This approach allowed us to prioritize the most relevant information for our research while still ensuring comprehensive coverage of the platform. Below, we detail some of the data we did not collect or analyze where we know extremist content to exist:

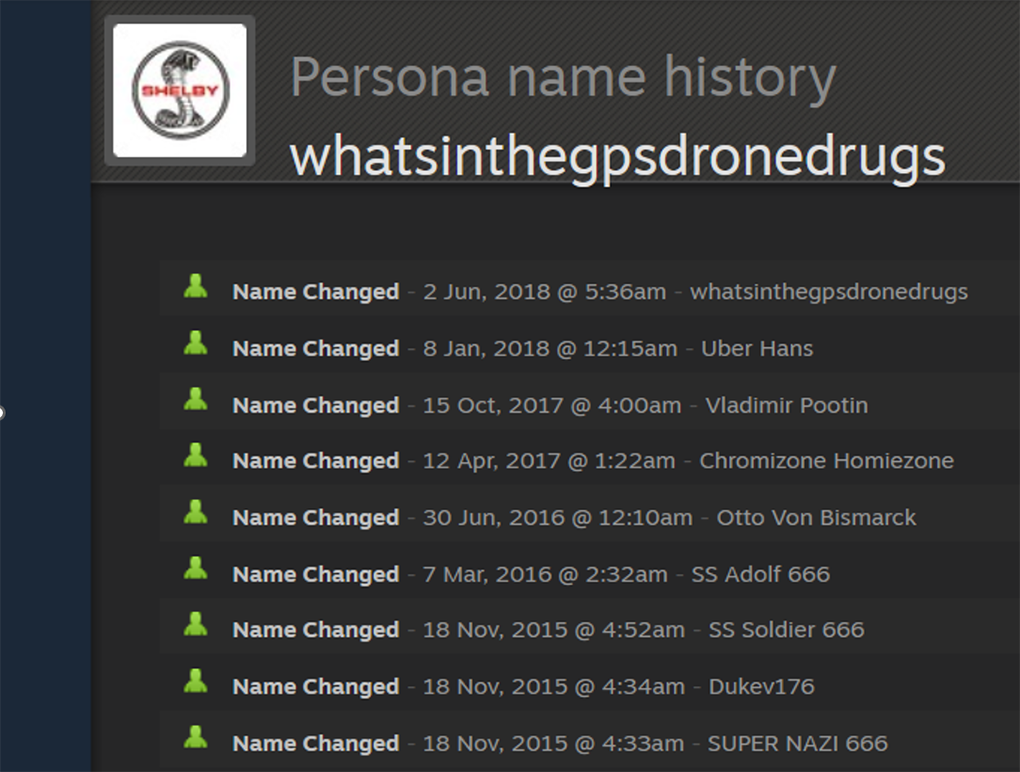

- Name history—Steam Community displays users' former usernames on a separate page from their account if a user does not clear the name history. We did not analyze name history for extremist signals, although we know these pages contain evidence of extremist activity, as shown below.

A user’s name history shows a user’s past extremist persona names, even though their current name is not extremist.

- Item showcases— While we did collect information on item showcases on users' public profiles, we did not analyze the images contained within them. We have observed users spell out slurs and other hateful content using special items; these images can also contain extremist symbols.

Item showcase containing a swastika.

- Game-specific emoticons—Some games offer users custom emoticons as a reward or perk; COE found that the use of some of these may signal extremist beliefs, especially when combined with other pieces of extremist or hateful content.

An emoticon similar to the sieg rune, used as a symbol of the Nazi SS.

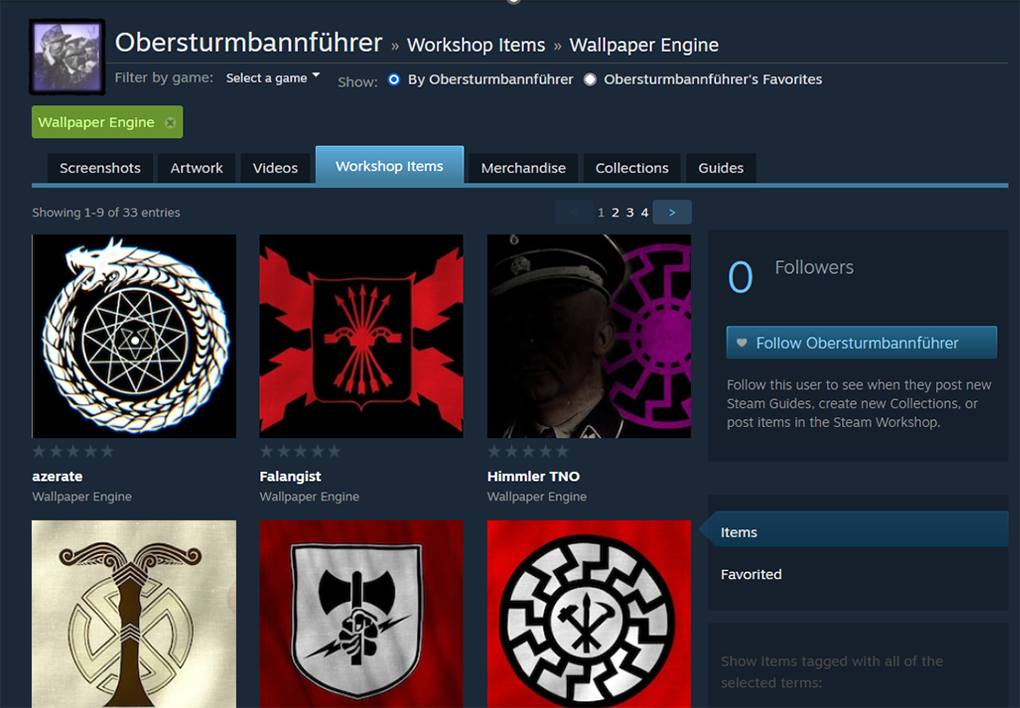

- Workshop items—Steam Community enables users to design and share in-game content (like clothing and equipment) through its Steam Workshop feature. We did not analyze user-created Workshop items, because to doing so would have required owning each game.

Several extremist symbols in a user’s Steam Workshop items.

Steam Community is a complex platform; there are many other fields we did not collect data from, including screenshots, artworks, reviews, or game modifications, commonly referred to as mods. While we encountered extremist messages in some of this content, we did not systematically retrieve or scan them at scale as the hateful and extremist content we came across in these fields was sporadic. We also did not include data that was not publicly available.

Appendix III: HateVision Limitations

In this report, we used HateVision, a cutting-edge hate symbol detection AI model COE trained to detect potentially hateful and extremist symbols in images on Steam Community. We used the HateVision to detect potentially hateful and extremist symbols in hundreds of thousands of images. Based on model performance metrics and our thorough evaluation using random samples, we consider HateVision to be highly reliable in detecting the 39 symbols included in this study. There are, however, several types of symbols we were unable to detect with a hate symbol detection approach:

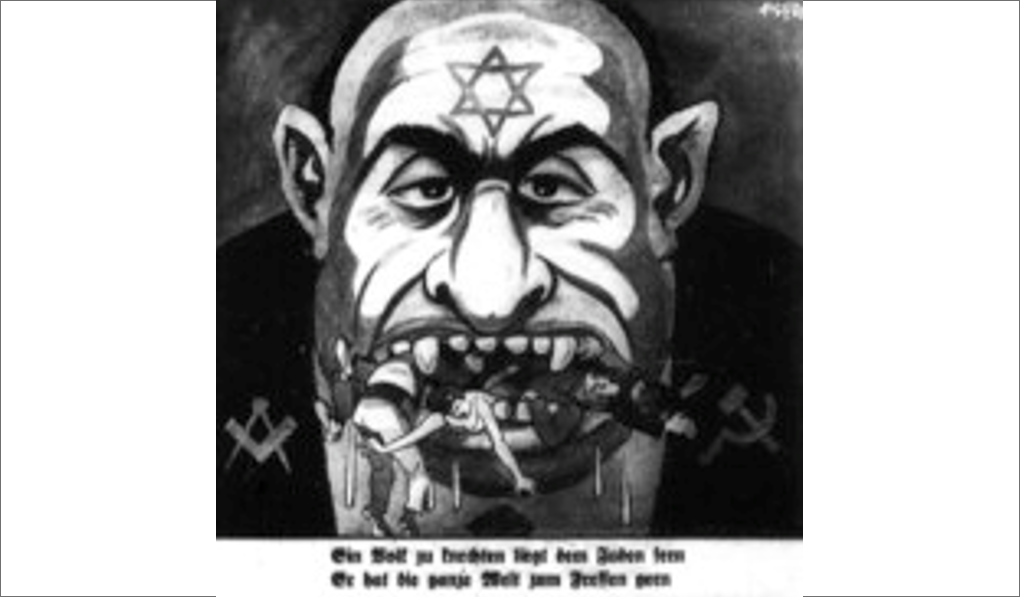

- Complex symbols and caricatures—Users often express ideology through complex images; many otherwise innocuous symbols can be hateful in a specific context. The HateVision AI model described above is unable to consider context, so we only sought to detect symbols that could be reliably classified as extremist in most instances. This means there are likely to be many instances of hateful imagery we did not detect. For example, consider the antisemitic profile image below that contains a Star of David. It was not possible to classify this image as hateful using our HateVision model because many instances of the Star of David are benign; it is the rest of the image that makes the star’s use hateful.

A user’s profile image contains antisemitic imagery not detected by our HateVision system.

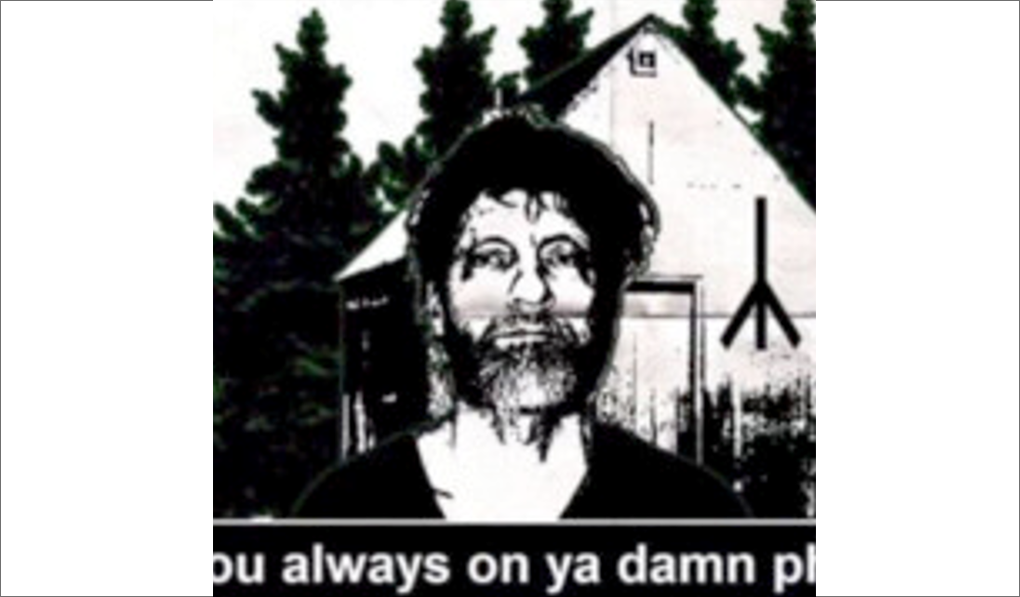

- Faces—Certain individuals (like the mass shooters discussed in a previous section of this report) are symbols of hate and extremism. We did not use facial recognition systems to detect specific people in images.

Ted Kaczynski, a violent extremist, in a Steam Community profile image. Our HateVision model did not detect faces.

[1] For COE’s investigation of Steam, a wide variety of symbols were chosen to better understand the makeup of the extremist landscape. Some symbols, like the sonnenrad and Totenkopf, are explicitly extremist, while others, like Pepe, runes and the kolovrat, are often used by extremists, but their use alone does not signal extremist ideologies.

[2] ASCII (or American Standard Code for Information Interchange) art refers to images made from individual text characters to form a larger image.